The unrelenting rain made the path treacherous, and I got lost, only to re-find myself again with new friends eating pecorino.

It wasn’t easy to leave the luxurious round bed this morning, but the weather forecast predicted rain from about midday. The earlier I left, the less chance I’d have of repeating yesterday’s wipe out.

To leave early and avoid the rain or stay in bed and walk for a while beneath the drizzle, that was the question.

I took the middle ground.

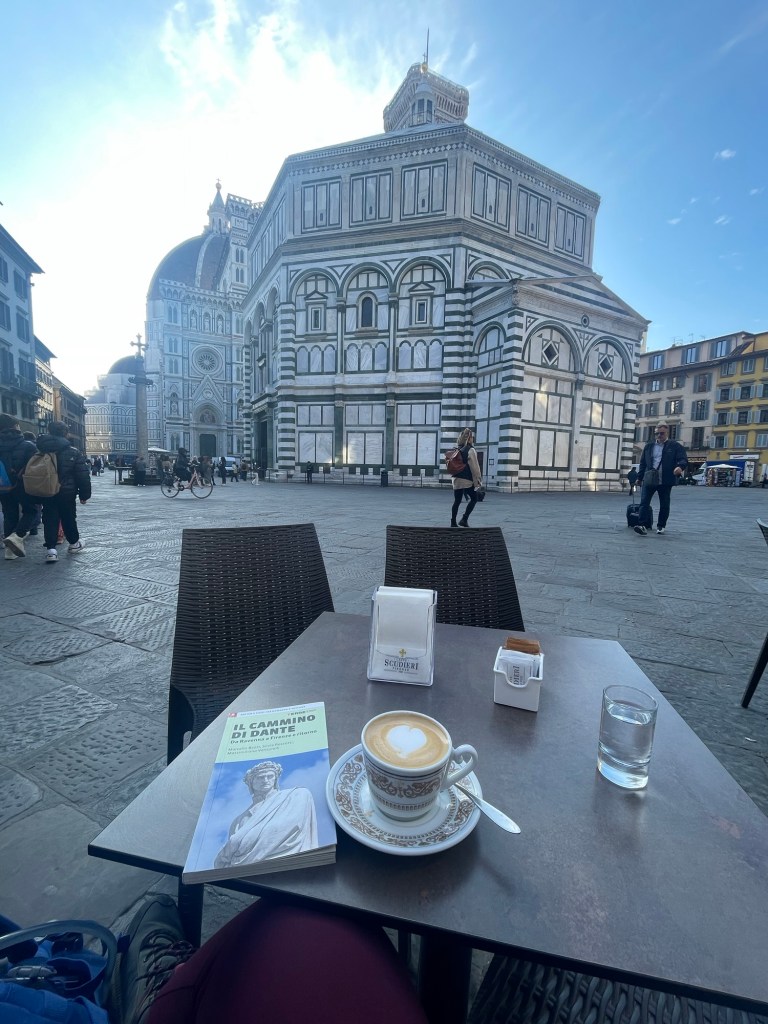

I took my breakfast of a rather disappointing raspberry tart at around 8.30am – my one disillusionment with an otherwise exceptional hotel – and was on the road by 9am.

I’m a savory breakfast kind of girl and one of my only gripes with Italy is the madness of calling a cornetto or croissant a morning meal. Oh no. I’m a vegetarian but I need sustenance – cheese, bread, eggs.

I thought back to the yearly hiking trips I would do in the Lake District with my folks and two other families: the Halsteads and the Milns. Well, the men would go hiking and the women would go to Lakeland Plastics to buy kitchenware. The exception was Barbara. She was, and remains, a badass.

At the Red Lion hotel in the morning before we set off, we’d all have a full English. When I’d ask for the ‘Walker’s Breakfast but without the sausage and black pudding the heavily mustached waiter would respond,

‘But then it’s not a walker’s breakfast, is it?’

Everyone around the table would guffaw. It was an annual joke, and I took pleasure in the familiarity of the routine.

I was dreading the prospect of the 3.5 kilometre hike up the winding road back to the path and had been told the shuttle bus wasn’t running out of season. Still, when I exited the hotel I met Giovanni, the grandfather of six-year-old the Desire with whom I’d exchanged conversation and giggles the evening prior.

‘I don’t suppose if I give you 10 Euros, you’d be willing to give me a lift back up to the trailhead?’ I cheekily proposed.

