The way up was steep, but inspiring company and a delicious supper awaited.

I awoke at 2am to refuel the log burner in the community arts room where we were lodging and there followed a difficult but warm night of sleep. My day started at 7am when I rose to write and check work emails. It felt like breathing a new kind of air to have the time to write as the birds chirruped outside the window.

At 9am we were packed and having a breakfast of cereal and yoghurt with Stefano and his youngest son. My placemat read, ‘today is a good day to…love nature’. It felt prescient.

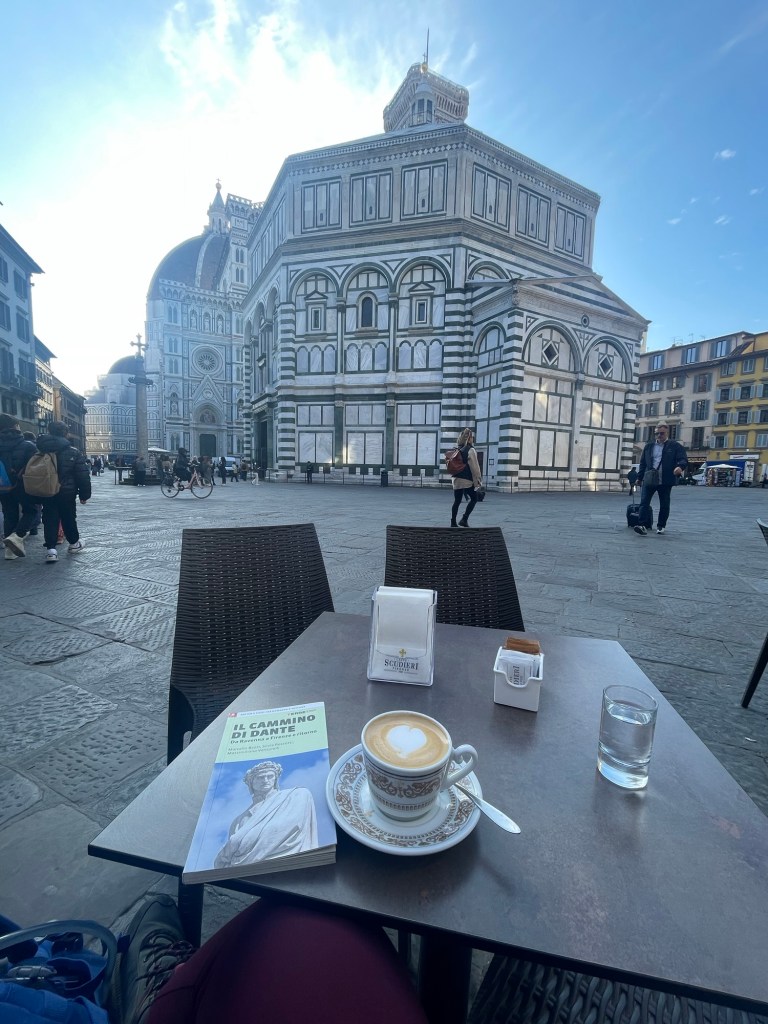

Alina and I said our goodbyes to our hosts and headed uphill for what was supposed to be a much easier day of the cammino.

