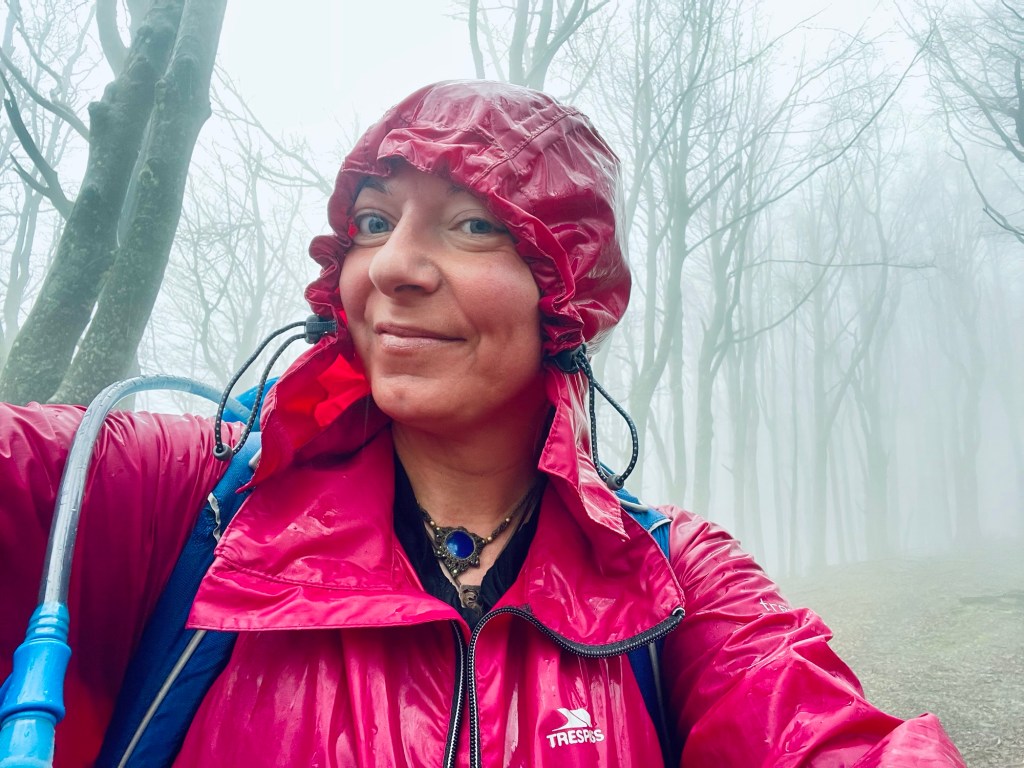

I got lost four times and made the stupid decision to scale a towering fence.

Marcella, the owner of the Agriturismo Tenuta Mazzini where I had spent the night, came to greet me in the morning. She was on her way to work as a primary school teacher. I didn’t hesitate in exuding my passion for her place.

‘It’s a marvel,’ I said.

I always felt a slight anxiety when I had not walked for a day, but I had slept amazingly in the comfy bed, and I felt well rested as I heaved on my backpack and set off down the road to Dicomano.

It was 10.20am and the sun was shining brightly. The air was fresh. Two cows greeted me from an ample field.