‘But of course!’ came his reply. ‘And don’t be daft about the money.’

On the way up in his cream leather upholstered 4-by-4, Giovanni pointed out the landslide to one side of the road where men were working to resecure the road. Temporary traffic lights had been installed to aid their toil.

He also remarked on the high number of trees that had been damaged or toppled over.

‘It’s the weight of the snow,’ he explained, ‘the trees have been here for centuries, but they’re not used to these new extreme climate conditions.’

Climate change is an issue that increasingly surfaces in my research with refugees. In my work in Guatemala and Mexico, I found that failing crops are a significant reason alongside poverty and natural disasters why some Indigenous families migrate upwards in search of better opportunities. It’s like the Grapes of Wrath but tipped sidewards on a diagonal axis.

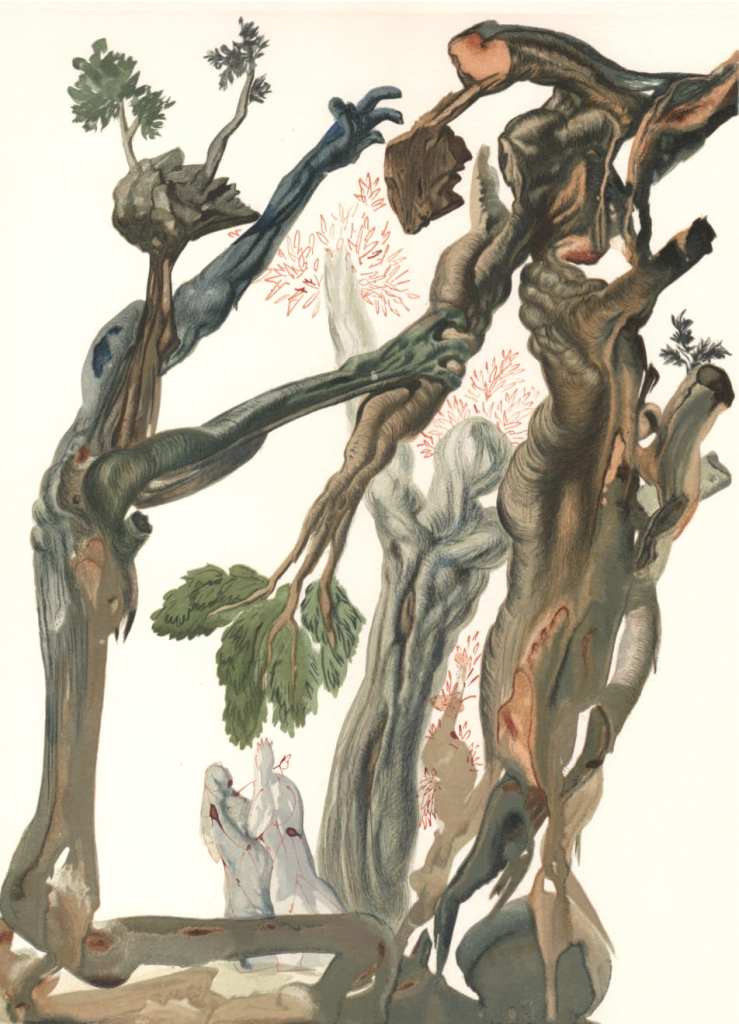

Landslides were nevertheless also a feature of Dante’s time. In fact, he was pretty into Geology. In the Divine Comedy he mentions earthquakes, rivers, the shape of mountains and landslides, a desert of hot sand and some types of rocks (like the marble of Carrara).

The circles that make up Dante’s Hell gradually become smaller with less circumference, as Inferno is depicted like an inverted cone in a sphere, protruding towards Earth’s core. This image is based on calculations of Greek philosophers.

Virgil explains to Dante that the cone in the planet’s surface into which they descend formed when Lucifer, the fallen angel, fell to Earth. Indeed, the impact was so great that it shaped Earth’s surface, with continents formed on the northern hemisphere and the southern hemisphere covered by the sea (Dante didn’t know of the existence of the southern continents of Australia and Antarctica).

In the south, Dante depicted only the mountain of Purgatory. Purgatory, together with the holy city of Jerusalem, forms an axis passing Earth, where Lucifer’s belly sits at the centre. It’s an allegoric image, since Lucifer is damned as far as possible away from the sun and divine light.

