Though it is my most prized possession, here’s why I will be leaving my copy of the Divine Comedy behind.

On my training walk today, I experimented with carrying in my rucksack the contents I’ve been carefully curating for the Cammino di Dante.

It includes: a fistful of Compeed blister plasters, a bamboo toothbrush with the end sawed off (thanks Jess for that top tip), two changes of clothes, four pairs of socks and knickers, a solar powered power pack and my laptop. My indulgences include some Ayurvedic balm from Sri Lanka and a collapsible hairbrush.

I always fancied that if I was invited onto the BBC programme Desert Island Discs, I’d take some essential oils with me as my luxury item because smell has a huge Proustian impact on my disposition. It’s enough to sniff some Rose Herbal Essences shampoo and I’m back in Calcutta showering away a difficult day spent with street children at the age of 18.

The Ayurvedic balm, meanwhile, reminds me of turquoise waters and golden sands and the month I spent training to be a yoga teacher in Sri Lanka last year. The sense of peace that comes with the inhale and exhale of a perfectly realized ‘cat-cow’. I figure I’ll need some of that as I walk, not to mention the healing properties it will grant to aching limbs.

When one of my favourite journalists, Lyse Doucet, the BBC Middle East war correspondent, featured on Desert Island Discs she also took essential oils as her luxury item. ‘Cool,’ I thought. I have something in common with Lyse Doucet.

But I’m avoiding a major dilemma.

I’ve been to-ing and fro-ing about whether to take with me on my hike my much thumbed and much annotated copy of the Divine Comedy.