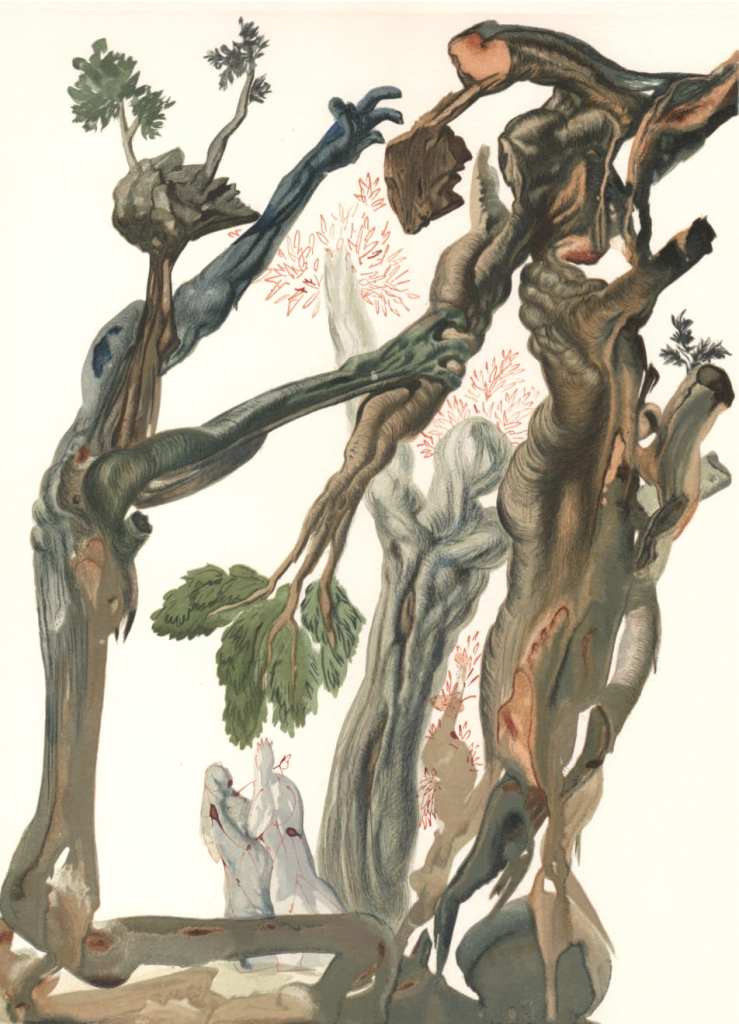

The sight of the church slowly disappeared from view as we climbed up the road which hugged sinuous vineyards. After yesterday’s experience and reflection on Dante’s wood of suicides, I found myself noticing each tree and wondering what kind of soul would be trapped within it. This one, here, with its gnarled roots and stubby fingers; and there, an oak with its sturdy frame.

Although the path uphill was quite straightforward, we missed a turning and ended up in the small, deserted town of Saltino (the official and much shorter route threads an arch to the side of it.).

The village appeared post-apocalyptic except for a bar where a lady with bleach blonde hair served us drinks – a cappuccino for Alina and an espresso macchiato for me. Alina introduced me to the song, Espresso Macchiato which is this year’s Estonian Eurovision song context entry.

‘Life is like spaghetti, it’s hard until you make it,’ sings Tommy Cash.

