The last stretch to Ravenna boasts two magical gardens where I would meet a friend and a soul mate who showed me that Dante’s divine love is at once self-reflective, shared and in harmony with the natural world.

Kelsey and I had a leisurely breakfast at our lodging, Fattoria Chiocce Romagnole, with the two fellow male Italian pilgrims and our host, Rossella. She explained a bit more about the flooding that had occurred in the region on the 17th of May, 2023, a date that she had tattooed on the inside of her left arm. The water had come in through the windows where we were now eating fresh apple cake made by her mother.

‘The most disturbing thing was the screams of the animals in the night,’ she said.

She had lost one goat and saved another by giving it mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. A lot of the birds perished. In the morning, the fire service had come in a dinghy to rescue her dogs.

‘At least here the water was clean,’ explained Rossella, ‘further down it became muddy and even more treacherous.’

A green and yellow parrot called Raul clung to her chest as she spoke, dipping its beak occasionally into some milk.

Rossella recounts her love for her animals in episode 3 of the podcast, Respirano ancora (‘Still they breathe’) which is called The End of Eden.

There is much of Eden in Rossella’s farm, a place that Dante visits in the last three canti of Purgatorio.

Here, atop Mount Purgatory, Dante returns to the prelapsarian perfection of the place from which Adam and Eve were expelled after eating the forbidden fruit.

In canto 28 he tells us it is the ‘place chosen as the nest for human nature,’ the place given by God to Adam and Eve as a ‘mortgage on their eternal home, until they defaulted on the loan.’

In canto 29, he continues,

‘While I moved on, completely rapt, among

so many first fruits of eternal pleasure,

and longing for still greater joys, the airbefore us altered underneath the green

branches, becoming like an ardent fire,

and now the sweet sound was distinctly song.Full of astonishment, I turned to my

good Virgil; but he only answered me

with eyes that were no less amazed than mine.I halted, and I set my eyes upon

the farther bank, to look at the abundant

variety of newly—flowered boughs;Here, mankind’s root was innocent; and here

were every fruit and never—ending spring;

these streams—the nectar of which poets sing.’

Rossella’s farm is certainly a place for poets to sing about. The scent of organic lemon trees mingles with jasmine and turkeys and hens roam free across the perfectly mowed lawn. Dogs and cats co-habit with affection and swallows circle out of the barn which they have come to call home.

Though she is humble, Rossella is clearly also aware of the magic she has created here, something that is perhaps all the more special because it was almost lost.

Two peacocks called Dante and Beatrice flirt beside olive trees. This is poignant for it is in the Earthly Paradise in canto 30 at the end of Purgatorio that Dante finally meets his beloved Beatrice. He realizes she has arrived when he ‘recognizes the signs of the ancient flame’.

‘a woman showed herself to me; above

a white veil, she was crowned with olive boughs;

her cape was green; her dress beneath, flame-red.Within her presence, I had once been used

to feeling—trembling—wonder, dissolution;

but that was long ago. Still, though my soul,now she was veiled, could not see her directly,

by way of hidden force that she could move,

I felt the mighty power of old love.’

The parrot flew over the Kelsey and began nibbling on her long brown hair.

We spent the morning catching up with work in the garden surrounded by the four donkeys, Mais, Judith, Quedo and Nerina. They would come over and give us a friendly nudge or nibble here and there. Two rams circled us without menace and there descended a real sense of peace.

A man called to check whether the five hives of bees had succeeded yet in producing honey.

After lunch we set off for the 19 kilmetre walk to Ravenna where we would meet the great man himself, Dante Alighieri. We stopped for a coffee at the restaurant Trattoria da Luciano where some of his cantos were hung up on the wall.

The path followed the river Montone and the scenery was much like yesterday: agricultural and strikingly flat.

A road sign warned of crossing children and Kelsey commented that it reminded her of signs back home in San Diego that warn of immigrants crossing the road from across the border. As two bikes came thundering past, she bent down to rescue a ladybird that had an iridescent beak. A poppy hesitantly rose its head.

We were in the middle of discussing what the ‘social’ means in social policy research when a fit man with walking poles called Walter passed in the opposite direction and wished us a good day.

‘Are you pilgrims?’ he asked.

It turned out that Walter was a seasoned walker who had done the cammino di Dante some years before when he’d had to take several long diversions because of landslides. Now he was training for his next adventure. I tried to convince him to head to England to tackle the Pennine Way, while Kelsey advocated for the Pacific Crest and John Muir Trails.

Quite to our surprise, right there and then, he whipped out a weighing scale with a hook on the end and insisted on weighing my bag.

‘15 kilos!’ he cried out. ‘What on earth are you thinking, you should have a maximum of 10, how have you made it all the way from Florence?’

Suddenly the blisters made sense.

He advised us to stop at the house of Giordano Bezzi, the founder of the cammino which we would pass in about 5 kilometres on our way into Ravenna. He was certain that we could just show up unattended, even though it was Easter weekend. Perhaps we would.