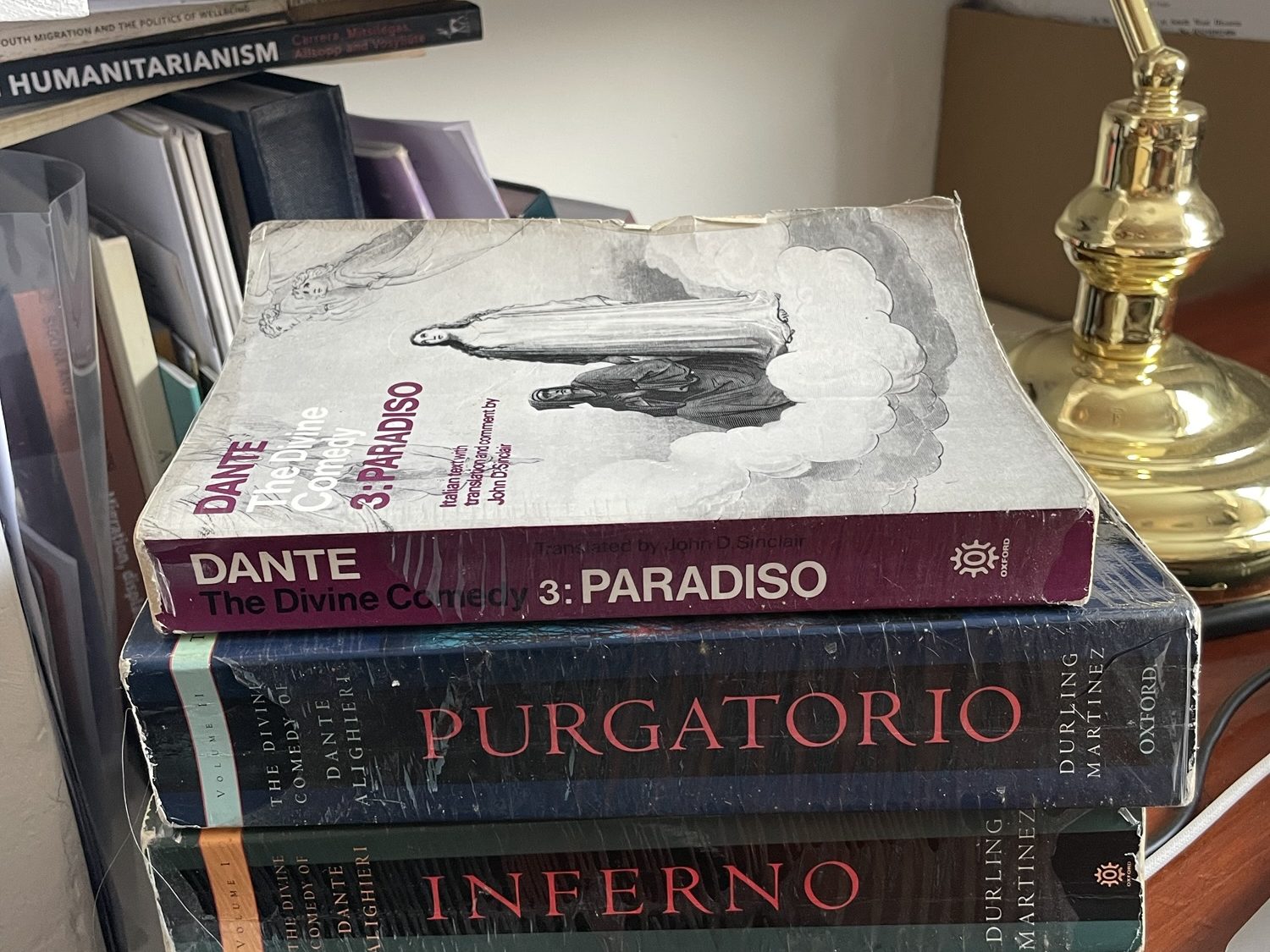

It sits pride of place in my office in three heavy tomes. 2kg of magic. That’s a lot for a pilgrimage of 235 miles through the mountains of Tuscany and Emilia Romagna.

On my travels, I’ve almost always taken these three books with me: Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso. While many people are fixated on Inferno – see the Dante’s Inferno video game which perversely sees Dante rescue Beatrice from Hell – for me, Dante’s journey is definitively a comedy in three parts that traces a journey from darkness and stagnation to light and unfettered mobility.

When the pandemic hit, I got stuck in Guatemala for five months and luckily, I had the books to keep me company. I was living in the US at the time and had gone for a one week writing retreat. When Trump closed the border to foreigners like me, rather than return to England, I was invited to stay with the writer, Joyce Maynard, and pianist, Xiren Wang in a lakeside house.

One evening as the sun set I performed for them the canto of Ulysses with a volcano in the background for added dramatic effect.

‘You were not made to live like beasts, but to follow virtue and knowledge!’ I decried, embodying all of Ulysses’ pride.

One of my annotations reads, ‘Ulysses is Dante’s alter-ego? Am I Ulysses!?’

His tale of defiantly leading his sailors on past the straights of Gibraltar in the face of danger is a warning to all of us who seek to travel to stretch ourselves. I’m sure during my walk I will turn to this passage to push me on but also to ground and console myself when I reach my limits.

Dante writes of Ulysses:

‘neither the sweetness of a son, nor compassion for

my old father, nor the love owed to Penelope, which

should have made her glad,

could conquer within me the ardor that I had

to gain experience of the world and of human vices and virtues’.

(Canto 26, Inferno)

I can relate to this desperate thirst for knowledge, this desire to ‘trapassar del segno’ – to push beyond the boundary. It’s a blessing and a curse.