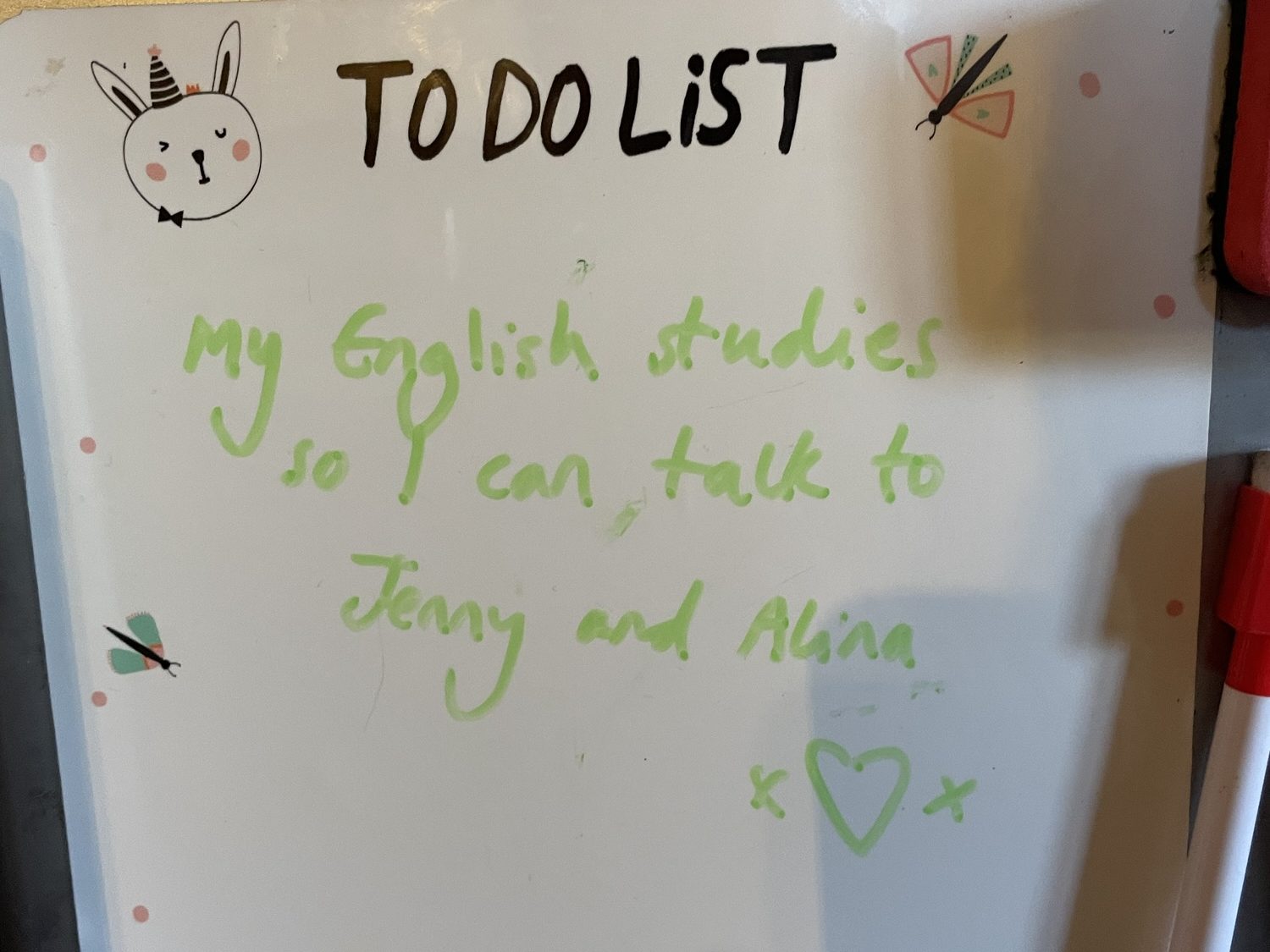

Eurovision has always been a big part of my life. I love the campness and the way that the heavy burden of nation states and regional strategizing is rendered playful, all accompanied in England by the teasing commentary of TV personalities Graham Norton and the late Terry Wogan. My sister-in-law, Jenny, is Swedish, and, in Sweden, Eurovision means business!

In recent months, after making a new year’s resolution to spend more time with my niece and nephew in light of the realization that I likely won’t have kids of my own, I’ve been driving the two hours in my blue Mini every month to visit them. This has included joining them in watching the Swedish nationals where viewers vote for this year’s entry. It’s a hyper produced show and luckily you don’t need to speak Swedish to enjoy it. I felt a stab of pride as my 12-year-old niece Louisa fluently translated the commentary for me. Oh, to be raised bilingual.

The winner of this year’s Swedish nationals who will travel to Basel, Switzerland for the competition in May is the Finnish band, KAJ, whose song, Bara Bada Bastu is about the joys of the sauna. It’s a catchy, extravagant number which will, for sure, give Estonia a run for its money.

Now here comes a fun fact I bet you didn’t know. Eurovision song contest entries don’t have to be from the country they represent. In 1988, Canadian artist Celine Dion represented Switzerland and won with the banger, ‘Ne partez pas sans moi’. Check out the video – she sports a tutu and a military jacket, quite the contrast to her sleek performance at the 2024 Paris Olympic Games (yes, I cried at it too).

