On my final day, I met a lovely couple who invited me for lunch and felt the warm embrace of the sun and of friends which filled me with new life.

I slept badly, waking up every two hours. I was worried about my broken toes and how they’d manage the 21 kilometres I would have to face to make it back to Florence and complete the ring of the Dante trail. The very prospect had seemed near impossible when I had shared my wish with Massimo Kyo and Alina in the tranquil oasis of San Pietro a Romena two weeks ago, and then again two days ago in the Hermitage of Santa Maria. Now I was so close and the end was in sight. Yes, I was doing it.

I tried to summon up Virgil’s words of encouragement to Dante in canto 24 of Inferno when he becomes weary as they pass through the bolgia of the thieves:

‘“Now you must cast aside your laziness,”

my master said, “for he who rests on down

or under covers cannot come to fame;and he who spends his life without renown

leaves such a vestige of himself on earth

as smoke bequeaths to air or foam to water.Therefore, get up; defeat your breathlessness

with spirit that can win all battles if

the body’s heaviness does not deter it.A longer ladder still is to be climbed;

it’s not enough to have left them behind;

if you have understood, now profit from it.”’

I would rise up like Dante and take on the steep climb up to the Convento dell’Incontro:

‘Then I arose and showed myself far better

equipped with breath than I had been before:

“Go on, for I am strong and confident.”’

On my way out of the town at around 9am I stopped momentarily to watch a tall man pruning an olive tree on a ladder. It was a sunny day, perhaps the sunniest so far on the cammino. Despite this, I wore my long-sleeved black top in order to protect my new tattoo from the rays. The purple stencil had already started to disintegrate rendering the terracotta outline clearer. I loved it.

I went down the hill past the beautiful medieval bridge that had been damaged in the recent floods and stopped at an old bakery to purchase some pizza and fizzy water. The streets were bustling with people and, despite my fatigue, I found myself whistling in good cheer.

I passed a police officer who was giving a black man a car ticket and saluted Asia who I had met the previous evening in the tattoo parlour. A swallow flew inches from my face as I passed under the bridge which was cluttered with antique furniture. It looked like everybody was spring cleaning. There were up turned stools, desks devoid of drawers. Two sagging single mattresses framed the display on either side like columns.

It was nice to be walking along the river. The fresh graffiti contrasted with the muted tones of the brick walls. A man passed with a shopping trolly and a flight of joggers zig-zagged along the narrow path. I thought back fondly of running along the river Charles when I had lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and hoped that my foot wouldn’t give me too much bother so that I could be up and running myself again soon.

To the right of the path was a sculpture of a man striding forth from a rock. I was reminded of the engravings that Dante sees on the terrace of the proud in canto 10 of Purgatory which are so lifelike that they seem to speak to him of acts of humility:

‘There we had yet to let our feet advance

when I discovered that the bordering bank—

less sheer than banks of other terraces—was of white marble and adorned with carvings

so accurate—not only Polycletus

but even Nature, there, would feel defeated…This was the speech made visible by One

within whose sight no thing is new—but we,

who lack its likeness here, find novelty.’

Thus was the power of great art.

A sign said ‘no fishing’.

Two men were fishing.

The water ran aquamarine.

I was saluting everyone on the path, including a new mother who was stroking her baby’s fine hair on a picnic blanket beside the river. The hawthorn petals were a perfect white and exuded an almond-like perfume.

The recreational path soon gave way to allotments which featured a variety of vegetables and flowers that were being carefully attended to by a diverse group of local citizens. It was the first time I’d seen yellow irises, and here was a line of Romagnolo artichokes in their characteristic bruised purple and green.

I crossed the river over an iron bridge. The pathway was perforated with little holes so that you felt you might fall down at any point. It reminded me of being scared, as a child, that I would slip between the staggered metal stairs at the council flats where my school friends had lived back in Milton Keynes.

I was slightly haunted by the size of the hill ahead of me and though it was only 10:15am, I was already hot.

I stopped to check directions with a man who was cutting grass. It looked like he’d put henna on his hair the way some older Indian men do. It was a livid orange.

The yellow broom smelt buttery and delicious.

