Florence feels like my home, though the city I grew up in couldn’t be more different.

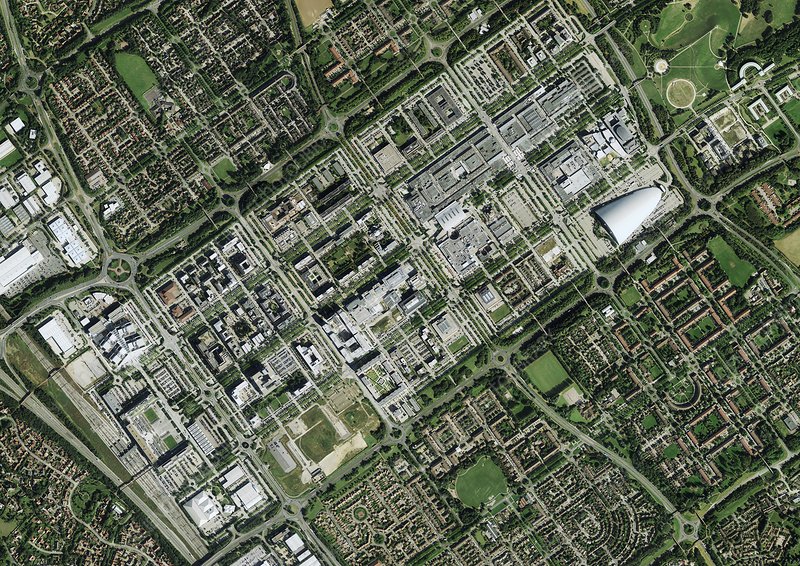

Coming to Florence has always felt like coming home to me. It’s peculiar since I grew up in Milton Keynes which is known as England’s ‘best new city’. It’s a capitalist paradise with grid roads based on San Francisco and dozens of roundabouts. It has a city centre founded on a shopping centre and an indoor ski slope that looks like a slug.

It’s quite the contrast to Brunelleschi’s famous Duomo, but then I suppose Florence was also built on the accumulation of new capital. Somehow I find the aesthetic of the latter more appealing.

I cried as I spent a Christmas mass there overwhelmed by how at home I felt. Duomo does not mean dome as many might suppose. Rather it stems from the Latin Domus, for home. In one of my favourite Italian books, La luna e I falò (The Moon and the Bonfires) Pavese writes, ‘we all need a home town, if not only for the chance to leave it’ (Un paese ci vuole, non fosse che per il gusto di andarsene via.)

I got the tram into the city centre from the airport as I have so many times before, living in Florence as a Visiting Professor at the University and returning a number of times to give talks about my work reading Dante with refugees in the last two years.