I had the opportunity to travel to Finland myself in November last year during a research project for Save The Children on violence against children at EU borders. Between interviewing refugee children in reception centres, I had the pleasure of indulging in my own sauna experience. After singeing my skin red, I dived from Helsinki’s dock into the ice-cold ocean. Well, I say dive. In reality, I awkwardly and tentatively made my way down the metal steps until my body was under. Then my neck. Then my head.

Whoosh. The feeling was intoxicating, something between an orgasm and being burnt at the stake. I can see why the Fins are such a prosperous nation.

Saunas are such a big part of Finnish life that even one of the reception centres I visited had a sauna where a 17-year-old Colombian girl who was waiting on the result of her family’s asylum application told me she liked to spend time with her friends. I could imagine the Daily Mail headlines – ‘now SAUNAS for refugees!’ It made sense to me. It was freezing cold and in Finland, sauna equals life.

On our departure from the town up to Vallombrosa we passed a sign warning cars to slow down for migrating frogs.

The expansive abbey loomed over the surrounding landscape which included an empty water feature which was also signaled, ‘no fishing’. Italians in these parts seem to really like their public signs.

‘Sti Italiani!’ repeated Alina with her Roman lilt.

From there it was a steep climb up what seemed like one thousand stone steps which looked over one of several waterfalls we would cross today. Each corner of the cliff was marked by a little shrine.

At the start of Dante’s journey, he meets three beasts in the woods: a leopard, a lion and a female wolf that represent his fears. Readers have argued for centuries about what they signified for him – pride, lust, greed?

As we climbed, we distracted ourselves by discussing what our three beasts would be. Mine were fear of dying without realizing one’s talents and potential, perfectionism, and the terror that assails me from time to time that I might not be the good person people think I am. Alina is a Jungian. She reminded me, in a chastising tone, that ‘we all have shadow selves. Me, I can’t get enough of you.’

We are recording parts of our conversation as we walk for a future podcast since, to add to her already impressive portfolio of creative talents, Alina is currently studying sound design. As I adjusted my bra strap to ease the rub of my backpack, the portable microphone Alina had brought with her nearly went careering over the steep edge. Luckily it just fell a short way into the leaves where is disturbed a dozing lizard.

Alina and I have different body temperatures. I was sweating into my t-shirt, a gift from her which read Dante On the Move after our anthology of the same name, while she was wearing two jackets with a yellow jumper the colour of primroses tied around her neck like a scarf.

‘This was meant to be the easy day!’ exclaimed Alina.

We were rewarded with sweeping views across the surrounding hills. Then came the steep descent. It felt like we were walking down into Dante’s Inferno, each circle lined with ridges from which I could imagine Dante and Virgil looking down at the sinners below.

The sound of a stream accompanied our pilgrimage.

Animals have been a big part of our trip: we stop to pet every cat and salute every barking dog. But upon entering the town of Montemignaio we were greeted by two friendly sheep.

‘Salve!’ cried the owner who was walking them along a small lawn which was dotted with daisies.

‘Buona sera’ we replied.

‘Would you like to see where they live?’ asked the friendly lady. We did.

There followed an extraordinary evening.

First, Anna showed us the beautiful paddock in which the sheep resided at night to protect them from local wolves. It was built to specification, she proudly declared, by a shamanic Venetian man who spent three years alone in the virgin forest of Bolivia, where he acquired much of his knowledge and wisdom. Inside the straw was fresh and dry and the circular structure had a domed ceiling crafted with all the care of a Florentine cathedral. Alina and I joked that we could have happily spent the night there instead of continuing to our air b and b.

Then came the chickens, equally spoiled in a bountiful enclosure on the hillside, made out of all organic materials.

Anna had a way with the animals. She hugged them to her chest with a filial warmth.

As we were petting the sheep, a handsome stranger wearing an embroidered scarf and long leather boots made his way through the front gate to join us.