‘You’ll recognize the house from the huge Dante sculpture outside,’ he advised.

We passed some road works and three places where the path had been cordoned off by metal fences and barbed wire. Now seasoned to the trials of Italian walking, I knew to head under, round or over them. I tossed my bag over first, careful not to damage my laptop, and then threaded my body around the wire. Kelsey dexterously followed.

We passed a man in a green shirt who was tending to his vegetable garden with a hoe and took a break to eat slices of apples with peanut butter. A random plastic chair that was covered in graffiti was situated in the verge beside the river.

Kelsey and I discussed Tuvalu’s climate refugees and the efforts the people are taking to preserve their culture. Our next topic of conversation was where in the afterlife we would locate certain politicians.

As the path became more substantial, we navigated a traffic jam caused by a tractor which suggested that we were nearing the city.

Then, there it was, the face of Dante rendered in metal with one eye looking in and another looking out.

As we descended the path to the yellow house, a cockerel skitted past a yellow camper van. Would he be in, this Giordano Bezzi, of whom we’d heard such elevated praise?

It turned out that he was.

The next six hours flew by. In one of those encounters that happen rarely in one’s lifetime, time stood still.

Giordano was everything I could ever have imagined of the founder of the Dante trail: an effervescent, extraordinary man who I can only describe as a creative genius.

In the time we spent together, he showed us around his spectacular garden and told us something of the origin of the trail. Though he’d worked as a pharmacist, now, in retirement, he was a musician and an installation artist. Much of his work is inspired by Dante’s invitation to look inside ourselves as well as out.

‘Life is all about reflections and uncertainties,’ he counselled.

As I followed him through his sprawling garden which was on the cusp of bloom, I thought of Purgatorio, canto 28 once more’\|| ,

‘Now keen to search within, to search around

that forest—dense, alive with green, divine—

which tempered the new day before my eyes,without delay, I left behind the rise

and took the plain, advancing slowly, slowly

across the ground where every part was fragrant.’

The peonies had flowered early. They were struggling to keep their heavy heads up on delicate stems. They were verdant, vibrant, huge.

Some fruit trees had exploded in a blossom of pink and white. Irises lined the path here, and there we entered into a surfeit of melancholy willows before which sat another piece of art.

‘Come back in two weeks and it will be a riot of colour,’ he insisted.

Every tree, every flower he had planned and planted with his own hands. I felt like Dante being shown by Mathilda the Earthly Paradise in canto 29 of Purgatorio.

‘following her short

footsteps with my own steps,I matched her pace.’

And then there was the art.

Here was a sculpture of Don Quixote’s horse made out of tin cans, forks and kettles. When he had presented it, he had ridden it forwards towards a fan that sprayed out pieces of newspaper. This was the windmill, the ‘fake news’, he explained.

And there, a rendering of Monet’s Giverny emerged from the grass complete with the bridge.

He had previously installed mirrors to reflect the water.

The sunset lit up the sky and, as Dante puts it, ‘little birds upon the branches were in the practice of their arts’.

I felt like I was witness to the spectacular procession Dante observes in the Earthly Paradise, a forest full of life. Introduced by heavenly songs and blazing lights, Dante sees a burning seven-armed candelabra approaching. Each of the seven candles gives the sky one of the colors of the rainbow. Then a procession follows: 24 elders, four beasts with each six wings covered with eyes, one of them a griffon drawing a two-wheeled chariot, at its left wheel there are three ladies, at its right four, then there follow two men, four humble men and finally an old sleeping man.

But Giordano, at seventy one, was full of life.

As Dante describes Eden,

‘a sudden radiance swept across

the mighty forest on all sides—and I

was wondering if lightning had not struck.But since, when lightning strikes, it stops at once,

while that light, lingering, increased its force,

within my mind I asked: “What thing is this?”And through the incandescent air there ran

sweet melody.’

Suddenly, it was 9pm and we hadn’t thought to eat.

‘Fear not,’ said Giordano, I have peas. ‘And let’s put in some laurel to give it the taste of Dante.’

Thus, we ate a delicious supper together of peas marinated in freshly harvested onions, stock and laurel leaves. Kelsey and I contributed a spinach and cheese crescione and a great deal of gratitude. Her and Giordano also ate some rabbit that was reheated from the night before.

The conversation flowed like water.