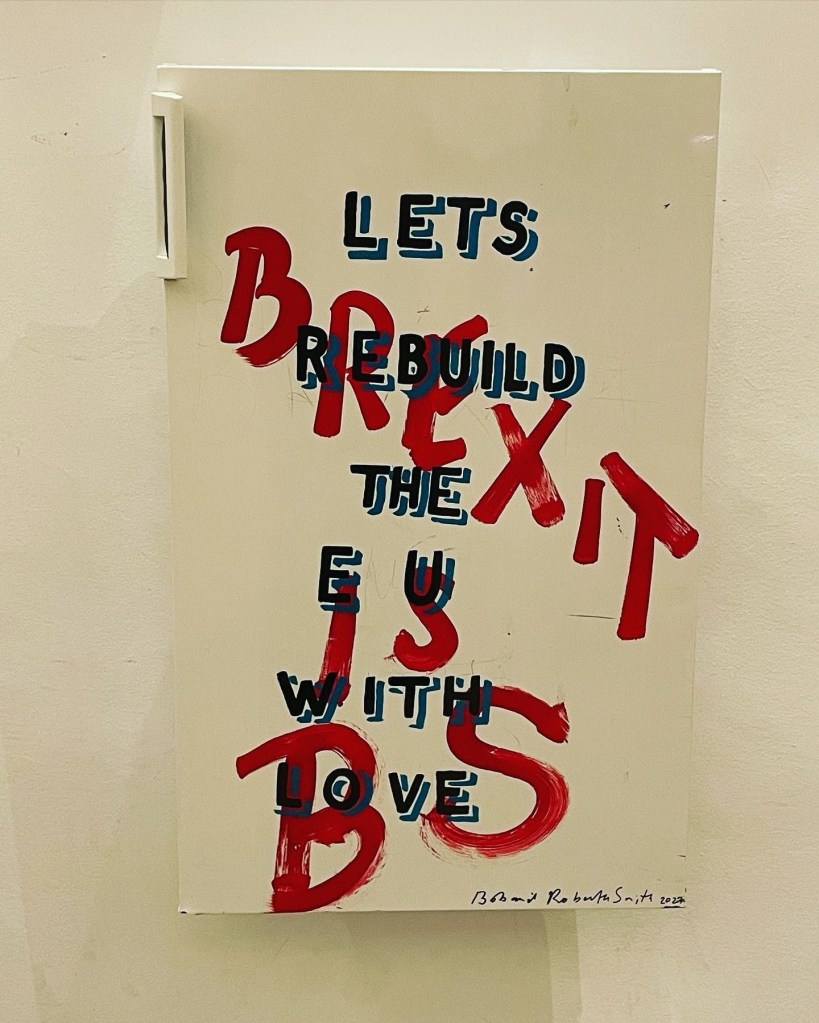

I smiled at the little ‘tss tss’ of my ticket at it registered in the little yellow machine. I’d had to wait about an hour at arrivals listening to banal conversation in the non-EU passport queue – thanks Brexit! I got chatting to one family visiting Florence for the first time.

‘You’re going to be blown away,’ I assured them.

When they asked me what I did I told them, and as usual I was greeted with an opinionated diatribe about what the UK needs to do to solve it’s ‘refugee problem’ and stop the scourge of ‘boat people’.

‘If we are a country that had a navy that could colonize the world we have the capacity to save refugees from drowning in a stretch of water the size of Scotland,’ came my reply. ‘It’s a question of political will’.

Sometimes I lie and say that I’m a hairdresser, but I felt like the fight.

By the time we had passed the 20 minutes to Santa Maria Novella I’d made some headway in talking them down from a Reform stance, but in my experience it takes about 45 minutes or a long taxi ride to genuinely ‘change hearts and minds’. I felt a little less guilty about taking this time as work leave – as academics who care about the subject of our endeavors we are in some ways always working.

On arrival in the centre, I was greeted with the familiar sites of the Yamamay lingerie shop where I’ve spent way too much money in recent years and groups of black faces sitting on the steps outside the train station.