‘Ciao, Anna!’

‘Ciao, Matthias!’

They embraced.

Matthias, it turned out, was a fellow German. A writer who had moved to Montemignaio some eight months ago where he now runs a hostel for pilgrims, Frate e Sole.

‘So, you’ve met the wonderful Anna!’ he exclaimed.

They clearly had a bond. She traded with him ‘happy chicken’ eggs, fresh vegetables from her garden and her homemade walnut liquor.

When asked about what we would be eating tonight, we replied that we hoped to pick something up at the village shop. Anna and Matthias exchanged raised eyebrows.

‘But it’s Wednesday,’ came their response. As if, of course, logically, on Wednesday the shop would be closed.

‘Sti Italiani!’ repeated Alina playfully.

We were contemplating the prospect of dining on unsalted bread and cereal bars when Matthias invited us to spend the evening together.

‘It will be a simple fare, but healthy,’ he counselled. We were in.

Matthias bid us farewell for now and Anna invited us in.

Next to a beautifully landscaped vegetable garden sat Anna’s home, an old stone building which she’d had renovated. When Covid hit in the year 2020, she had relocated from her native Germany.

It was simple but spectacular. Every room was full of ornate bespoke wooden furniture that had been made for her great grandfather – a wardrobe, desk, sideboard – all had been shipped over at great expense from Germany. Anna was in no two minds. This was now her home. And she was ‘living well’ here.

Over the next hour, Anna shared insights from 82 years of life experience as we listened eagerly to her perfect English. Though she was born in the war in 1942, she looked not a day over 60. She radiated peace around her. The secret to being happy, she advised us, is to be grateful and to live in the moment. Her home had a traditional Etruscan metal handrail and organic earthen tiles the colour of doves.

In one room there greeted us the sight of marinating eggs and vegetables, in another vegetable seeds sprouted in tiny pots and here, in the bathroom, were a range of tinctures and ointments that she had made by hand. She showed us her traditional copper Florentine bed and her office which consisted of a shelf with an old Nokia mobile phone, an address book and a paper and pen.

‘This is why I look young!’ she chortled, entreating us to follow her into the next room which contained a small library and more budding seeds.

It turned out Anna carried the seeds around with her throughout the day to make sure they were always at the optimum temperature,

‘This is my little kindergarten’ she explained with glee. ‘Right now, some are sleeping but tomorrow, who knows!’

Anna shared with us some of her prized possessions. A steel candlestick holder from the war, a signed Zingarelli Italian dictionary and a book she had made herself with thick marbled Tuscan paper containing photographs from her collection – she was an artist too, it seemed. Alongside each photo was a short description which mindfully described the scene. One showed a rag rug made out of old textiles.

The accompanying text which was tucked into a pocket, sewn into the page of the book, read:

‘After

All those clothes

Sewn, worn and torn,

After being woven into this mat,

After the passage over it

Of so many feet, big and small…

Now, finally:

Loosen the grip,

Gracefully dissolving

Into a harmony of fading colours’

Anna was dressed like a farmer in a pink jumper and dungarees and she had circled her eyes with a turquoise eye liner. It looked magnificent. It reminded me of my late Italian teacher, Andi Oakley, who would line her eyes in a glittering violet hue.

