It was a difficult day of walking starting with an overdose of gypsum followed by an unforgettable evening of hospitality and a sky full of stars.

I got up at 7am to a lovely message from my American writer friend Joyce who said she was headed to a ballet version of Frankenstein. I was jealous! Frankenstein, so misunderstood, is among my favourite books. Misread as a horror story, Mary Shelley’s novel is nothing if not a deeply romantic reflection on man’s search for connection and love.

Shelley writes,

‘If the study to which you apply yourself has a tendency to weaken your affections, and to destroy your taste for those simple pleasures in which no alloy can possibly mix, then that study is certainly unlawful, that is to say, not befitting the human mind.

If this rule were always observed; if no man allowed any pursuit whatsoever to interfere with the tranquillity of his domestic affections, Greece had not been enslaved; Caesar would have spared his country; America could have been discovered more gradually; and the empires of Mexico and Peru had not been destroyed.’

As I wrote in a recent article in The Times, I try to follow this logic with my own research as much as I can: taking my time, respecting people and not rushing to conclusions.

Indeed, part of the motive for this cammino was to take time to reflect on my research practice as a social scientist.

As I’ve been listening back to audio recordings of interviews with refugees on my way, I feel I’ve been able to hear their voices with a new attentiveness. I was taking care of myself and my own need to be outside and wonder. This would, I hoped, help me to care for other people.

For me, individuals’ wellbeing and not the political machinations of the world have always been my primary interest. One of my favourite quotes is from the French writer, Boris Vian,

‘What interests me isn’t the happiness of all people, but that of each one.’

‘Ce qui m’intéresse, ce n’est pas le bonheur de tous les hommes, c’est celui de chacun.’

I had tried to carry this spirit with me on this adventure that was also, in many ways, a self-reflective ethnographic exercise.

I headed down to breakfast where the cappuccino machine spat out my drink. The hosts were gracious and said I didn’t have to pay for the disappointing spa.

The morning was fresh but sunny. As I packed my bag, I was disappointed to learn that one of Alina’s glittery socks that I’d washed and put out to dry the night before had disappeared over the balcony. A pigeon flew into my glass door repeatedly. I closed the curtains hoping that might help.

I drank a whole bottle of fizzy water and ate a cheese sandwich for the road. Yesterday at the supermarket, I’d purchased a Red Bull energy drink which I tucked into my sack. I was still quite tired. I didn’t feel like walking today. I had even contemplated getting a taxi, but Italians don’t really do taxis and part of me had to continue. I’d see how far I got.

There was a Sardinia flag on one of the houses that lined the road, and I passed a man who was fitting new shutters on his house. A fancy-looking restaurant had hung wine bottles from an olive tree outside and the door was decorated with a sculpture made from cork.

The Dante trail takes you right through the heart of the medieval town of Brisighella. The cylindrical turret of the tower of Orologio, built for military purposes in 1290, dominates the sky above the majestic town hall.

The butcher’s shop, or macelleria, was doing a roaring morning trade and a boutique called Woman included, among the tempting items in the window, a beautiful crochet top and leather boots.

The road up out of the town was closed and so I had to take a scenic detour up some very steep steps that were about half a metre tall. I heaved myself up and the sweat was soon pouring from my forehead down into my eyes, rendering me partially blind. Leaving my bikini behind with Alina’s one remaining sock clearly hadn’t been enough to lighten the load of my heavy bag.

Succulents were nestled into the rocks and a purple flower called tassel grape hyacinth sprung out of the verge. It looked alien with its prongs – something like the covid virus. As I passed the church, the butterflies were back out in full force.

Then I was back on the path which took me into a national park. It featured an open-air geology museum on the old site of the quarry of Montecino. I was in the land of gypsum, the second hardest mineral after talc on the Moh scale of mineral hardness, or so my geologist mother had informed me. She’d kill to be here. On holiday in Tunisia she had swooned over the abundant gypsum. ‘The desert rose’, she’d called it.

The Gypsum Vein is a small mountain range characterized by one rock only, Selenite. It marks the landscape of the Apennine foothills of western Romagna. This, in turn, is made of just one mineral: shiny, soluble, slippery gypsum.

The landscape’s origin dates back to about 6 million years ago when the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean were separated and the sea water evaporation caused the formation of several strata of crystals that are the origin of today’s ravines. The solubility of gypsum produced a tessellation of caves and sinkholes (it is almost ten times more soluble than limestone), making it an area of great geological interest to Europe. The site had given rise to fossils from over five and a half million years ago: of rhinos, monkeys, hyenas, antelopes and crocodiles. But a sign made clear that fossil hunting was not permitted here. The park was to be enjoyed, not excavated.