I passed a church on the right and took a wrong turn which afforded a beautiful view back over the city. I then retraced my steps to take the steep climb of the wooden bank off to the left of the road. The foliage was intruding onto the path in thick tendrils causing me to duck and dive. A spider web was suspended in the sunlight, diaphanous.

I could feel the weight of not having slept with every step up the woodland pass but the shadow of the trees was merciful. I was rewarded by the sight of a kaleidoscope of tiny flowers. Here some purple gromwell creeped along the ground, sending out long trails of dark green matt leaves sprinkled with gentian-blue flowers. And there were pink prongs of common sainfoin. I recalled how Dante described being drawn to beauty in Purgatorio, canto 18:

‘The soul, which is created quick to love,

responds to everything that pleases, just

as soon as beauty wakens it to act.Your apprehension draws an image from

a real object and expands upon

that object until soul has turned toward it;and if, so turned, the soul tends steadfastly,

then that propensity is love—it’s nature

that joins the soul in you, anew, through beauty.’

As I exited the woods, I passed a tennis court which seemed unusually located on the rocky terrain. Two men were working out how to get a van along the path. The one who seemed to be in the more authoritative position was wearing blue overalls. Now it was nearly 12 o’clock and the sun was beating down on me. Soon I’d stop for my lunch of the remaining pizza.

But I didn’t have pizza for lunch after all. Instead, I chanced upon Matthew, an English man from Derby, near where I live, who was outside his house performing chores. His sweet dog Paloma had come to greet me and when I’d saluted her back in English, Matthew asked me if I’d like some water.

I gratefully accepted.

And this wasn’t just water, it was fizzy water – ice cold and from a Soda Stream.

We soon got deep into conversation about all things Oxford where he’d also studied, and rowing, which I had not, and, with that, conversation turned into lunch.

Matthew was an environmental engineer while his Italian wife, Nicoletta, who he’d met at language school, worked in fashion. Florence in the summer was too busy for them with tourists, they said; they liked their hillside retreat. I was reminded of summers in Oxford when I would angrily ping my bell as foreign exchange students would stray into the cycle lane. I had been so lucky to live in Florence during the winter when the whole city had felt manageable and somehow my own.

Nicoletta had prepared a delicious quiche and focaccia which we ate with a salad and local pecorino cheese.

‘I’d offer you chedder, but that seems unfitting,’ Matthew quipped.