In Canto 12 of Inferno, the travelers face a difficult climb down a steep and mountainous rock face. The terrain is passable, albeit tortuous, as if the travelers were making their way in the wake of an alpine landslide. They must climb down a rockslide in order to access the first ring of the seventh circle.

Virgil calls this rocky mass questa ruina (this ruin) and explains to Dante that the ruins of Hell were caused by Christ’s Harrowing of Hell: they are places where the infernal infrastructure was destroyed by the earthquake that preceded Christ’s arrival. Thus, the ruins are a continual witness to Hell’s defeat, its impotence in the face of an all-powerful divinity.

‘The place that we had reached for our descent

along the bank was alpine; what reclined

upon that bank would, too, repel all eyes.Just like the toppled mass of rock that struck—

because of earthquake or eroded props—

the Adige on its flank, this side of Trent,where from the mountain top from which it thrust

down to the plain, the rock is shattered so

that it permits a path for those above:such was the passage down to that ravine.

And at the edge above the cracked abyss,

there lay outstretched the infamy of Crete.’

And with that, Dante and Virgil encounter the minotaur.

It is hypothesized, David Bressan relates, that the landslide is based on the a 3,000 year old landslide near the Italian city of Trento. Dante maybe visited this site, as he lived for a time in the nearby city of Verona.

After thanking Giovanni, I made the steep climb upwards to Mount Falco, passing a Madonna of the Forest.

Angel fibre was draped over the distant trees that peeked out between trunks. And higher still were more rounded clouds like those in Renaissance paintings. For a moment I imagined that I was in the world of Sonic the Hedgehog, like you could just jump and land on one of them to reach a new level.

The path expanded into a big field strewn with tiny blue wild flowers and animal droppings the size of olives. An army base sat to my left. I nearly took wrong path but I double checked after yesterday’s 3-kilometre detour.

The moss, like socks, covered the trees’ stems in a vibrant green.

And then I suddenly found myself in a snowy landscape.

Using the compass on my phone I decided to head back down to where I’d come from and just walk off piste in the direct of Fiumicello. I would give it 30 minutes and if I hadn’t re-found the path, I would have to give up and face the unappealing four hour hike back up the path I’d made back to Passo della Callo and call today a write off. Tears pricked at my eyes. I hated the thought of defeat.

With a foot of snow beneath me, I dug my heels in to keep my balance as I descended. Crocuses pushed up through snow, determined to mark the Spring.

The snow made it hard to make out the path, obscuring the tracks of pilgrims prior. Moreover, the rain in the night had formed a thin skin of ice over the terrain. Now I really was skiing – reliant on my sticks not to fall forward.

I followed the signs that looked like the polish flag, red and white, and proceeded tentatively to the sound of birdsong.

The snow soon soaked through my boots and there began seven hours of squelching forward with saturated socks and shoes. The water in my boots bubbled through the top of the canvas, reminding me of the jacuzzi I’d luxuriated in last night which now felt a world away.

In these treacherous conditions, it took me nearly 2 hours to descend 5 kilometers.

I wasn’t cold until the rain came at around 10.30am. My hood up, I reflected on the epicentre of Dante’s Hell where we meet Satan writhing in a lake of ice. Unlike many popular depictions of the time, Dante’s Hell was not all fire and brimstone. Rather, while we encounter fire in the higher spheres, the more serious crimes are punished by a frozen sense of total immobility.

In the belly of Hell are Judas, Brutus and Cassius who each writhe in one of Satan’s three mouths.

For Dante, the very worst sin was to betray one’s hosts like they did – perhaps something informed by his refugee experience.

I’m sorry to be the one to tell you, but the commonly cited proverb attributed to Dante that ‘the deepest parts of Hell are reserved for those who stay neutral in times of conflict’ is simply not true.

I stuck to the side of the path where the snow was thinner and, without phone signal, I blindly carried on. The fog was now so thick that anything more than five metres away was obscured.

I eyed a footprint which appeared to be fox, or a wolf perhaps, and another that looked like a deer.

When I came to a steel barrier in the path with barbed wire either side, I shimmied my body around the side of it, clinging to the metal frame. I was back in a videogame.

Without peering down at the precipitous drop, I carried on. There is no public right of way in Italy as in England, but I’d learnt in my six days of the cammino that to make progress, ‘no entry’ signs on this trail are largly to be ignored.

I soon came to doubt this fact and felt foolish as I followed signs into a huge prairie where the straight path was well and truly lost.