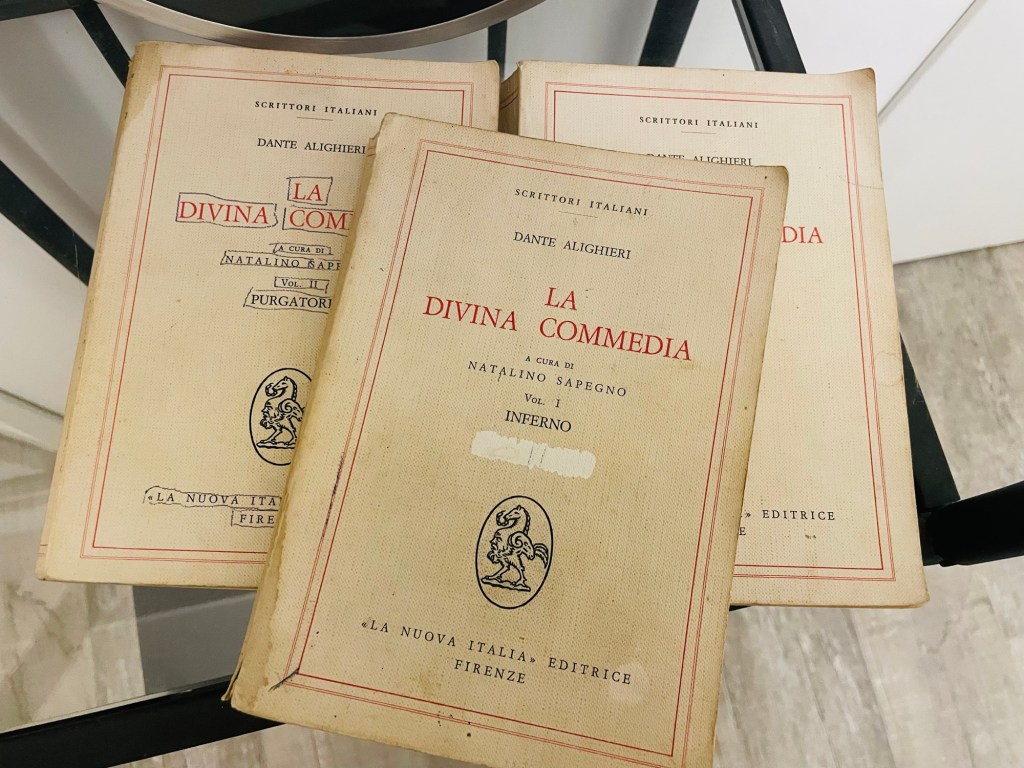

The day’s walk began with the descent back to Dicomano where Dante was summoned for a political meeting during his exile from Florence. I’d been spending a lot of time with Dante the poet and so it was interesting to spend time with Dante the politician. It was here that he had sought to forge alliances between the Ghibellines and the White Guelfs of whom he was a member. Like many refugees, Dante had been multiply displaced. His brief stay in Bologna had been interrupted when the White Guelfs were barred from the city.

I passed an excavator that was digging up the Earth as I wound down the road and stopped momentarily to pet a ginger tom cat.

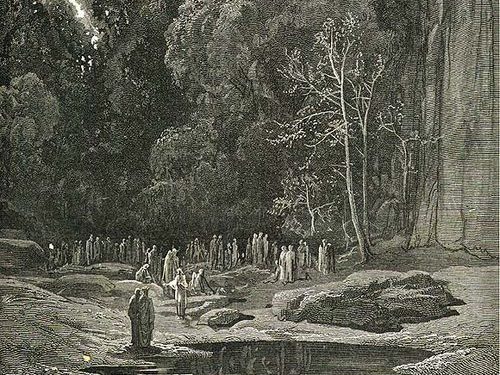

I followed a Dante trail sign off down a small, steep woodland path to the right and was soon kicking up the leaves again. I crossed a small, gurgling waterfall where the path split in two.

I went left, which would transpire to be the wrong choice.

Conscious of not walking with my phone attached to my hand, I had tucked it into my sports bra so that it was fifteen minutes before I realized that I was very much off the beaten path. I was glad I was wearing trousers and not shorts as the brambles and trees assaulted me, leaving bloody snags on my arms and hands. I held onto the tree branches to heave myself up the bank towards the road. I’d thought about going back to where I’d lost the straight path but decided to carry on. The map suggested that in a few metres I would re-reach the road from which I could proceed my descent into the medieval town.

Climbing up on my hands and knees, the mud collected beneath my fingernails. Nettles attacked my ankles and, as I passed a network of two waterfalls, my weight dislodged a huge chunk of earth from the ground.

I assumed I had made the usual mistake of following an animal track. I passed through two olive fields and there was the road ahead of me, just a short way down from where I’d strayed.