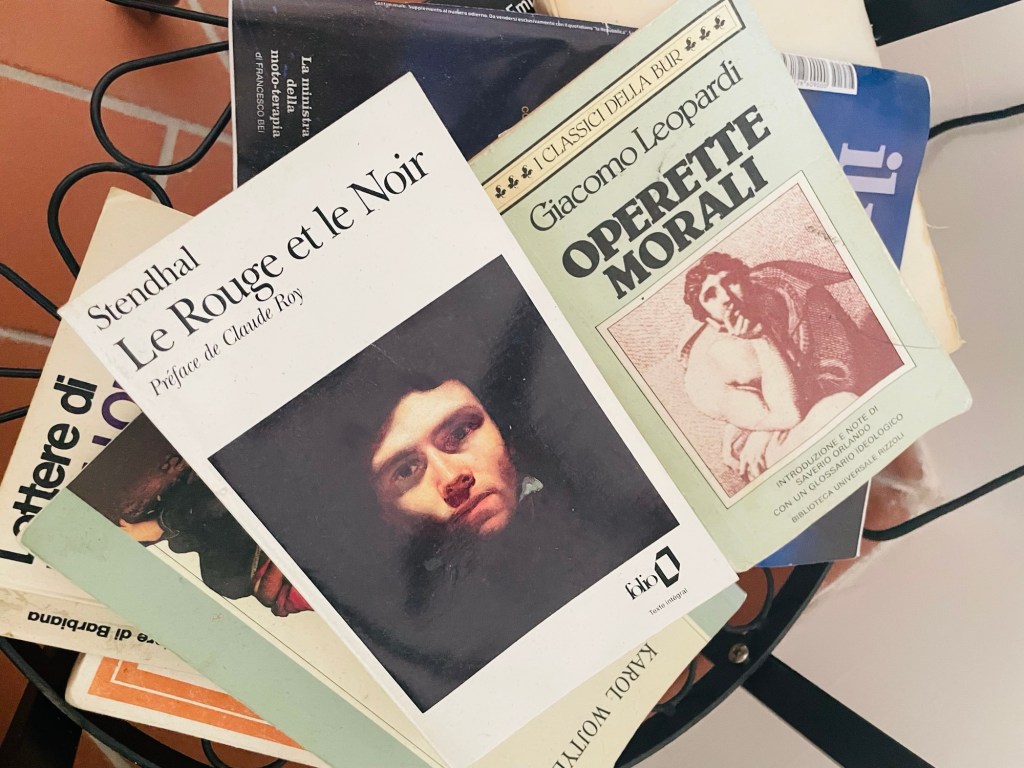

As I told them about my journey, I noticed that Nicoletta had tears in her eyes. She was a fellow Dante aficionado and was deeply moved by the fact that I had embarked on this pilgrimage. We began citing Lorenzo di Medici’s famous poems, finishing the sentences of one another:

‘How wondrous beautiful is youth,

yet fleeting, so soon gone, in truth!

He who will, let happy be,

The morrow has no certainty.’

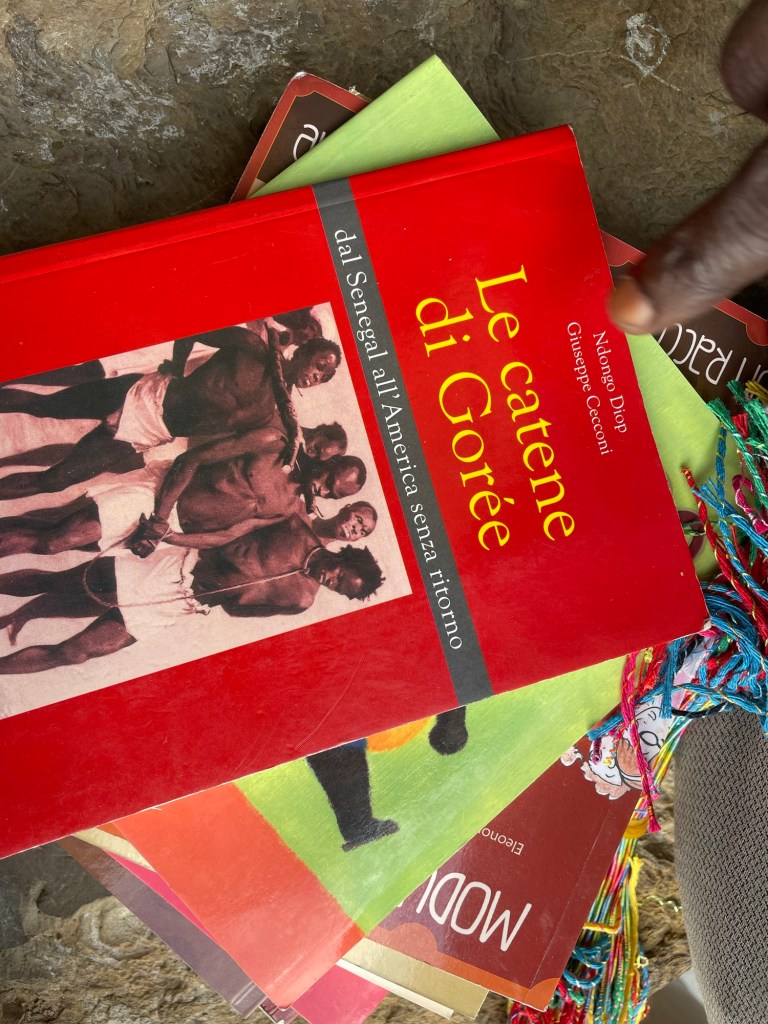

I told her how instead of the Backstreet Boys I’d had a poster of Lorenzo di Medici on my wall as a teenager. She could relate. She explained that she’d just got round to unpacking a box of books including a compendium of Italian verse which she was devouring.