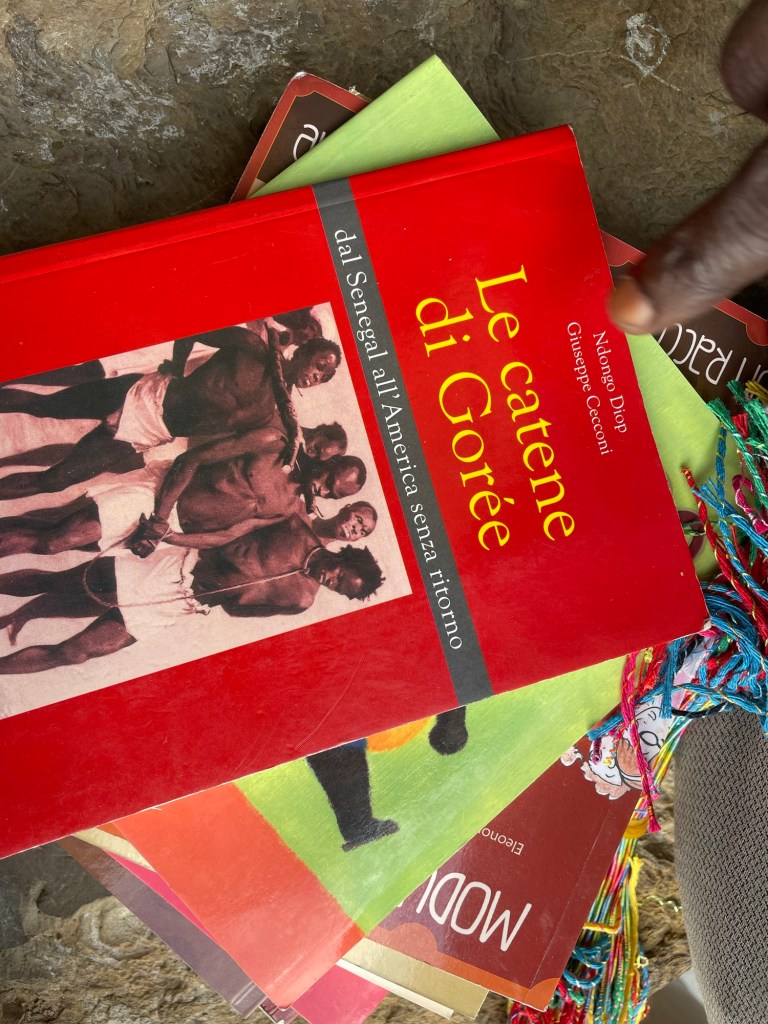

‘Kenya, Senegal?’ I asked one friendly face. He carried over his arm a brocade of African bracelets and under his other arm some books in Italian and English about slavery. It’s a smart business I’ve observed across Italy. When I was living in Rome it was rare to leave a bookshop without encountering an African face who sought to sell you something of their violent history.

‘Senegal!’ Came the reply. And we continued to discuss in French how his life was progressing in Florence; how business had been that day.

I asked him about the war in Casamance providence, the longest running conflict in Africa, where I’d worked with women peace activists as a journalist at openDemocracy 50.50.

‘It’s hard,’ he said, ‘but in Italy life is a little easier’.

We parted ways after our brief chat – I didn’t want to distract him from his business – and he gave me one of dozens of friendship bracelets I’ve accumulated in my discussions with the African street sellers.

I knew from experience to take it and that, unlike in many situations with migrant sellers, my receipt of the gift wouldn’t be followed by a request for money. A relationship – however fleeting – not a transaction had been established.

‘Au revoir, Madi, bonne chance!’ I offered as I heaved my backpack back onto my shoulders and made my way to the Santa Maria Novella Square. Maybe I should put in a funding application to do an ethnography of African street sellers, I mused.

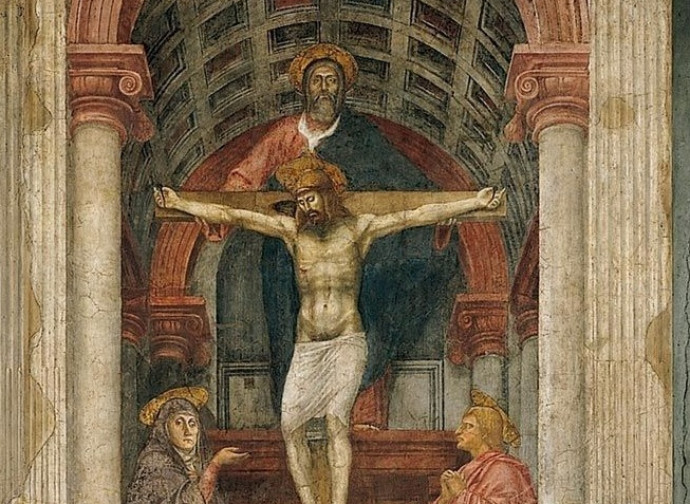

In Santa Maria Novella I headed straight to the church where I wanted to pay my respects to one of my favourite paintings in the city, the Trinità by Masaccio. It’s known as the first painting in Western art that uses the principles of perspective. I’d need that if I was to spend 20 days hiking the 235 miles of the Cammino di Dante through central Italy.

I remember first seeing it when I came to Florence as an eager 15-year-old art lover. I’d studied it in school and even done some sketches from a post on Wikipedia before Google was a font of unlimited images. I think back then I’d asked Yahoo or Jeeves.

‘Can you see mum, all the lines point backwards into an invisible vanishing point. This is no ordinary depiction of Christ’.

She was suitably impressed and then, as now, a chance to process the monument of Masaccio’s revolution in European painting was proceeded in the form of a strong coffee in one of the colourful cafes that line the square like lace.

I knew that even though I had hardly slept that at 2pm, I would be chastised for ordering a cappuccino – this is a breakfast drink in Italy not to be taken after midday. I took a double espresso macchiato and turned my face into the Spring sun awhile.

