I had an easy day, retracing Dante’s footsteps as a political exile who had a tumultuous relationship with his native Florence.

My sleep was disturbed and, as I was sharing the dorm with an Italian couple from Bologna, Giuliana and Vittorio who had arrived late the night before, I finally made use of my pink EarPods to listen to some sleep hypnosis meditations.

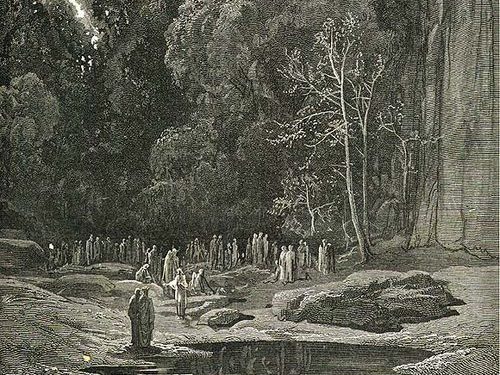

I had fevered dreams and was reminded of Dante who in canto 27 of Purgatorio passes through the wall of flames to Paradise, only to collapse with sleep with his guides, Virgil and Statius at his side:

‘Before one color came to occupy

that sky in all of its immensity

and night was free to summon all its darkness,each of us made one of those stairs his bed:

the nature of the mountain had so weakened

our power and desire to climb ahead…From there, one saw but little of the sky,

but in that little, I could see the stars

brighter and larger than they usually are.But while I watched the stars, in reverie,

sleep overcame me—sleep, which often sees,

before it happens, what is yet to be.’

But as Dante wakes eager for the journey ahead, writing,

‘my will on will to climb above was such

that at each step I took I felt the force

within my wings was growing for the flight’

I, on the other hand, was exhausted.

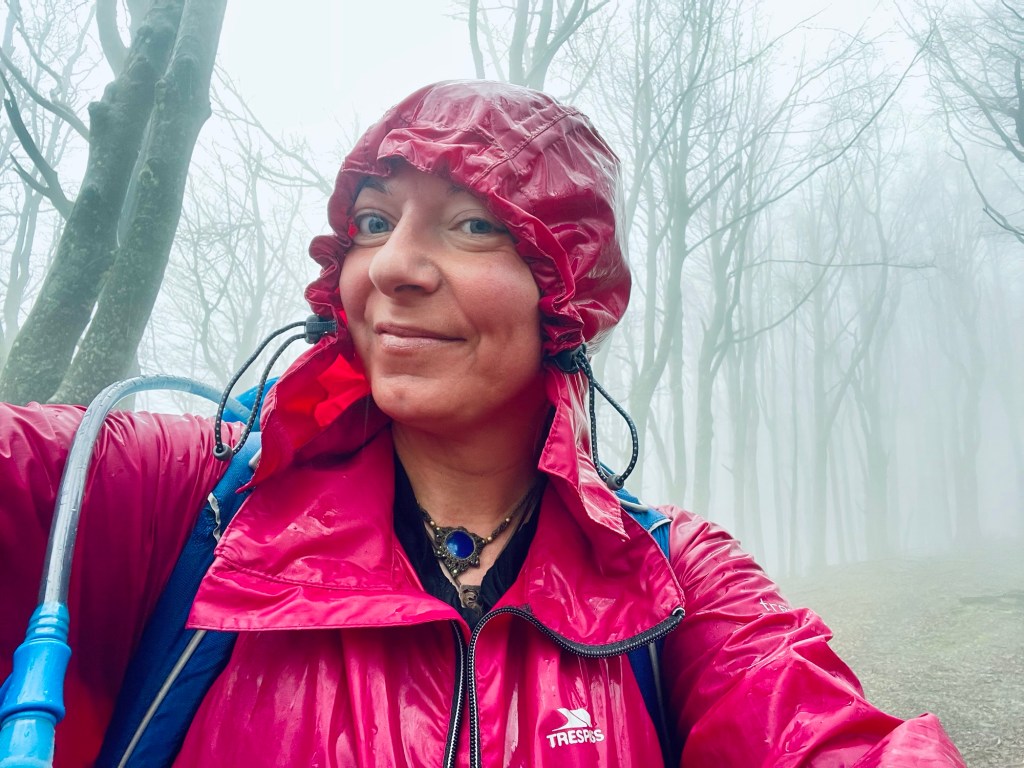

Because of a landslide, I would have to retrace yesterday’s steps and take a longer improvised route round to San Godenzo.