I passed a French couple who I wished a bon chemin and stopped to locate my cap to ease the sweating situation. I had only done two kilometres but I was exhausted.

I exchanged voice notes with Alina whose mother’s house in Ukraine had been hit by a missile the day before. We shared thoughts on the mistaken assumption that refugees are somehow running away from something rather than staying to fix the problems in their countries of origin.

This brushland was a new kind of scenery for me. Something like broom scraped my arms as I walked and two mountain bikers came hurtling down the hill:

Occhio! ‘Watch out!’

‘But are you by yourself?’ one man stopped to ask me.

I was, I replied for the umpteenth time. With every time I was forced to declare it, I felt more and more alone.

I whistled back at the birds as I climbed up the dirt track road which soon turned to gravel. An orange peel left by a previous hiker was being devoured by ants.

I offloaded my empty Red Bull can in a bin in a parking lot that was next to a sign with an arrow that simply read Carne – ‘meat, this way!’

The valley had been slashed and hacked as if it had been visited by the devils in Dante’s infernal circle of schismatics.

I could hear the sound of children laughing and soon arrived at a scout camp which was surrounded by sculptures. One resembled a dragon; here was a lizard and, there, a tortured woman who made me think of the Bernini sculpture of Persephone turning into a tree to escape violation by Hades. The statue is housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

Two years ago, on a tour that I had taken with refugees, led by my brilliant friend and curator Stefania, one woman had said the sculpture reminded her of the sexual violence that her and others had experienced in Libya en route to safety in Europe. How she wished she could have turned into a tree.

The sun had gone in and it was nice and cool under the trees. In the panorama, the pine trees sprung up like bishops in a chess game.

Several scouts filed towards the camp heading in the opposite direction to me. My Granny had been a scout leader, known as Akela after the character in The Jungle Book, but I’d never been a scout myself. Though I grew up in the city, my love of the outdoors had been instilled by my mother and father through our regular walks in the ‘Country Park’, a beautiful stretch of parkland some fifteen minutes’ drive away from our house. There was also, nearby, an old quarry where occasionally, with friends, I’d swim. Once I got a fishing hook caught in my foot. That hurt alright!

My feet hurt now alright, and I was relieved to reach a stretch of downhill. But looking at the map I was reminded that what goes down must go up. Today would not be easy.

I put on some music to elevate my mood. The song, Despacito, poignantly rang out and I sang along to the Spanish lyrics. On my most recent trip to Cuba, I had teased my friend Jo by requesting the song repeatedly from the ubiquitous itinerant street musicians.

The hills undulated like pencil sharpener shavings strung out across the landscape.

The yellow broom smelt magnificent, and pinecones littered the path. The poppies opened up their petals like the wings of a butterfly. It was 1pm now and the sky was smudged with clouds. I passed a monkey orchid and bushes of juniper.

I didn’t have time to check out the Museum of Olive Oil but I was making up time on the gentle downhill patch. To look down was to see a furry black caterpillar curled in a ball; to look up was to see the vineyards dusted with buttercups.

I proceeded past a sign saying the road was broken up ahead only to find that yet another landslide had torn into the cliff face. Luckily, I was able to hop over the barrier and traverse the crevasse on the left hand side. I put on Fleetwood Mac.

The combination of smoked salmon and tzatziki was so, so good as I stopped for lunch, looking out over the vines. I noticed a worrying hole in my shoe. I still had quite a long way to go but I wanted to take a nap. This plan was thwarted by a tractor that emerged spraying pesticides.

A car sped past. But where had it come from? The road was broken? Oh well, I’d missed my chance to hitch a ride.

Some pigeons perched on an electricity wire. A delicate trace of honeysuckle decorated a laurel tree.

And now came the ascent once more. I noticed the various signs signaling that European Union money had been invested in the area and passed another landslide, though this time the road was still navigable.

My feet ached and I stopped to take some ibuprofen. Now I was listening to an audiobook that Alina had recommended, The Signature of All Things by Elizabeth Gilbert. It was about botany. I thought of my grandfather who I had never known, but who had been an academic at the University of Manchester. A doctor of blue green algae or cryptogamic botany, he had apparently been a walker too. The family legend went that he had even been shortlisted for the Edmund Hillary Everest expedition. In my dad’s house there still hung a beautiful black and white photo of him at the summit of Mont Blanc.