The term cappuccino comes from the capuchin monks who resemble in their brown habits and shaved heads the caramel colouring of the cup’s rim and the dollop of foamed milk in the middle. You don’t get a sprinkle of chocolate or nutmeg here in Italy unless you ask for it, this is a foreign invention.

From Santa Maria Novella I spent the afternoon trotting happily through the narrow streets, observing the signs detailing which famous figures had occupied said building. Galileo. Leonardo da Vinci. There were all the greats, it was enough to look up. And on the street corners, known as cantos, like the sections that make up Dante’s Divine Comedy, there appeared the all too familiar Medici crest.

The six balls that make up the shield are disputed as to their origin. Some say they represent medical compresses – pills were yet to be discovered in the Renaissance – harking back to the Medici name which means doctors in Italian. Still others claim they depict oranges – also good for your health and a frequent feature in frescos depicting the family.

From Santa Croce the colossal statue of Dante constructed by Enrico Pazzi to mark the 600th anniversary of Dante’s birth glared down at me. Though I knew better than to seek to procure a ticket last minute in tourist season, I knew that inside the walls of the church sat the tomb of Dante erected by Stefano Ricci in 1830.

In it, he appears topless and macho, symbolic of the newly unified Italy and all things nationalism. Though he dreamed of and wrote at length about a unified Italy and glorified the Holy Roman Empire, Dante’s own stance on nationalism was more nuanced and I felt he’d be somewhat miffed to see himself depicted in that rather uncouth way, tits out, topless without his classic red cape, hood and white ear flaps.

More to the point, unlike the tombs of Galileo and Machiavelli, his was empty.

And here comes the whole point of my pilgrimage, his bones lie in Ravenna, my destination, where he died in exile.

His grave in Florence is a reminder of the vicious battle that still continues between the two cities about where Dante’s remains and his legacy should reside.

On a fieldtrip with a group of refugee students back in Spring 2023 responses were mixed. Some felt it was desperately sad that Dante hadn’t been able to return to Florence but that as the place that has hosted him, Ravenna was entitled and duty bound to be the custodian of his remains. Others felt that Dante would have wanted his bones to be returned to his beloved home town in recognition of the fact that he had, as he had prophesied in the Divine Comedy, ‘returned as a poet’.