There was a princess crown in a bowl with walnuts that belonged to their daughter who was named Florence Rose. They had lived in the house three and a half years and done a spectacular job of restoring it. It even had a bathtub! How very unItalian, came my immediate thought.

Their ample garden was rich with almonds, walnuts, figs and cherry sized plums. There was a peach tree that Matthew had just planted beside their pool and rows upon rows of olive trees from which they harvested their own oil. The key to pruning them, Matthew explained, is to hollow out the inside so that the tree looks like a donut. I thought about my own short-lived time as an apple tree pruner on a farm in California. How I had romanticized and then so quickly come to detest that slow labour.

I spent about an hour with Mathew and Nicoletta sitting on sunbeds by their pool chatting leisurely. Then, I took my leave, explaining that I had friends who would be waiting for me in Florence that evening.

‘You must come back!’ said Nicoletta as I heaved back on my rucksack and headed down the dusty drive. I very much hoped I would.

After a steep ascent up to the Convento dell’Incontro, I got my first sight of her. There she was before me once more with a skyline woven in orange thread: Florence, the most beautiful city in the world. There was the Duomo, San Lorenzo and Giotto’s tower. And there, somewhere in the hazy distance, were Alina and Kelsey who had travelled specially to Florence to meet me at the end of my cammino.

I thought I’d better get a move on, but at the same time something about today made me cherish each individual step. I was slower on foot not because of my broken toes, but because this was my last day of a three week long cammino and I knew how much I’d miss the tread.

I didn’t put on an audiobook or music, I just wanted to be at one with my thoughts and reflect on what I had achieved: the highs and the lows, literally and metaphorically.

A fellow hiker who looked North American was walking the other way. I saluted her – she was as pink as I was in the afternoon sun. I noted that one of the cuts on my hand might be infected and applied some ayurvedic balm. A bright green caterpillar dangled on a thread.

The descent was without shadow, a combination of brushland and road. I breathed in the sweet scent of wild sage as sweat accumulated in my philtrum and then spilled over onto my lips. I could hear the blood pumping in my ears. I couldn’t imagine doing this hike in the summer months.

I was trying to walk on my heels as much as I could as the pain in my toes grew more insistent.

With each corner, Florence emerged again in all her splendor, framed by a variety of species of trees. I thought of Dante’s poem ‘Three women have come round my heart’ which he wrote from exile, longing for a view as close as this.

‘They each seem sorrowful and dismayed,

like those driven from home and weary,

abandoned by all, their virtue and beauty

being of no avail.

For though we are wounded now, we shall

yet live on, and a people will return

that will keep this arrow bright.

And I who listen to such noble exilestaking comfort and telling their grief

in divine speech, I count as an honour

the exile imposed on me; for if judgement

or force of destiny does indeed desire

that the world turn the white flowers

into dark, it is still praiseworthy to fall

with the good. And were it not that the fair

goal of my eyes is removed by distance

from my sight – and this has set me on fire –

I would count as light that which weighs on me.’

With each careful step I was just that bit closer to San Giovanni where I would lay my rose from Ravenna at Dante’s place of imagined return. It had gone a bit moldy in my bag if truth be told but it was the thought that counted. And over the last three weeks I had given this important step of my literary pilgrimage a lot of thought indeed. I was nothing if not a terrible romantic.

I had prepared well for the trip, but had I prepared myself for it to end? What would I do without that familiar sound of the cuckoo and the butterflies dancing before me along the path? The pretty purple wildflowers and all those hundreds of barking dogs?

Florence felt so near that it was as if I could reach out and touch her, but she was still 10 kilometres away. I passed a shrine that someone had embedded in a tree and took a moment to make a wish before spontaneously embracing it. Then I stopped for a little rest.

I reached the first open bar at around 3pm and delighted in downing some more fizzy water.

Then, after half an hour more, I’d reached the river Arno. It looked like reflective glass. I thought about Giordano and his Monet Lake made out of mirrors. Anna, Massimo Kyo, Rossella, Enrico, Oliver, Paulo – what people I had met on my way!

