Today’s hike zigzags the Tuscany and Emilia-Romaña borders across the Apennine ridge where ghosts from historic battles give it a spooky air.

I woke up at 6am to see Alina off. Massino Kyo had kindly offered to take her down to Prato Vecchio to catch the bus back to Florence from where she’d take the train. Refugees in Italy are obliged to not leave their accommodation for a certain amount of time or they lose it. So, despite her newfound love for hiking, the prospect of Alina continuing with me wasn’t possible.

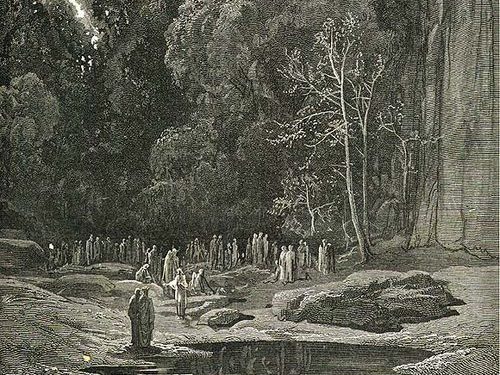

Unlike when Virgil leaves Dante in Purgatory, suddenly and without warning, Alina and I shared a meaningful hug goodbye. Also in contrast to Dante, I was now completely alone, without a fellow traveller or guide.

Alina had left me a little glass vial of Chinese ointment for my aching limbs. She also accidentally left her impractical mismatching socks which were glittery: a sea blue and an emerald green. Though every ounce counts in long distance walking, I carried them with me. I was too sentimental to throw them away.

At 7am I was cooking ravioli to take with me for lunch. The weather forecast predicted rain and I had ahead of me a steep climb of 23 kilometres and 255 floors up.

I was on the road by 9am as I had to wait to go over the calculations of the heating costs in extensive detail with our host. This is something I’ve only ever encountered in Italy – that in B&B’s you pay only for what you use in electricity.

It was a steep climb up out of the village and the rocky terrain reminded me of the White Mountains where I’d hiked in New Hampshire during the year and a half I lived in Massachusetts. I’d joined a meet-up group called Ridjit where we carpooled to go on walks most weekends. I joined the Appalachian Mountain Club and by the end of my time there, I’d succeeded in climbing 14 of the 48 4,000-footers. I’m determined to go back and cross off them all.

The path was uneven and steep and composed of grit and stones. This stood in contrast to some of the other paths I’ve trodden on the cammino which are scattered with shards of terracotta and old tiles in shades of pink, white and blue. As a mosaicist, it has been difficult not to succumb to the temptation to pick up little pieces, but I know the extra weight is not worth it.

Mushrooms jutted out from tree trunks like fairy ledges making me think of the Enid Blyton book, The Magic Faraway Tree which my Granny would read to me in bed. We used to call her Granny Daisy though I’m not sure why. Perhaps because of her beautiful little garden and for the fact she once worked as a florist. It’s from her that I get my love of flowers.

At 11am the rain was immanent so I stopped by the bridge of Prato Al Fiume to eat some of my pasta which was still warm. I sat on a plastic bin liner which I’d unfolded to make an improvised tarpaulin. I’d brought with me Tupperware and a travel set of cutlery and now I stuffed rocket into my mouth with spinach and ricotta and bit, apple-like, directly into a chunk of pecorino cheese.

The Via dei Legni, or ‘way of the woods’ has long been a place of cross-border encounter and trade but also of fighting. The North Apennine mountains ridge weaves across the border of three regions of Italy: Liguria, and also Tuscany and Emilia Romagna. I crossed between the latter two, straddling the nature reserves of Sasso Fratino and Pietra.

Casentino, the Tuscan land between Arezzo and Florence, is the first valley of the river Arno – the same river that flows through Dante’s hometown of Florence. I could imagine that the enduring presence of this river was a great comfort to him, hence the ubiquity of rivers in the Divine Comedy.

The abundant waterfalls and streams, which also feature in the Comedy, are a legacy of the glacial age.

If the water is one of the great riches of the high Emilian Apennine, we mustn’t forget that this is also due to the unusual microclimate. The area has record rainfall, exceeding, on occasions, 2000 mm of rain per year. The region is also known for its cumulonimbus, or thunderclouds, the only cloud type that can produce hail, thunder and lightning. The base of the cloud is often flat, with a very dark wall-like feature hanging underneath and it sometimes lies just a few hundred feet above the Earth’s surface.

Today the clouds started as white slivers but, as I ascended the Faggiolo mountain, they soon became a panorama of white which engulfed the sky like curtains at an opera.

The gray-blue clouds, laden with water from the Tyrrhenian Sea which is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy, rise up with the thermal winds and clash against the Apennines. They are an integral part of the landscape of the ridge, and one I was to come to know all too well.

While yesterday we had contemplated the rolling green hills, now the crown of surrounding mountains was obscured from view by the mist which served as an uneasy companion to the Spring blossom.

Shortly after eating, I arrived at the Monastery in Camaldoli, a monastic complex located within the municipality of Poppi, in the heart of the Park of the Casentinesi Forest. The place used to be known by the name Fontebuona – literally, ‘good fountain’ – because of the high quality of its waters.