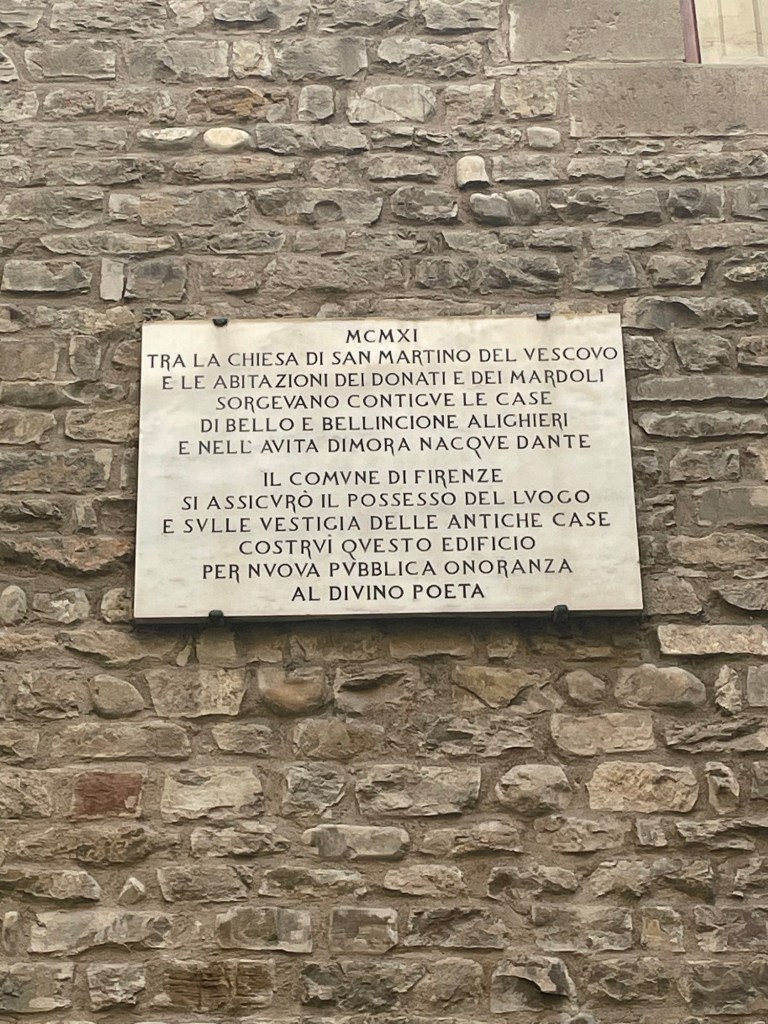

There’s no mistaking the fact the Florence and Ravenna tourist boards seek to cash in on his legacy. In Florence many streets bare engravings from the Divine Comedy and there is now the Dante House Museum on a site estimated to be near his home, though the exact location remains unclear.

Opposite the museum is the Church of Dante which belonged to the Portinari family where his unrequited love, Beatrice, was married to another man.

Today, lovers tie love locks and tuck heartfelt pleas and into the folds of the doorway wishing for a love that would take them to the stars and back, as Dante’s did.

As I trace Dante’s steps to Ravenna this question of the location of his remains will be in my mind.

I avoided the busy central Piazza del Duomo because I wanted to preserve my impressions for when I would meet Alina, my former Ukrainian student, tomorrow to start the Dante trail.

At a bar by Ponte Vecchio I got chatting to a charismatic English woman who had also travelled to Florence on her own for a get away between jobs. We quickly struck up a rapport and discussed all things ‘being in our 30’s and not having kids’, the wave of our friends who had bought up town houses in Tottenham to start their families while we indulged in our freedom to sip on a glass of something bubbly at 4pm in the sun and contemplate the relative physiological merits of the stream of tourists who passed.

‘Oh if you’re looking for Italian men you’re on the wrong spot.’ The waitress informed us as she used her tea towel to chase away the pigeons. One, she informed us, was called ‘stumpy’ because he’d lost his feet perching on one of the many anti-pidgeon contraptions that line the city’s window ledges. The real Florentines live across the river, she continued.