Over a breakfast of sweet pastries, the hostel owner Gian Luca suggested I miss the first part and start back on the trail from after the landslide.

I didn’t need much convincing, so when Vittorio offered to take me halfway in their car, I agreed.

It would give me more time to catch up with work, specifically, a funding application I was developing to read Tagore with refugees in India. In one of his most beautiful poems in the collection Gitanjali, he describes a world undivided by borders:

‘Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.’

It would be fascinating to see what refugees made of the world of this cosmopolitan Nobel Prize winning author. After Dante, Tagore was one of my favourite poets.

‘Many people take public transport as they don’t manage after yesterday’, said Gian Luca reassuringly before he headed to the kitchen to make pasta for that day’s meal.

In the car, Giuliana and Vittorio told me a little of their work in music and events.

Soon we had arrived at Passo da Muraglione where Gian Luca had indicated to them to drop me but it turned out it was the wrong spot and I was completely off the Dante trail. I couldn’t ask the couple to drive me back another 30 minutes, and so I graciously accepted their offer to drop me directly in San Godenzo where they were passing through instead. From there it would be a three kilmetre walk up to the Agriturismo I had booked. I’d get a few steps in but the day would be my own to rest and recuperate.

The car sounded out gospel tunes and many motorcyclists sped past on the road.

‘It’s the Spotify algorithm’ explained Vittorio. He’d liked one hymn and now the internet had decided he was religious.

In San Godenzo, I invited my hosts for a coffee and I had a slice of pizza, unsatisfied, once more, with my sweet breakfast. It was 10.30am.

I saluted the friendly couple and made my way to the abbey of San Godenzo in Piazza Dante Alighieri where the poet-politician had met with Ghibellines and White Guelfs in his first months of exile in June 1302 to try to forge an alliance against the Black Guelfs who had expelled him from the city.

The convention brought together the noble families who were expelled from Florence and wanted to plan their return to the city by meditating on revenge. Dante’s name is signed in the attendance list.

Walking around the abbey, I felt Dante’s political presence. I thought of all the refugees I knew who were committed to activism across borders. My friend Javid campaigned for women’s education in Afghanistan while an Albanian youth group I had worked with had started a campaign against blood feuds.

Although the 1302 convention did not lead to action, for more than 30 years, San Godenzo has commemorated this event during the ‘Dante Ghibellino’ festival, with a historical procession through the town streets. The celebrations culminate in awarding the homonymous prize to citizens who, during the year, have distinguished themselves for their civic commitment to San Godenzo, its territory and its community.

As a political exile, Dante was excluded from a Florentine pardon in 1311, but another amnesty in 1315 would have allowed him to return. Unwilling to comply with the terms of the offer—admission of guilt and payment of a fine—Dante was again sentenced to death, this time by beheading rather than fire, the penalty now also applying to his sons, Pietro and Jacopo.

An additional provision stated that anyone had permission ‘to harm them in property and person, freely and with impunity.’

Dante’s refusal reflected not only his great pride but also his better living conditions. While the first years of his exile had been brutal, by 1316 he was now residing in Verona as a guest of the Ghibelline ruler Cangrande della Scala. Having cut ties with his native city, he declared himself ‘Florentine by birth, not by disposition.’ Dante had learned how bread outside Florence ‘tastes of salt,’ but such bread was also not lacking as he sought out more abundant hospitality towards the end of his life.

Dante’s ‘overswollen pride’ is reflected in the significant time he spends with the proud in Hell and on the terrace of the proud in Purgatorio. Indeed, Dante presents pride as the foundation of sin by situating it at the base of Mount Purgatory.

In Purgatory, he walks alongside the proud souls who are forced to carry heavy loads:

‘I, completely hunched, walked on with them….for such pride, here one pays the penalty’

Dante then reflects on the fleetingness of reputation and fame:

‘O empty glory of the powers of humans!

How briefly green endures upon the peak-

unless an age of dullness follows it…Worldly renown is nothing other than

a breath of wind that blows now here, now there,

and changes name when it has changed its course.’

There is an irony here, since Dante is also explicit about his desire to bolster his reputation through the written word.

In Inferno, meanwhile, one of the most realistic conversational exchanges occurs between Dante and Farinata degli Uberti, the great Ghibelline leader in the battle of Montaperti, who died the year before Dante’s birth. Farinata is depicted in ‘the cemetery of Epicurus and his followers, all those who say the soul dies with the body.’ However, he is also guilty of the sin of pride, something we see through his rising out of a burning coffin, stubborn and defiant.