I tried to channel that spirit as I ploughed on with painful feet. I tried smaller steps – that hurt. I tried longer strides – that hurt too. A tiny spider hitched a lift on my thumb nail. Desperate for some company in my hour of need I played some opera music. The highs and lows of the singers’ voices matched the ups and down of the path.

My phone signal had gone so I couldn’t call anybody for motivation. The rocks weren’t massaging my feet now, they were hurting them. I’d only done 12.1 kilometres but the incline had been 72 floors.

A chapel to the Madonna spurred me on for a while, then I collapsed by some abandoned farming equipment. I would take some paracetamol too. Shit, how would I fare tomorrow, and the day after, and the day after that?

I watched a hawk sweep across the sky and contemplated it a while. It hovered then soared down in a flurry of feathers which were dark on the outer edges and a lighter brown in the middle. It screeched into the sky. I hear you, I thought. This was the sound of my foot cramps.

I put my feet up on my bag and closed my eyes. God, it felt good to be horizontal. It was nearly 4pm. In my body I felt fine. It was just that my stomach was still playing up and my feet were aching.

I carried on, listening to the sound of the hawk and dogs barking in the distance. I was rewarded by a spectacular 360 degree view of the mountains which was framed by wild rosemary and thyme and blue daisies that exited the ground in little puffs of mauve.

The pain killers had taken the edge off, but every step still hurt and I had another two kilometres to go. There was a brief flirtation of rain, just enough for me to cover my bag and myself, but then it passed as swiftly as it had arrived.

I pushed down hard on my hiking poles to relieve the pressure on my feet. By 6 o’clock, I told myself, I’d be there. I ate some pistachio nuts and carried on my way. Panting like a dog, I dodged muddy puddles here and there and noticed an interesting orange fungus on a tree stump.

A sign informed me that I was in Ca’ di Malanca where on the 10th of October 1944, Italian forces had clashed with German soldiers. There had been 42 fallen partisans. It was humbling.

The forest opened up to reveal spectacular views on either side. I saw some parasites on an oak tree and thought of Paolo back in Ravenna and his ink. What a man he had been.

Now the path led across a sheer rock face littered with boulders with precipitous drops on either side. I thought again of Dante’s hike through canto 12 of Inferno,

‘And so we made our way across that heap

of stones, which often moved beneath my feet

because my weight was somewhat strange for them.’

Attention is drawn here to Dante’s weight to stress he is a human being visiting the underworld. I hoped Dante had had good boots.

The sun was now illuminating the mountain tops in a vibrant green. Then, I could hear a dog, I saw a car and my heart started to lift. Here was Enrico, my host for the night who had promised to meet me.

I couldn’t have been more happy to see him.