I passed a hedge of Japanese cheesewood whose flowers smelt citrusy and vibrant. I took a sprig and held it to my nose, inhaling every last hint of perfume. I picked some wild garlic and smelled the oil heavy on my hands. There was so much here you could make a whole batch of pesto, I thought.

I was getting into the suburbs now. I passed the Florentine Equine School and a Business Centre for Young Doctors which had a crest decorated with half of the Florentine lily and half of the Medici shield.

The landscape had flattened out and I heard children playing in a schoolyard. It was strange to use a zebra crossing and be amongst so many cars. I was now just over 90 minutes away and would reach the baptistry by five.

I caught sight of myself in one of the corner mirrors on the road. I hadn’t washed my hair in five days and my braids were fraying at the edges. But I looked well. I looked really well. As Dante had written over 700 years ago, this was a ‘vita nuova’, a ‘new life’!

As I traced the path along the Arno, a form of blossom like sheep’s wool collected at my feet, causing me to sneeze. Some people were sunbathing next to the weir. I remembered running up there in those precious three months I had spent in Florence as a Visiting Professor. Someone was sitting on a plastic chair in the middle of the water, of course. A lone woman was kayaking down the river.

I kept my eyes peeled, recalling the time I’d taken the group of refugee students to Florence and my co-facilitator, Mortezza, had spotted an otter in the bullrushes.

‘It looks just like the emoji!’ Mihal from Venezuala had exclaimed.

I’d also spotted kingfishers several times.

I retraced the path of the beginning of the cammino which I’d hiked with Alina at my side, recalling the same beehives, hens and the same random upturned table in the middle of a lawn.

My inner world had changed profoundly and my outer body too – I had thick calves and my behind seemed to have moved up an inch. But here much was the same. A young woman in fashionable sunglasses walked past me with a Calvin Klein bag; another woman with neon pink lightening earrings rode by on an electric scooter. Two female lovers sat opposite one another on a bench with their legs intertwined.

And now I was in the city in earnest. The dum dum dum of music with a heavy base played out from somewhere to my right and several joggers ran topless in the sun. Tour coaches lined the streets with signs reading promises such as ,’Experience Pisa and Florence in a Day.’ I stopped to observe a lizard biting another’s tail.

‘Have you come far?’ asked an elderly gentleman.

I had, I replied.

‘Porca puttana miseria’ came his response, ‘good for you!’

I passed the canoe club and the bridge off to Piazza Michelangelo from where, on several occasions, it had been a delight to watch the sunset. I passed through the remnants of the old city walls.

Florence had always seemed like such a small city to me, but suddenly it seemed so big.

Here and there were grids covered by the familiar ugly orange netting. But now it didn’t mean that there had been a landslide, it meant roadworks.

Two people walking with audio guides around their neck nearly walked into an open drain as they passed a stall selling suggestive aprons stamped with the statue of David.

I didn’t need a map now. I was on home turf.