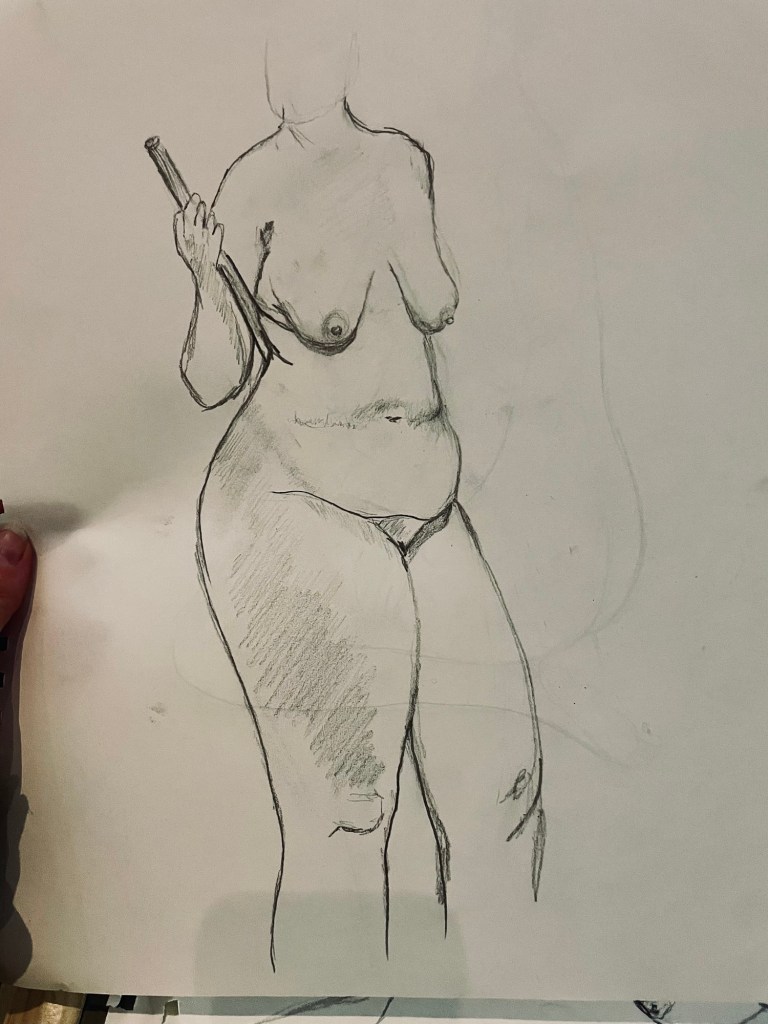

It was across the river I proceeded to the British Institute in Florence. It was Monday night and I knew instinctively upon my arrival that I was to spend the evening indulging in a familiar past time of life drawing at Sotto Il British. The class is lead by Tom J. Byrne, a friendly Irish man with a walking stick. He remarked that I looked familiar.

‘I used to come here all the time when I lived in Florence,’ I reminded him.

The British Institute is a magnificent building that houses a speculator Oxfordian library with comfy chairs that point out towards the river.

The model was a beautiful young woman who took to the various 5 minute and 15-minute poses with ease. A well-dressed lady of middle age – you know the type, flowing fabrics and a well sized pendant on an embellished chain – sat opposite me with her small brown dog at her feet using watercolour and ink to capture the model’s Rubenesque curves.

As always, the talent of the artists was at once intimidating and deeply compelling and I took pleasure in sketching my own humble contribution. Drawing together it felt like we were part of an orchestra.

The model rewrapped herself in a pastel blue robe and I took leave of the nibbles and wines and headed back to Santo Spirito where I was to spend the night with Anna, a Finnish-British jewelry maker who has made her home in Florence for most of her adult life.

I had met her when I was living in Florence at the Santo Spirito market where she was selling her stunning range of goddess themed amulets and earrings. Citronella, garnets, emeralds, all crafted into a range of designs in bronze and silver. Mermaids, the sun goddess, Durga. I immediately fell in love with her work and also her friendly demeanor.

Anna had that beauty about her that many women in their 60’s do – natural hair tied loosely into a bun and a velvet shawl. She introduced me to her daughter Elena who was wearing a stunning lapis lazuli pendant her mother had made for her in the same way my mum makes quilts for me.

The goddess’ sinuous body was curved round into a circle with her breasts gilded in silver. Elena was a beautiful as the necklace. Long blonde hair to her waist and bright blue eyes to match the pendant.

Lapis lazuli has been my favourite stone since I went to India at the age of 15 and purchased my first piece with my pocket money. I was mesmerized by the deep sea blue and iridescent gold mottled together in a divine harmony – to gaze into a piece of lapis lazuli is akin to gazing into the night sky. It is infinite.

Lapis lazuli comes largely from Afghanistan. An Afghan friend once told me that there is a piece of Afghanistan in every Renaissance painting in the veil of the virgin Mary who is often depicted in blue pigment – the most expensive at the time. For my part I carry a stone on my finger gifted to me during lockdown by my dear friend, Xiren. It’s a big as my thumb and dominates my hand. I enjoy watching it sparkle as I type.

I dined that evening with Anna, her husband and daughter, a simple but delicious fare of broccoli pasta with chilli and pink salt from Bhutan from where Anna and Elena had recently returned impressed by the state of calm afforded by the Buddhist majority. I was a bit late due to my art class so I ate at a beautiful table set up by Anna in their jewelry workshop with a candle and a table cloth – in Italy all meals must be enjoyed with a table cloth.

We discussed all things alternative medicine – Anna has recently published a book which I edited on the divine herb Artemisia which has healing properties and is revered around the world.

We slept together in the small studio which was decorated with lapis blue walls and depictions of goddesses in various states of trance, Anna, her husband and daughter on sleeping mats and me on the sofa. Anna slept in a stunning Moroccan jellaba the colour of the deep green sea.

Recommended Reading: The Divine Artemisia by Anna Lord: https://www.amazon.co.uk/divina-artemisia-Anna-Lord/dp/B0D329DQJV

Recommended Watching: Reading Dante with Refugees: An Introductory video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHOeh2w9FdI

Recommended Reading: OpenDemocracy 50.50 Our Africa: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/tagged/5050-our-africa/