Still with no phone signal and with my hard copy map of little use for its sparse detail, I spent about an hour circumventing the huge stretch of grass looking out for a red and white sign. There was nothing to be found. I heaved my body and rucksack up to the top of the hill to see if the advantage point would reveal the path but alas, there was nothing. I was well and truly fucked.

The anti-anxiety drugs I am currently taking helped me resist the temptation to panic, though my heartbeat was still racing at twice its normal speed. I could see tracks running here and there, but the mud and pools of water made the animal and human tracks indistinguishable.

Worried about water getting into my phone again, I used my chest as a ledge to protect it, walking forwards like a hunchback one step at a time. I found myself crossing my fingers and suddenly, out of the mist, there is appeared! A red and white lick of paint on a tree.

Hallelujah!

A few metres after that I saw a Cammino di Dante sign and, by God, I have never been more relieved to see a little block of wood – thank you Oliviero for your toils!

I took a deep breath but couldn’t stop to process recent events since the rain was now pouring and there was absolutely nothing in the way of shelter at any point today on the route. I had told my therapist Hugh that one of my fears for the walk was that an annoying fellow hiker might attach themselves to me, but in that moment, I would have given anything for a companion. I felt utterly and completely alone to face my fears. I had a first aid kit and a tinfoil blanket, but I hadn’t even thought to bring emergency flares with me. What was I thinking?

The path for the next three hours was literally just like sliding down a waterfall. I slipped about five times and banged by arm on a rock but the damage was superficial. The bank was so steep that with one proper fall you would go hurtling down the mountain side.