I had basically done a 45-minute loop of the forest for absolutely no reason. If I had stuck to the path, I’d be eating pizza for breakfast by now but instead I was weary, thirsty and had no idea from whence I’d come. I paused for some water and let the blood dry in a thick smear on my hand. My knees were filthy from the climb.

I passed through an open gate and exited onto a hill from where I could see the town before me. I had no idea what to do. The end was in sight and so I just kept climbing, trying to reach the road, my knees and knuckles deep in the foliage as if I were massaging the Earth. I wished I could just jump or fly over to the car park.

Now all that stood before me and an espresso macchiato and pizza slice was a massive metal fence which was decorated, at the top, with a thick mesh of vertical barbed wire.

The road was right there, but as I stumbled around the fence’s parameter, I couldn’t find a way to cross. Two metal gates were tightly fastened with thick wire which I tried in vain to unpick, clumsily sliding my fingers between the holes in the gate. There was nothing for it, I couldn’t go through or under it: I would have to go over it.

As I climbed up onto a wooden ballast, my bag pulled me back and so I threw my weight forwards, held tight to the fence and swung my leg over. The second one followed and I jumped down, only to land on the roadside with a thud, the full force of which shot up into my left foot.

The familiar pain immediately hit me and I knew I’d broken something. Luckily, from the quick survey of the discomfort, I deduced I had just damaged a toe or two. This was nothing like the agony of when I’d broken my metatarsal in Guatemala when headed out on a hike to locate the national bird, the resplendent quetzal. I took some Ibroprofen for the pain and carried on into the town centre where I’d spent some time yesterday in Dante’s footsteps. My hands were covered in a cocktail of mud and blood.

It was 12 o’clock which meant I had spent almost an hour and a half scrambling around in the woods including 15 minutes trying to unpick the lock and 15 minutes working out how to get over the fence. I’d bruised my knee and cut my trousers on the barbed wire but I had made it back onto the road. A smartly dressed lady was walking past with her dog.

‘Are you OK?’ She said.

‘Yes,’ I replied, though I wasn’t. ‘I just got a little lost.’

I sat on the verge and ate an apple. Next time, I’ll take the road. I could have been well on my way to Dicomano by now, but as it was, I hadn’t even reached the starting point and the steep climb meant I’d exhausted at least half of my supply of water.

And that was how in the middle of the journey of my life, I found myself in a caged olive grove for the straight path was lost.

I hobbled to a bar and ordered the much craved for coffee and pizza. I removed my shoe and tried to wiggle my left middle toe. No, it wasn’t moving. The sellotape Alina had left me finally came in use. I used it to attach my broken toe to the ones beside it. We had evolved from three toes creatures after all: the three middle toes already moved as one.

I noted a urinal built into the cliff face next to a busy garage which had a wolf mural painted on the wall.

Five men were drinking beer in the café.

‘Ok, let’s start again,’ I thought. It was 12.30pm.