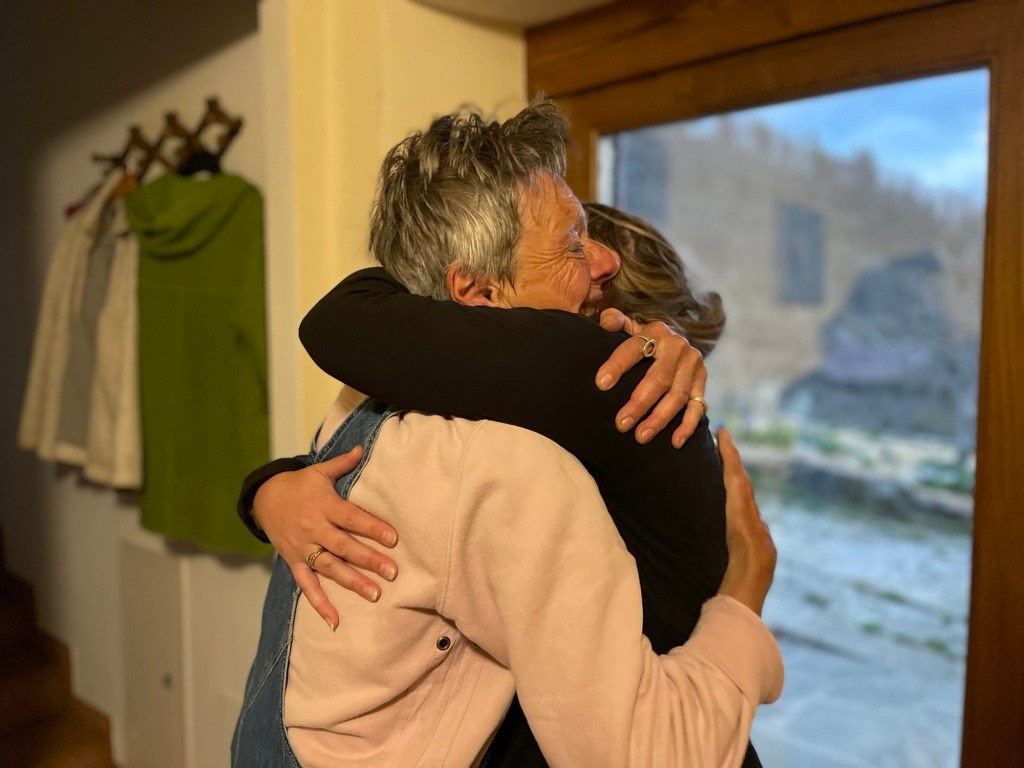

As we parted ways, Anna gave us a bottle of her homemade walnut liquor and a dozen eggs and hugged us the way I haven’t been hugged in a long time. Her arms, strong with the labour of running her little farm, held me tightly while her calloused fingers caressed my back.

Of course, we were late to dinner, but we knocked on the way down and gave Matthias the heads up.

‘We’ve been with Anna,’ we explained, and he immediately understood.

After a quick turnaround, we arrived at his homely place where he’d lit a roaring fire. We found a table set with plates and crystals that glowed in the throw of his Himalayan salt lamp. The green man watched over us.

While Anna’s walls had been bare, here art and tapestries occupied the space: Monet, Van Gogh, Kandinsky. I was quite impressed that, between us, Alina and I managed to identify nearly all of them. Next to the fire was a bible. Matthias had moved to the town after doing the St Francis’ Way, or the Via di Francesco, which runs from Florence to Rome and shares some of the same route of the Cammino di Dante, including passing through this magical town.

Matthias explained how he sought to integrate the teachings of Saint Francis into his own life: living simply, staying humble, being kind to those in need (and saving hiking strangers from starvation because the bloody shop was closed.) He made his money writing short stories for German magazines.

We ate a delicious but humble meal of homemade bread which he’d taken 24 hours to prepare using a local method he’d learnt from Anna with flour from the local mill. The salad contained fresh beetroot and the garlicy local leaf known as ‘erba orsina’, a name that refers to the fact that a bear (orso), awakening in springtime after his winter sleep, goes for this herb in order to get strong and potent again.

We discussed our mutual love of Erich Maria Remarque (Alina) and Stefan Zweig (me) and Alina read one of the poems from her new collection called, Why Do We Choose To Suffer. We discussed the meaning of leidenschaft – as artists, there is passion in a certain kind of suffering, we agreed.

This was something our feet knew all too well as we climbed back up the hill to the welcoming Agriturismo di Mela where we were greeted with milk for our morning coffee, supplies for an emergency dinner – which thankfully we didn’t need – and soft sheets.