And with that the rain began to fall.

I had planned to visit the nearby castle of Poppi yesterday. Here Dante had been hosted for one year by the Guidi Counts in 1310 and here he likely wrote parts of Inferno.

But my visit to Poppi on this occasion was not to be. Instead, today I contemplated Dante’s time in exile as I listened back to audio recordings of my Reading Dante with Refugees project and made voice notes into my iPhone.

As the panorama became spookier, with clouds hanging in the trees like gigantic cobwebs, I also contemplated Dante’s time in the military.

Between the castles of Poppi and Romena, on the plains of Campaldino on June 11, 1289, a 24-year-old Dante took part in the Battle of Campaldino between the pro-imperial Ghibelline troops from Arezzo and the pro-papal Guelph troops from Florence. It was likely he was on horseback.

It was a fierce clash in which Dante’s side, the Florentines, won but there were many fallen soldiers on either side. It is estimated that some 1,700 Ghibellines died and around 2000 were taken prisoner. The battle marked the beginning of the hegemony of the Florentine Guelfs over Tuscany which subsequently split into two factions – the black Guelfs and the White Guelfs of which Dante was a part.

Indeed, Dante was exiled for being a White Guelf in 1302 when the Black Guelphs took control of Florence. The Blacks continued to support the Papacy, while the Whites were opposed to Papal influence, specifically the influence of Pope Boniface VIII who Dante prophesizes as being condemned to the eighth circle of Hell, that of the simoniacs.

Simony is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things.

Dante directly references the Battle of Campaldino in canto 5 of Purgatory where the reader might be surprised to find a slain Ghibelline soldier granted redemption. From the terrace of those who have repented last minute and died in situations of violence, Bonconte da Montefeltro, interrupts his singing of the Miserere to speak. In the canto, three souls tell of their violent deaths: two in battle, and one at the hands of her husband. Bonconte da Montefeltro is the second soul who speaks to Dante.

After he led the Ghibelline cavalry at Campaldino, Bonconte’s body was never found on the battlefield. Instead, he explains to Virgil and Dante, it was carried by the elements into the river Arno:

‘…across the Casentino

there runs a stream called Archiano—born

in the Apennines above the Hermitage.There, at the place where that stream’s name is lost,

I came—my throat was pierced—fleeing on foot

and bloodying the plain; and there it wasthat I lost sight and speech; and there, as I

had finished uttering the name of Mary,

I fell; and there my flesh alone remained.His evil will, which only seeks out evil,

conjoined with intellect; and with the power

his nature grants, he stirred up wind and vapor.And then, when day was done, he filled the valley

from Pratomagno far as the great ridge

with mist; the sky above was saturated.The dense air was converted into water;

rain fell, and then the gullies had to carry

whatever water earth could not receive;and when that rain was gathered into torrents,

it rushed so swiftly toward the royal river

that nothing could contain its turbulence.The angry Archiano—at its mouth—

had found my frozen body; and it thrust

it in the Arno and set loose the crossthat, on my chest, my arms, in pain, had formed.

It rolled me on the banks and river bed,

then covered, girded me with its debris.’

Through describing the fate of Bonconte’s body, Dante gives us a stark description of the weather conditions in the region.

Dante does not glorify violence. Quite the contrary. Teodolinda Barolini, Editor-in-Chief of Digital Dante writes that ‘when I read the Commedia, I am always struck by how forcefully Dante communicates historical pain.’

In Inferno 12, the violent are immersed in a river of boiling blood, the Phlegethon. Meanwhile, in canto 21 of Inferno, Dante demonstrates empathy for the opposing soldiers who were defeated in the siege on the Caprona Castle in August of 1289. It is possible Dante may have also fought in this battle. He recalls the fear of the opposing side as they walked among their enemies following surrender:

“so I saw the troops fearful as they left Caprona under treaty,

finding themselves in the midst of their many enemies”.

I was grateful for my hiking poles which I have not used until now as I made my way across the hostile terrain of the thick woodland.

After hours of climbing uphill, I was so relieved at the prospect of going down that I missed my turning and took a 3 kilometre detour, having to climb back up the path from which I’d come. The view was completely obscured by the clouds.