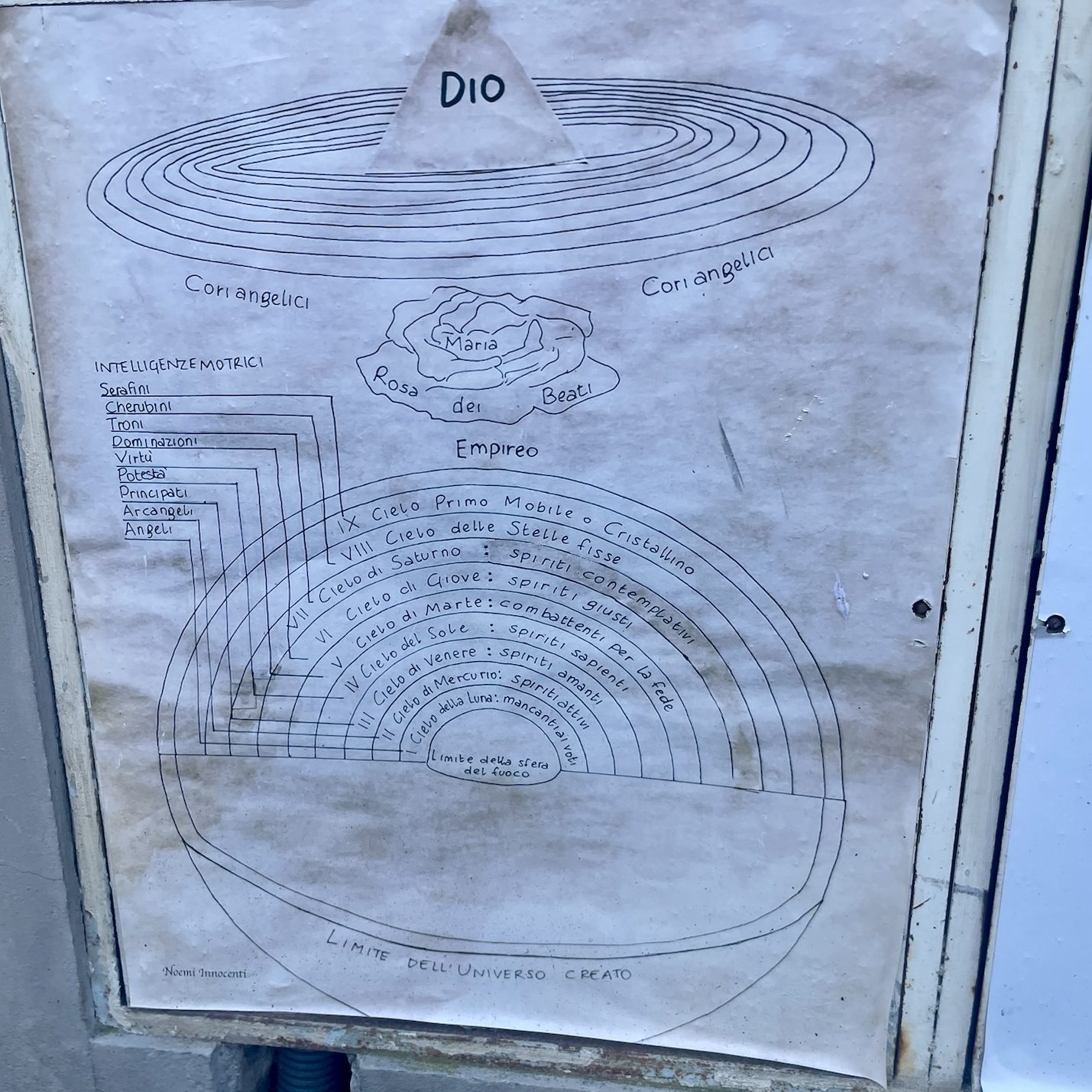

On the surrounding streets were quotes from Dante’s Paradiso that had been plastered to the wall and here was a map of the heavenly realms as he had understood them. One quote read:

‘The handsome image those united souls,

happy within their blessedness, were shaping,

appeared before me now with open wings.Each soul seemed like a ruby—one in which

a ray of sun burned so, that in my eyes,

it was the total sun that seemed reflected.’

In the Divine Comedy, Paradise is depicted as a series of concentric spheres surrounding the Earth, consisting of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Fixed Stars, the Primum Mobile and finally, the Empyrean.

Back on the path, I passed a balcony on which stood a lady watering Calla lilies beside a hyper vigilant black cat. She smiled and wished me a ‘buon viaggio.’

As I left the town, there was a cemetery on the left, sweeping trees to the right and, of course, the village football field.

I followed the signage, making sure to check directions on my phone every five minutes now, and made my way up a steep concrete road. From a garage there emerged some antique porcelain sinks and toilets.

I moved in and out of shadows, enjoying the litter of red leaves on the pavement that were the colour of Alina’s hair. Tom had told me yesterday that you could eat dandelion flowers and so I folded one into my hungry mouth. The entire plant is edible, from the flowers to the roots. It tasted bitter.

I proceeded past a field of goats that came with a ‘beware of the goats’ sign and an agriturismo which was decorated at the front by a beacon of lemon trees.