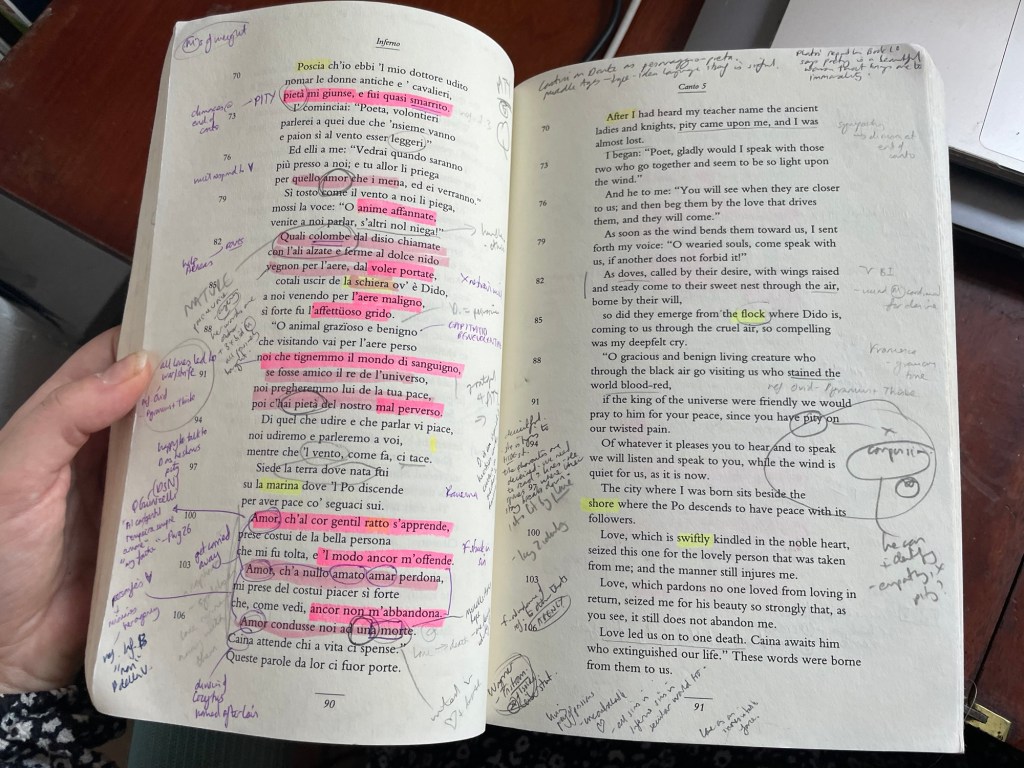

Giordano was as enthusiastic to share his own passions, which comprised jazz – including Kelsey’s favourite, Charlie Parker’s album, Bird –, Pirandello and women’s liberation, as he was to hear about mine. I gifted him a copy of our Dante on the Move anthology and a T-shirt with the front page logo that had been designed by Alina. He was thrilled.

At 10.30pm we called the hotel in Ravenna to say that we were running late and, after a few more episodes of precious conversation, Giordano gave us a lift into the city in his van.

In the van, we still couldn’t stop talking. In a frenzy of new friendship, we were finishing one another’s sentences. This was unreal.

He was intense but so was I. And, for once, that was ok! In fact, it was more than ok, it was appreciated, cherished even.

When was the last time I had felt so seen?

Giordano dropped us by our lodging, Hotel Centrale Byron, and we dumped our bags before making the short walk around the corner to Dante’s grave. It was nearly midnight, and we had the whole place to ourselves. We sat before the great poet on the cold cobbled floor.

I read Kelsey the blog I had written ready to publish in the morning and, as I did so, tears filled my eyes. It felt so special to be reading my work out loud here to her, before the bones of Dante. I had made it to him and now all that was left was to return to Florence in his honour.

We purchased some red roses from a Bangladeshi street seller called Mashalim which means ‘to be safe, secure, at peace.’

Two of them we threaded through the bronze gates of his mausoleum; the other one I gifted Kelsey and the fourth I would carry with me to Florence to place outside his cherished San Giovanni where Dante had so desired to return to be ‘crowned a poet’.

We returned to the hotel, slightly disappointed with the filthy carpet and 80’s bathroom décor after what had been such a jubilant day.

I was contemplating how on earth I could show my appreciation for Giordano when there appeared a message on my phone.

It read:

‘Flowers are not only in gardens,

but they also walk with a backpack,

the scent of intelligence that you leave

is inebriating and indelible.

Your garden is the work with those

young refugees, you manage to sow

flowerbeds with smiles, you work like

a bee, you build bridges of

looks, you gamble with

invisible things.

Your pen becomes the sting

for stupidities and blindness,

I will certainly eat your honey.’

‘I fiori non sono solo nei giardini ,

ma camminano anche con lo zaino,

il profumo di intelligenza che lasci

è inebriante e indelebile.

Il tuo giardino è il lavoro con queiragazzi, tu riesci a seminare delle

aiuole con i sorrisi, lavori come

un’ape, costruisci ponti degli

sguardi, giochi d’azzardo con le

cose invisibili.

La tua penna diventa il pungiglioneper le stupidità e le cecità,

Certamente mangerò il tuo miele.’

I stroked the necklace Alina had gifted me of the almond plant which flowers before it bears fruit.

Perhaps my honey was also in the process of production on this cammino.