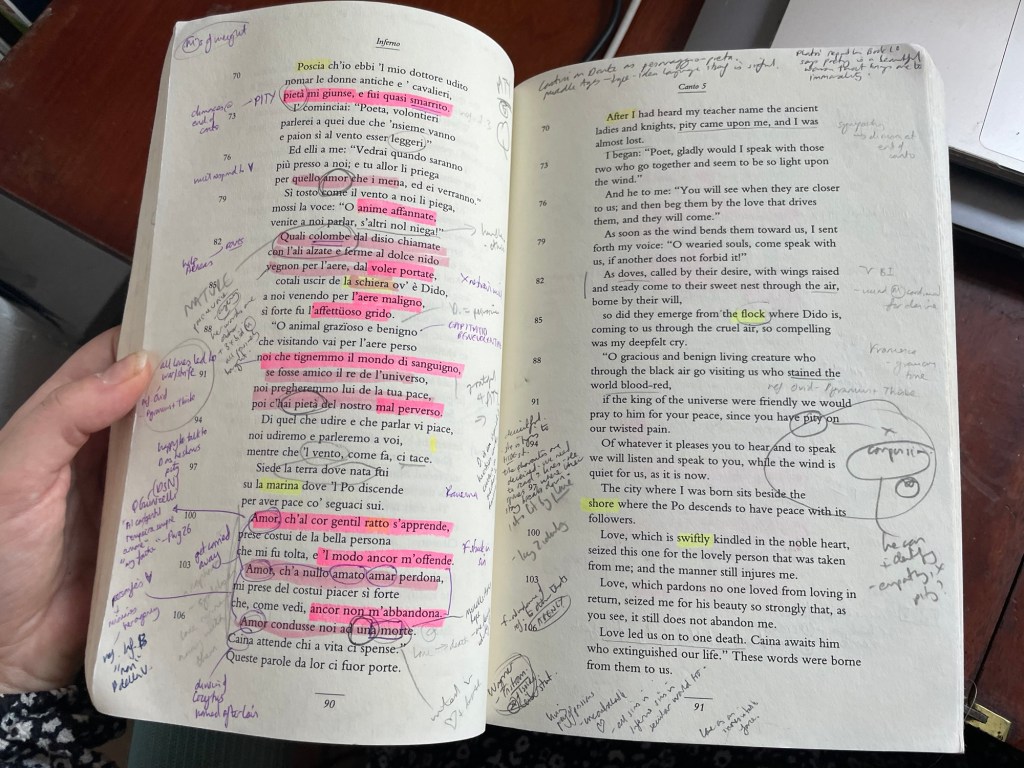

There are at least six different rounds of annotations that I’ve made as I’ve read the Divine Comedy at various stages of my life which are revealed in different fonts and coloured inks.

My first galloping foray through the pages was at the age of 15 when much was inaccessible to me. Still, I swooned at the love story between Paulo and Francesca who were banished to forever spin in a whirlwind of lust in Hell. Their crime: an illicit kiss inspired by their reading of the story of Guinevere and Lancelot. My pencil scrawl reads: ‘love and literature – you lose yourself if you read for pleasure’.

Next are the meticulously crafted notes and highlighted sections from lectures at Oxford where I studied Dante under the expert guidance of Manuele Gragnolati. In a recent article he writes, ‘what does my Europe look like? Like Dante’s: the dream of a more just world’. He speaks about the nomadism that captured him, much like it did me, and inspired an academic career that traversed the world. I had just enough time to lock up my bicycle and dash the steps of the grand Taylorian Library on my first day of lectures to hear him boldly state:

‘Get ready because Dante is a whirlwind!’

He wasn’t wrong.

The next round of annotations, in purple pen, comes from reading Dante in Harvard Yard with Ambrogio Camozzi Pistoja. Autumn leaves swept up in the wind would settle at our feet as we read cantos aloud together as tourists circled the Widener Library. ‘It was founded by a woman who lost her son on the Titanic’, the student guides would repeat as their cotton Harvard scarves flapped in the breeze.

I was based at Harvard to set up a new Immigration Initiative, but on Thursday afternoons I would sneak out of my office to audit seminars on the Divine Comedy. Ambrogio, like me, showed particular sensitivity to the plight of Virgil, Dante’s guide through Hell.

You see, Virgil is swiftly abandoned as Dante moves through Purgatory. Dante is willed to continue his journey to Heaven, but as a non-Christian, Virgil is condemned to return to Limbo.