The path had expanded out into a beautiful hobbit like landscape. I sat on a rock and drank some more water beside a prairie and a tinkling stream. A white butterfly with orange tips fluttered past, then a yellow one. Two black beetles were mating on my backpack. They were covered in red spots like inverse ladybirds. I noted that I was developing callouses on my hand from the rub of my hiking poles.

I could see back down to the town in all its majesty. There was a house built into a tree which was surrounded by a cluster of bracken. The simple way to tell bracken apart from ferns is that bracken has a stem, and will come up singly. Ferns, on the other hand, generally don’t have a stem but rather always have multiple fronds coming up from one central point.

I realized I was lost again and there followed an agonizing half hour hike up a steep bank that was littered with spiky horse chestnut seeds. I had somehow managed to drink all of my water and kept stopping to catch my breath. At one point, my cap was disturbed by an overhanging branch and I had to retrace my steps downwards some ten metres to retrieve it. It was a chalky blue and read, ‘Stay wild and free, protect our sea.’ I had purchased it from a Royal National Lifeboat Institute giftshop in Wales the previous summer.

I thought of Will and Jo’s non-wedding wedding that I would be attending that weekend back in London. Their party theme was ‘under the sea’ and my friends at home had been feverishly making costumes, including one for me.

I stopped to pull out some horse chestnut spikes from my hands and finally re-found the path. It was 3pm and I’d only hiked some 12 kilometres and climbed nearly 120 floors but I was only about 6 kilometres along today’s 17 kilometre stretch of the cammino. My arms looked like I’d had a fight with the cat. I flicked an ant off my leg.

The path followed an ancient Etruscan way which was dotted with sign posts with orange cones on the top which resembled Asian hats. I trotted downhill now, my bag chafing under my armpits, enjoying the spectacular view to the right of the mountains in the sun. They were striped in shadow and light.

Two lizards were wrestling beside the bushes and the trees were squeaking in the light breath of the breeze. I really wanted some water.

Then I realized that in my stupor I had gone wrong yet again. It was a fifteen minute hike back uphill. Today was not my day.

It was tough on my knees and broken toes hiking downhill, but I was thankful to have finished the climb and grateful once more to Franco in Marradi for fixing my right hiking pole. A farm appeared to my left with goats and a horse.

I got lost for the fourth and final time, climbing nearly all the way up a really steep hill covered in scree only to backtrack. A cock crowed somewhere in the distance. It was 5pm.

An aloe vera plant emerged from someone’s garden and I was so thirsty I contemplated ripping off a leaf, opening it out and licking the sweet sap. The irises that decorated this lawn were purple and pink in hue.

I ate some berries from my trail mix thinking they might have some moisture inside. The sun was beating down and I had my eyes peeled for an outdoor tap.

Then, just as quickly as the thought arrived, such a tap appeared. It was accompanied by the outline of a dog and dog bowl but, water was water. I guzzled from the font and refilled my pouch. I held the water in a precious sphere in my mouth before I swallowed it.

I could feel that I was back in Tuscany because of the rolling hills, the soft golden light and the way the olive leaves seemed to glitter in the evening sun. The approaching dusk made the hills look matt and hazy.

A bird sounded out like a car alarm. It was suddenly so tranquil. I recalled the words of William Blake from his poem Auguries of Innocence

‘To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.’

I watched a plane soar through the sky and was once again reminded that, this time next week, I’d be finished with walking and back to normal life. I wondered how normal my life could ever be after this adventure.

I watched a plane soar through the sky and was once again reminded that, this time next week, I’d be finished with walking and back to normal life. I wondered how normal my life could ever be after this adventure.

A tractor drove past, and I collapsed in the grass awhile. I was 20 minutes from my destination but my toes ached and I was exhausted from all the extra energy I had expended on getting lost today. I had been told by my French host Beatrice that there would be pesto pasta for dinner and I was sure that it would be delicious.

The final descent into Dicomano was stunning. Poppies once again lined the hedgerows coupled with thick clumps of thistles. A chorus of sheep bleated out in unison.

There was a horse medallion on someone’s house and statues of little angels and a chicken rendered in bronze. There was plenty of space for both me and the cars on the road. A chain of colourful beehives lined the hill like a Lego brick house under construction.