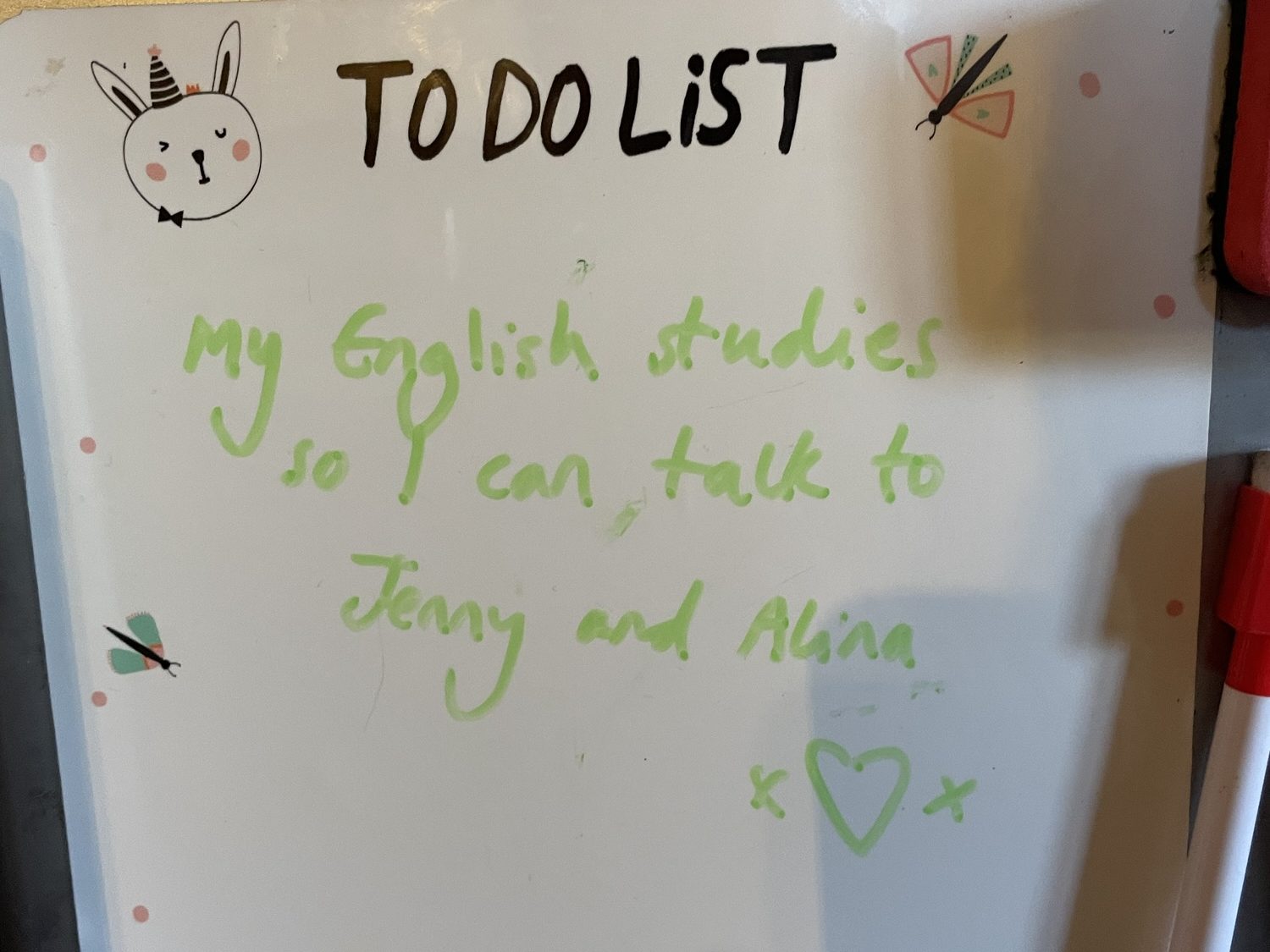

I had to balance pulling out my iPhone from my bra for directions with the risk of water damage and, since the charge had run out, I also had to plug it into my power bank which I tucked into my pocket. The cable caught up in the necklace Alina had gifted me and now I thought of her words of encouragement as I navigated the puddles and the precipitous edge. Forza, Jenny, forza! ‘You are destined to complete this trail.’

I’d gone from digging my heels into the snow this morning to walking sideways in a snowplow to try and defeat the soggy leaves which collected at the bottom of my poles like I was a garbage collector. My fingers had become like prunes and my boots thudded on the rocks for the extra weight of the water they had accumulated.

As I descended into Fiumicello – literally meaning little river – the muddy banks of the stream on my right side had given in so that to walk through the path was to walk through water.

I finally found some shelter under the porch of a house in the tiny hamlet of Fiumicello and untangled my iPhone cable which had stopped charging from the power pack. I had noted that the plastic was coming loose yesterday and now, though I’d applied an ample amount of the cellotape Alina had left me from her Mary Poppins style bag this morning, it was doggedly refusing to function.

Hopefully I’d have enough battery to make it the further 5 kilometers to Premilcuore, then I didn’t know what I’d do about the charger. Perhaps tomorrow would be a write off. I’d have to spend it getting a bus to the nearest supermarket in a larger town? I felt defeated.

As I walked along the road from Fiumicello to Premilcuore I passed the stations of the cross and towering cliffs in which the rocks had been confined to cages to avoid damage to the path.

Finally, I descended into the charming little town of Primilcuore – meaning squeeze heart – and was somewhat surprised that the first person I’d seen all day was wearing a hijab.

I easily found my B&B, la Rosa della Rabbia, where my hostess Nadia could not have been more welcoming. When I asked about the iPhone charger she calmy replied,

‘No worries! You can use mine or else they sell hem in that tiny Tobacco shop just down the street.’

I could not believe my luck. I headed straight there and purchased a golden thread of cable that was labelled as ‘extra resilient.’ I breathed a huge sigh of relief. An older lady in the shop was playing lotto.

‘Long day?’ she asked me.

‘Just a bit,’ came my reply.

Back in my room I peeled off my shoes and socks to reveal heels turned white from eight hours of soggy walking. They were cratered with little marks like the surface of the moon.

Eyeing up the bin I was disappointed that it looked more akin to the size of a mug so there would be no foot bath for me today. Instead, I bundled myself into the shower and held the nozzle up close against my toes, spraying them, one-by-one, back to life. Then, at my mum’s advice I wrapped my feet in a warm towel with Nardo oil.

Emptying the contents of my rucksack, the coffee I had packed had exploded and the dried spaghetti was now moist in the bottom of my bag. I threw on my spare pair of clothes that had only got partially wet and went next-door for an onion and cheese Piadina, an Italian sandwich made with soft flat bread.

As I ate, I got talking to a friendly local man, Alim, of Moroccan origin, who was sipping on a white Russian – ‘like coffee, but a cocktail’ – he informed me. He was wearing a fashionable adidas tracksuit and fixed eye contact as he spoke to me.

I told him I had been surprised to see the lady with the hijab on my entrance into the village.

‘Oh yes, we’re quite a few here,’ he replied. ‘The first Arabs came in 1989.’

We exchanged some conversation in Arabic, at which he seemed at once delighted and surprised. Alim had five kids and was a social worker who supported the elderly and people suffering from poor mental health.