‘My eyes already were intent on his;

and up he rose—his forehead and his chest-

as if he had tremendous scorn for Hell.’

Dante uses the meeting to discuss Florentine politics, engaging in vocal sparring. Farinata immediately recognizes Dante as a Florentine citizen from his accent:

‘Your accent makes it clear that you belong

among the natives of the noble city

I may have dealt with too vindictively.’

He then goes on to explain how he was responsible for the exile of many of Dante’s ancestors`:

‘When I’d drawn closer to his sepulcher,

he glanced at me, and as if in disdain,

he asked of me: “Who were your ancestors?”Because I wanted so to be compliant,

I hid no thing from him: I told him all.

At this he lifted up his brows a bit,then said: “They were ferocious enemies

of mine and of my parents and my party,

so that I had to scatter them twice over.”’

While there is certainly no love lost between Dante and Farinata, there is a measure of respect. Farinata, called magnanimo, ‘great-hearted’, put Florence above politics when he stood up to his victorious colleagues and argued against destroying the city completely.

‘But where I was alone was there where all

the rest would have annihilated Florence,

had I not interceded forcefully’

As the literary critic Auerbach has noted, Dante’s realistic and somewhat flattering depiction of Farinata shows his willingness to admire and work alongside his adversaries, something he did by uniting with the Ghibellines during the 1302 convention in San Godenzo.

Dante rebuffs Farinata’s insults by boasting that on both occasions when his ancestors were exiled, they returned:

‘“If they were driven out,” I answered him,

“they still returned, both times, from every quarter;

but yours were never quick to learn that art.”’

The art referred to here is the art of exile. As Barolini explains, the above conversation references four cataclysmic events in Florentine politics of the thirteenth century, as Florence oscillated between Guelph and Ghibelline control until the ultimate defeat of Farinata and the Ghibellines at the battle of Benevento of 1266.

In effect, the dialogue lays out two sets of factional routes and returns. The first set of route and return comprises the 1248 defeat of the Guelphs by the Ghibellines, with the help of Emperor Frederic II, followed by the return of the Guelphs in 1251, after the death of the Emperor.

The second set comprises the 1260 defeat of the Guelphs by the Ghibellines at the battle of Montaperti, where Farinata led the Ghibellines to victory with the help of the Sienese and Manfredi, Frederic’s successor, and then the subsequent defeat of the Ghibellines and return of the Guelphs following the battle of Benevento and the death of Manfredi in 1266.

The abbey where Dante convened with Ghibellines of his own day featured a plaque to honour him and some stunning mosaics that had been added some time after he had congregated there.

Outside the church someone had hung a banner saying, ‘possesion isn’t love.’

I walked for half an hour up a hill to the Agriturismo Tenuta Mazzini where I was met by Filippo, the son of the owners who was out foraging for strigoli. He was walking alongside a woman carrying a wicker basket. Strigoli, or stridoli, are a spontaneous grass typical of the Tuscan-Romagna territory. The name comes from the screeches that two leaves emit if rubbed together. It is edible and often used in risotto or salads. It’s especially tender at this time of year, explained Filippo.

There was a sign forbidding people from collecting mushrooms and chestnuts between the 1st of September and 31st of October but there was no mention of harvesting grasses. What’s more, the seasonal ban had yet to come into force.

Filippo showed me where there was a local restaurant that served lunch, but the owners had provided spaghetti, tuna and tomato sauce so I made myself a meal that would serve as both lunch and dinner.

The apartment was spacious with a comfy double bed, quite a welcome contrast from yesterday’s basic amenities and a total bargain at just 45 Euros a night. There was a poster by Matisse and a copy of The Two Cherubs by Rafael from 1513. The latter is part of a bigger painting that features the Madonna holding the Christ Child, flanked by two saints. The figures are placed among the clouds, suggesting that it is a scene from heaven. At the base of the painting are the two winged cherubs, looking up at the scene from below.

Outside there was a swimming pool that was overhung with wisteria. It boasted a view of the rolling hills. I watched as a nuthatch flitted from branch to branch then disappeared into the distance.

A lady staying in the flat next door, Cristina, had brought six cats with her and took them each out for a wonder on a lead. Milu was among the friendliest and we shared caresses on the grass.

As I caught up on work, including meeting online with my PhD student Olivia who was doing research on asylum seekers’ reception in UK hotels, I recalled Dante’s words about how writing is a way to ‘make oneself immortal.’