‘But Virgil had left us deprived of himself –

Virgil, most sweet father, Virgil, to whom I gave

Myself for my salvation’

(Purgatorio, canto 30)

This reading made me sensitive to Dante’s liberal use of guides throughout his journey. The iconic literary figure of Virgil is to Dante as Dante is to me. But ought I not open myself up also to be led by other guides?

In the poem, the pilgrim Dante is accompanied by three guides: Virgil, who represents human reason, and who guides him for all of Inferno and most of Purgatorio; Beatrice, who represents divine revelation in addition to theology, grace, and faith; and guides him from the end of Purgatorio onwards; and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who represents contemplative mysticism and devotion to Mary the Mother, guiding him in the final cantos of Paradiso.

My annotations as Dante abandons his first guide, in no particular order, read,

- ‘WHAT? What about Virgil?’

- ‘Dante cries as Virgil leaves – and he’s not the only one!’

- ‘The paternal authority of Virgil is replaced by the maternal authority of Beatrice. Dante feels intense emotions.’

Dante’s intensity of emotions is just one of the reasons his text so resonates with me.

I felt angry at Dante the author for abandoning his guide. Why could Virgil not have found the same repentance he does?

In Purgatory, Dante works miracles so that Cato can be saved, arguing that the Roman political figure of the first century B.C.E. who committed suicide was a proto-Christian who wasn’t held accountable to Christian beliefs against suicide. While many who committed suicide are condemned to an eternity as gnarled trees in Hell, Cato gets a get out of jail free card. Why? Because Dante could. It was his narrative, just as this blog is mine.

And thus, Virgil is condemned to return to Hell as Dante continues his journey under the tutelage of a new guide.

What can all of this tell me about my own reliance on guides as I walk in Dante’s footsteps? Who will guide me on the Dante trail?

For one, though I am embarking on this journey largely alone, I will be joined at the start by a Ukrainian friend and former student Alina. Halfway through I will be briefly joined by an American marine biologist, Kelsey, who will meet me in Forli. So, I guess, I too, will dabble in the dealings of disposable guides. And who knows who else I will meet on my journey. I penned a list of ‘things I am scared of’ for my therapist Hugh, and among them was ‘I will meet someone annoying who insists on accompanying me’.

‘But that’s great stuff,’ came Hugh’s mirthful reply. ‘well, I mean, it will make for compelling reading…’

But the real guide for my pilgrimage is my text of the Divine Comedy itself. With 20 years of insight into both Dante and my developing mind in the form of annotations it is among my most prized possessions.

Once, in Florence, I had my bag stolen with my copy of Inferno inside. I cried my way through Florence’s multiple police stations until my bag finally emerged with the text still inside. Forget the 200 euros taken with my wallet. I heaved a huge sigh of relief that my copy of Inferno was found. The police were somewhat baffled as I hugged it to my chest.

‘Dante means the world to me,’ I said.

One was amused and gave me a piece of apricot tart.

‘Yes, Dante is pretty special. It’s unusual for a foreigner to realize it.’

The reaction of most Italians to my obsession with Dante is bewildered appreciation and curiosity.

But alas. I have returned with aching shoulders from my hike today – cue Ayurvedic balm – and made the difficult decision that I will not be taking my precious copy of the Divine Comedy with me on Monday when I set off.

The reason? Primarily, it is simply too heavy to carry 235 miles.

And secondly, while I am curious about my annotations over the years, I want to re-discover Dante afresh now, as a 37-year-old woman who is in the ‘middle of the journey’ of her life.

As I set off like Ulysses ‘to gain experience of the world and of human vices and virtues’, may I be open to be guided by something or someone new.

Recommended listening, Lyse Doucet, Desert Island Discs: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0013yzs

Recommended viewing, Lake Atitlan Writing Workshop | 8 Women in Lockdown in Guatemala: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gfnZNnlvdk

Leave a reply to Rowena Allsopp Cancel reply