‘You have to speak to old people and poor people if you want to understand life,’ he said.

On his neck were three tattoos of stars which increased in size as they reached his earlobe.

I told him I had visited Morocco and had good friend, Fatima-Zohra, in Fez, where there exists one of the oldest universities in the world.

There followed a heated discussion between myself, Alim and Nadia about whether social sciences were worth studying at all – Nadia had an undergraduate and masters in Sociology and Criminology, the specialism of the department where I teach at the University of Birmingham. Alim also sought to convert me to religion.

‘You cannot read Dante or any philosophy for that matter and not be religious,’ he insisted, ‘we never have an original thought, we just receive it.’

His speech was strewn with adages and beautiful words,

‘Poetry,’ he remarked, ‘is the skin of a language that you cannot graft or translate…sorry, when I drink, I become a philosopher.’

We discussed all things abolishing the police – or not, and Nadia told me about her thesis on the mafia in the region we were now in, Emilia Romana, and dreams of pursuing further studies in psychology. Her boyfriend listened in but did not engage in the conversation.

As I munched on rosemary flavoured crisps, Alim chastised me and bought me a plate of local pecorino – ‘much healthier,’ he said. ‘Do you like tequila?’

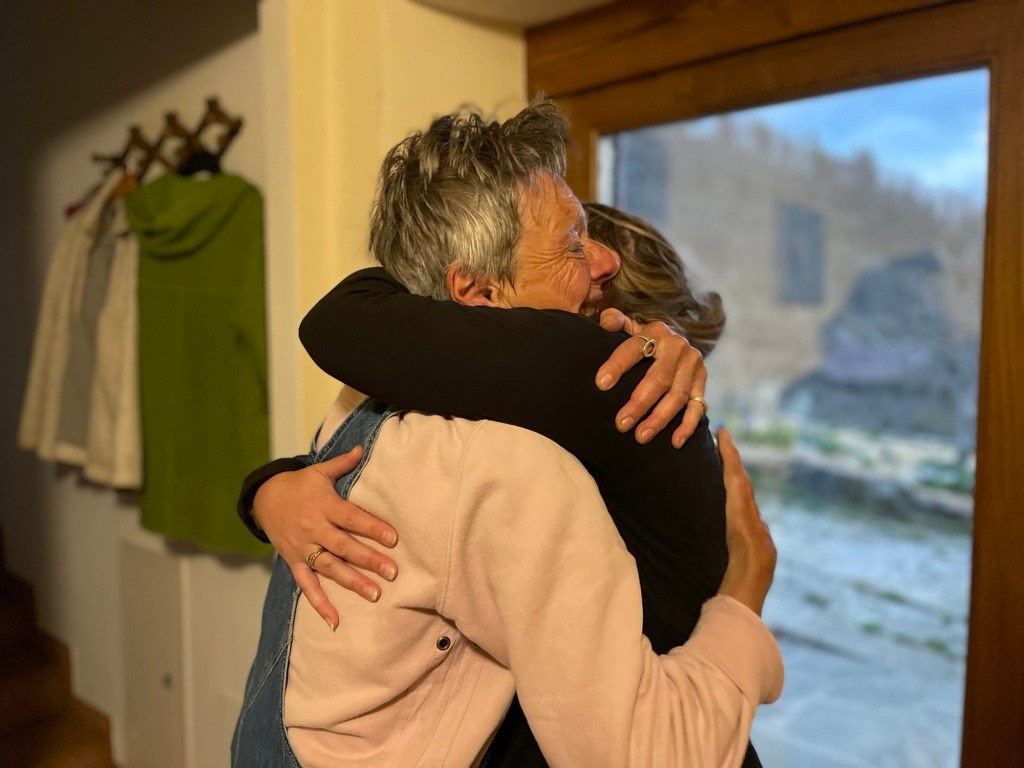

It was 10pm when I left the restaurant. I’m not sure I managed to convert Alim to the delights of social sciences, just as he made little headway in converting to me religion, but the next day I received a text from Nadia,

‘Thanks for everything, and especially for giving me hope in pursuing my passion,’ it read.

Recommended reading: KNOW Your Rights: A Critical Rights Literacy Framework Based on Indigenous Migrant Practices across Guatemala, Mexico, and the United States (available in English and Spanish): http://collections.unu.edu/view/UNU:9673#viewAttachments

Recommended reading: The Grapes of Wrath: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Grapes_of_Wrath