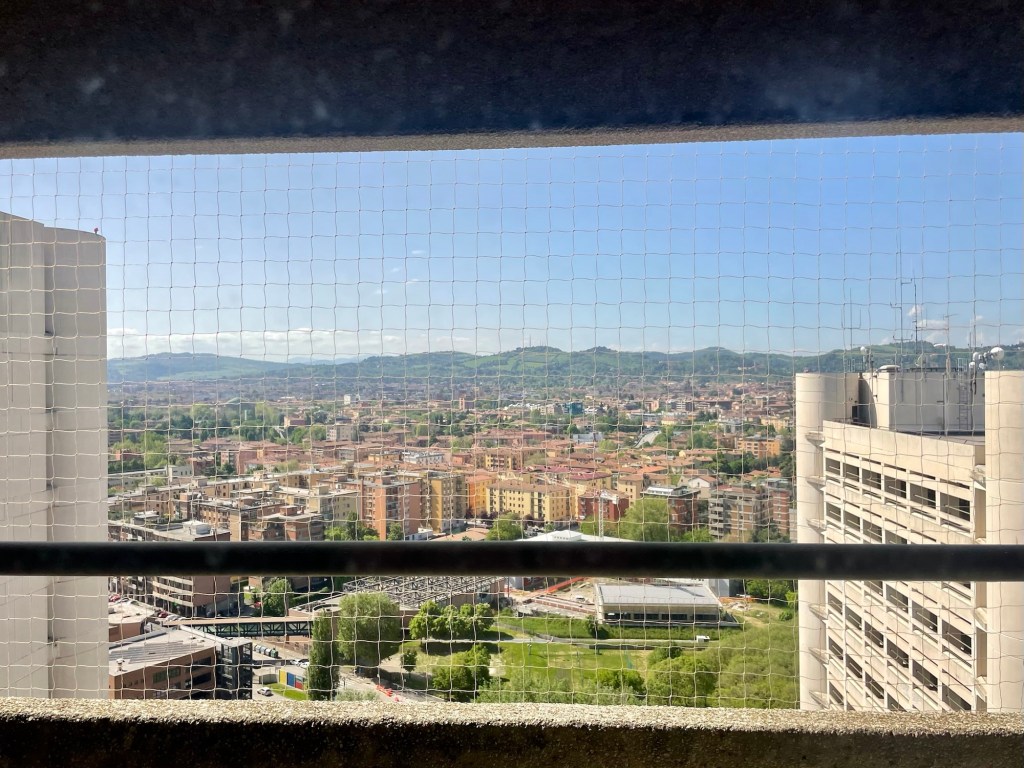

He showed me that across the ridge you could see Ravenna and, see that last line? That was the Adriatic sea. On a clear day you could see the mountains of Croatia.

I immediately liked this man who was accompanied by two adorable dogs, Mia and Cilian.

Enrico was a keen geologist and star gazer – to love planet earth is to love space after all, he explained. He was one of the patrons of the Observatory that sat atop a nearby hill. When they’d built it, they’d found an unexploded bomb from the war.

Together we passed Monte Romano, a tiny village composed of just ten houses, and arrived at his home. It was folded into the hills in the middle of nowhere. The view was breathtaking. You could see Mount Falcone which I’d crossed from Florence in the snow, and here were the origins of the Arno and Tiber rivers.

It was moving to see how far I’d come. Perhaps I could do this after all.

‘And you’re doing it without the threat of the death penalty over your head like our dear Dante,’ Enrico reminded me. We laughed.

Enrico’s wife had left to pay her respects to the late Pope at 2am that morning and so it was just me and Enrico who enjoyed an aperitivo on a little balcony as we watched the sunset. He had grilled aubergines with the local oil into a delicious sauce to make bruschetta. The olives melted in my mouth.

That night we ate tagliatelle with mushrooms he had foraged from the surrounding woodland with pepper he had brought back from Madagascar and discussed all things geology and stars beside a roaring open fire. The mushrooms were called St George’s mushrooms, since the best day to collect them was St George’s Day.

Enrico also prepared me a delicious baked potato with rosemary and some grilled cabbage and tomatoes which were served with pecorino and some local squacquerone cheese. It was all delicious.

The house was as stunning as Enrico’s cooking, with original brick walls and beams that crisscrossed above us protectively. There was an antique clock, oak furniture and a near perfect pencil depiction of Dante’s death mask which had been rendered by his grandmother’s sister for a project at school.

And then Enrico shared with me one of his prized possessions: a striking photograph of the comet Hale–Bopp which was visible from earth in April 1997. It had been one of the brightest seen for many decades.

I can still recall my mum’s excitement.

‘A comet, a real-life comet in the sky!’

I had been ten at the time. It was one of my most vivid childhood memories. It won’t return for well over 4,000 years, had marveled my mum. I wished she were here to meet Enrico.

The dogs were under the table and I tickled one of them with my weary feet. It felt luxurious. Enrico shared with me a poem he had written about comets:

Our existences flow rapidly.

Like swift wandering comets

That move

In cold, empty spaces.

Distant projects,

Guarded in the dark

Suddenly called

To the light.

Beauty and love

They light up and burn

Around this Sun.

For each, the orbit is different,

But it inexorably brings us

Back to a place that reason cannot understand.

Enrico had been the translator for Thomas Bopp, one of the astronomers who had discovered the comet before it became visible to the naked eye, on a visit to Italy during which he had signed his photograph. The photo, he proudly shared, was also featured on numerous book covers.

‘Comets now have names of computer programmes,’ he lamented, ‘not astronomers or lovers of the sky.’

This man was a true lover of the sky, just as Dante had been.

Before I went to bed, Enrico took me outside to see the stars and took my photograph beside his favourite oak tree. I felt honoured. And naturally, I recalled the last lines of the Divine Comedy in Paradiso:

‘As the geometer intently seeks

to square the circle, but he cannot reach,

through thought on thought, the principle he needs,so I searched that strange sight: I wished to see

the way in which our human effigy

suited the circle and found place in it—and my own wings were far too weak for that.

But then my mind was struck by light that flashed

and, with this light, received what it had asked.Here force failed my high fantasy; but my

desire and will were moved already—like

a wheel revolving uniformly—bythe Love that moves the sun and the other stars.’