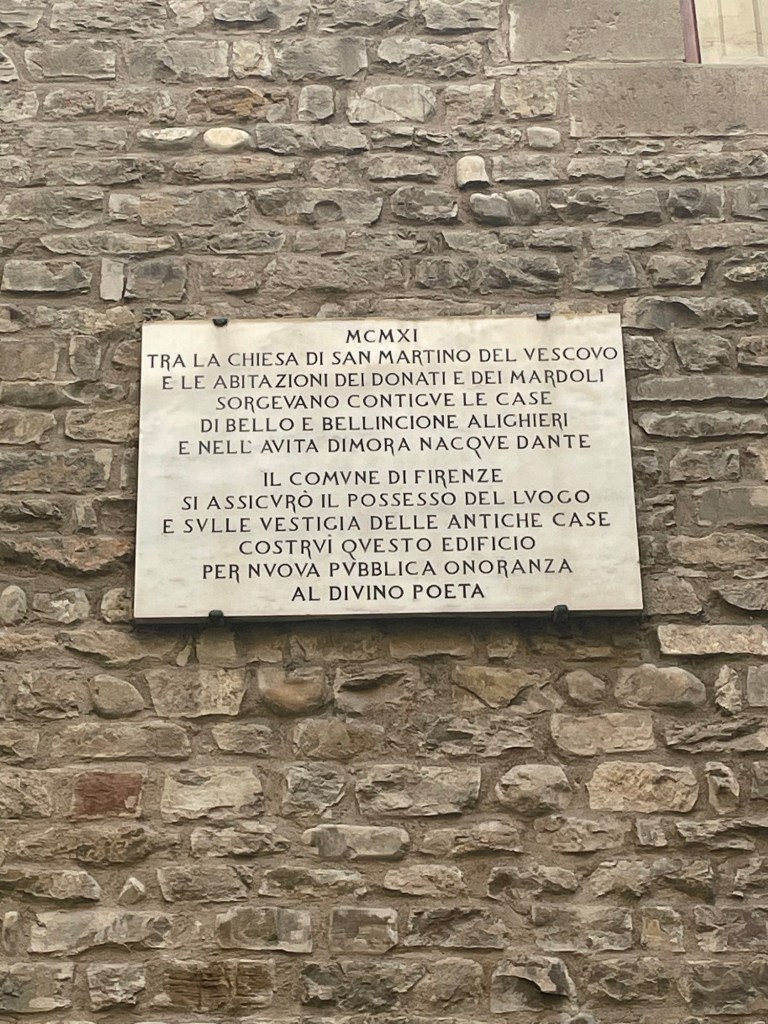

I passed the national library with its Dante sculpture and quote from his political treatise Convivio, ‘let this be new light’. Then came the Galileo Museum, shortly after which I turned right at the Uffizi galleries. Over the heads of all the eager street artists, I spied a second Dante sculpture which depicts him pointing at himself in a gesture of self-importance and pride. Here in stone, he has been bequeathed the laurel crown of poet that he so desperately wanted to return to wear in person before he had died, aged 56, in exile. I thought of his bones, lying in Ravenna.

From Palazzo Vecchio I weaved in and out of guide groups who were following umbrellas of every neon hue. Three people were eating the special Florentine schiacciata on the move. A little Canadian girl was playing with a wooden sword.

‘Whoosh,’ she cried out, ‘off with their head!’

Under the stone arches, it was nice and cool. But I’d never been here when it had been so busy. It was heaving.

The smell of leather hit me as I passed down the main street and I resisted the temptation to pop into my favourite lingerie stores. I couldn’t believe I was in reach of the baptistry, my final stop.

I was glad to have this final moment on my own. The last three weeks had tested me beyond what I thought I could endure physically and mentally and I felt happy and restored.