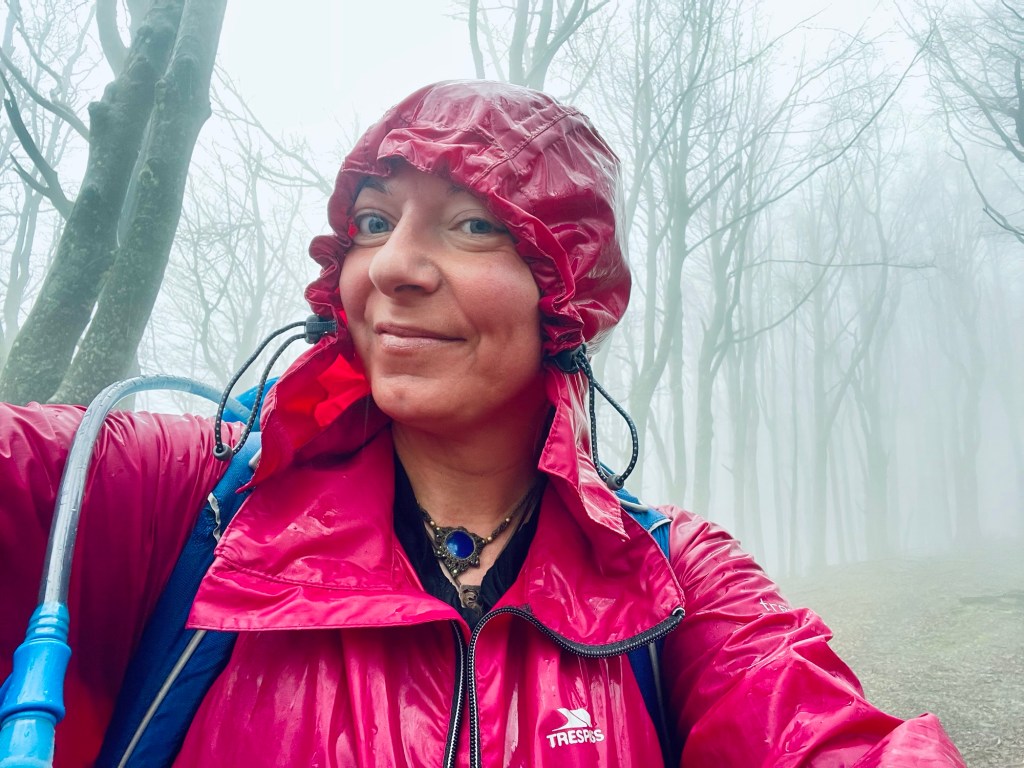

As the rain metamorphosed from mist to drizzle, I covered my backpack with its light waterproof cover, sending contact lenses spilling across the mud as I removed it from a pocket at the front of the bag. I tucked my phone into my sports bra so that I could continue listening back to my Dante class recordings. I had bought earbuds, but hiking alone I felt vulnerable and wanted to preserve my senses.

The combination of sweat and rain pooled in my eyes which stung from the sun cream I had pointlessly applied that morning. As I got my phone out to check directions – the amazing team at Cammino di Dante have made a GPS of the walk – the water also saturated my power bank, causing my phone to alert me that water had been detected in the charging cable.

My biodegradable phone case eroded from the rub of my breasts.

I jogged some of the downhill in the afternoon to make up lost time, using my sticks like a four-legged animal. The path was well trodden but abandoned. My heavy backpack thudded against my spine with every step.

I took a selfie and reflected how the flaps of my pink cagoule hung at my ears like Dante’s wimple. I felt like I was skiing as I rushed down the path, trees surrendering to my sight on either side.

Just after the Monastery in Camaldoli, I met the first fellow hiker of the day who was coming in the opposite direction, an Austrian woman who had a bad knee. She informed me that she had stayed at the same hotel to which I was headed and that it was luxurious. This motivated me to plough on with the steep climb back up.

At one point, to my left there appeared a mound of snow. I thought back to yesterday when I was dressed in old shorts and a t-shirt – an 80’s set up of leopard bottoms and a neon top that I could dump if needed. I had packed clothes for warm and cold weather but the contrast between the two days could not be starker.

I took a short break at 2.30pm, huddling under a protruding rock that served as a grotto for shelter – the first cover I had encountered all day. I couldn’t get my layers right – I was sweating but my hands were also starting to go numb. I truly felt like I was climbing Mount Purgatory as I weaved my path, staggering up and across the two regions.

I arrived at Passo della Calla at around 3pm then made the 40-minute descent down a steep, zig-zagging road to the Hotel Granduca in Campigna. The sky was white, not grey like when it rains in England.

Phalanxes of pine trees lined the road, some of which had been damaged by the winter snowfall. Here and there, waterfalls cascaded down from where they had been diverted by man to preserve the road. I tried not to think about the climb back up that awaited me tomorrow.

I arrived at the hotel reception soaking wet. My purple leggings, in their sodden state, had turned a darker plum hue.

Booking the Hotel Granduca was a treat for me at 100 Euros a night – much more expensive than most of my accommodation. But by God was it worth it.

I made use of the spa, contorting my body in the water to project the jets onto the aching arches of my feet. And the bed in my room, which had its own personal sauna, was round! What novelty.

I had my first meal out of the trip: a sweet onion soup on which I burnt my tongue I was so eager to devour it, and a plate of tagliatelle marinated with local mushrooms.

A little girl sat playing games on an iPhone behind the bar. It turned out she was the daughter of one of the owners.

‘What’s your boyfriend’s name?’ she asked me, handing me a little note with her name on it, like a business card.

‘I don’t have one.’ I said.

‘Come no!’ she exclaimed. She then proceeded to inform me that her own boyfriend Salvatore, was also 6 years old.

Finally, after a day walking in isolation, I’d made a friend.

Recommended reading: The Magic Faraway Tree by Enid Blyton: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Faraway_Tree