Three men who were tending to a cement mixer said hello as I passed them and, embarrassed, I realized I’d been singing to myself the nursery rhyme The Grand Old Duke of York. Today had certainly seen me march to the top of the hill and march back down again.

Then came the familiar sweet waft of black locust or white robinia. A plough was stationed in the middle of a field, retired from the toils of the day. An elderly voice was shouting to a young child something about a horse and dirty trousers.

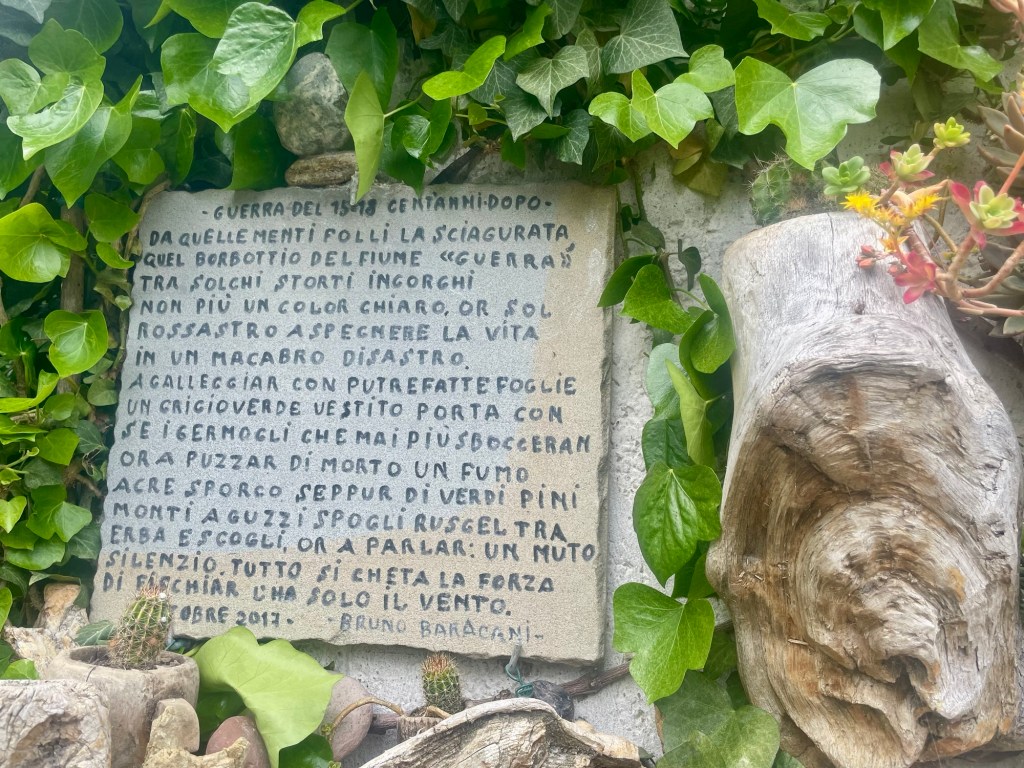

I was greeted by my host, Ivan, who called me ‘bambina’ and complemented me on my pigtails – they were cute but also practical hiking wear. Their bed and breakfast, Pino del Capitano sat in a beautiful Mediterranean garden that was decorated with colourful Portuguese tiles and sinuous sculptures.

That night, I dined on a delicious fare with a man working in construction from Udine who was also staying with Ivan and Beatrice. Unlike me, he was here for business, not pleasure.

Ivan brought me some plasters and I lanced my toes together more forcefully. He was sympathetic since his own daughter was a hiker who had recently completed 45 days of the Camino de Santiago. He was 74 but seemed much younger for his friendly and exuberant demeanor.

‘Every stone you see, every flower, that’s the work of my hands in the garden,’ he proudly explained.

It had taken him 25 years to get it just right.

We must ‘cultivate our garden’ counsels the French writer Voltaire at the end of his satirical quest, Candide. After the day I’d had I enjoyed the peace. Too true, I thought, too true.