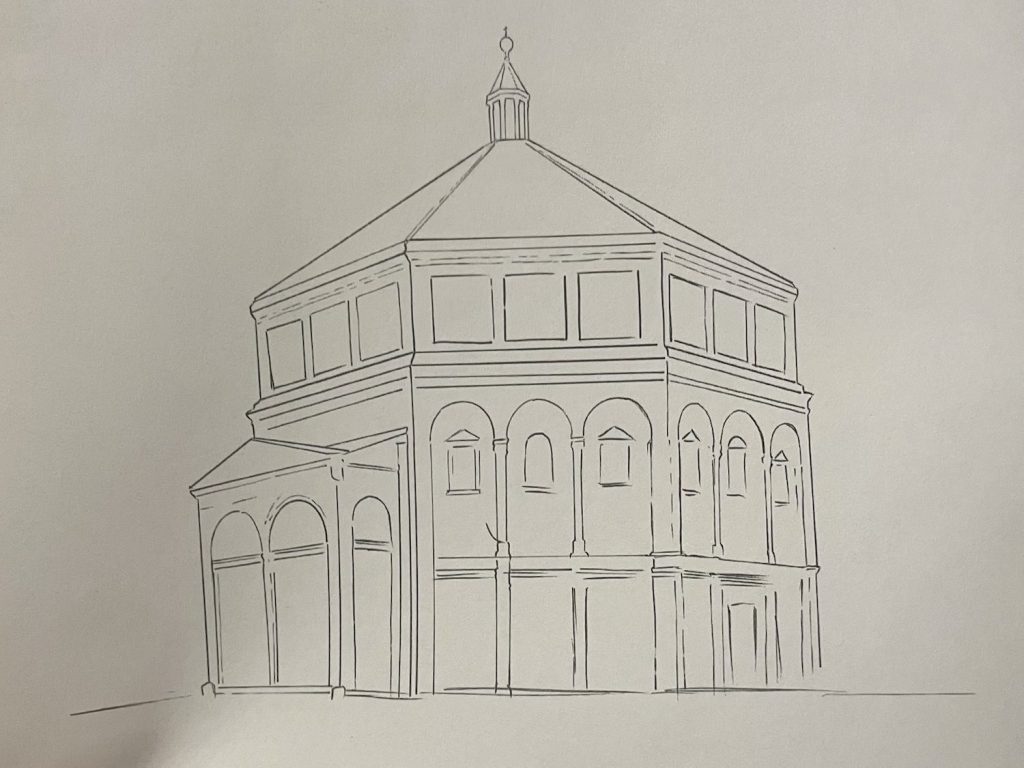

And with that, I turned the corner and there she was, the baptistry in her green and white marble.

She stood simple and sublime.

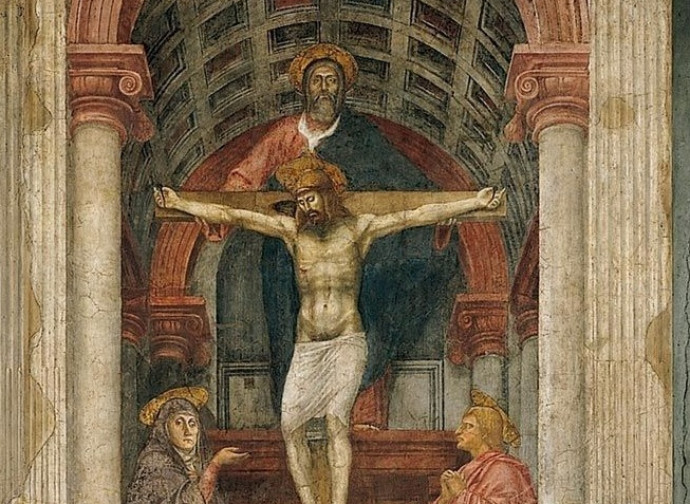

I thought of how struck I had been at the age of 15 when I had first seen the mosaics inside and of the copy of Christ’s head that I had rendered that was likely still situated in the paving of my old secondary school. I thought about the first time I had read the words of Dante and felt seen and understood in my sense of being lost. The sobs immediately came. I placed my hands upon the flank of San Giovanni and tucked the rose I had brought from Ravenna in the doorknob. Dante’s dream had been to return as a poet and now, in some ways, symbolically, I had brought him back.

Turning the corner, Kelsey and Alina with whom I’d shared parts of the cammino were there to greet me with a huge hug. Kelsey had made me a laurel crown with roses which she placed upon my head – they smelt magnificent. Alina who was wearing characteristically fashionable unmatching earrings squirted at me with champagne in the traditional fashion of Italian graduations. I sent a picture to Giordano, the founder of the trail.

‘Consider yourself a graduate of poetic passages in Tuscany and Emilia Romagna,’ he replied with a smiley face emoji.

That word passages had come to mean so many things to me. Passages of the Divine Comedy, passages through place and time; the many passengers who had travelled with me.

As I melted into Kelsey and Alina’s embrace I thought of canto 21 of Purgatorio when Virgil meets with his beloved mentor Statius and realizes that he is unable to hold him because he is but a shade. He says, in one of the most moving passages of the entire Divine Comedy,

‘“Now you can understand

how much love burns in me for you, when I

forget our insubstantiality,treating the shades as one treats solid things.”’

I had been gone three long weeks, much of which I’d spent alone in the wilderness, and as I hugged my friends, I felt my body return to life. I thought of all the times I had been to visit friends in detention centres where we’d been banned from touching; I thought of the borders that divided us; of Tagore’s ‘narrow domestic walls’.

Alina untangled her face from my hair.

‘A question’, she asserted.

‘Do you think, after all this, that Dante would have written the Divine Comedy had he never been a refugee like me?’