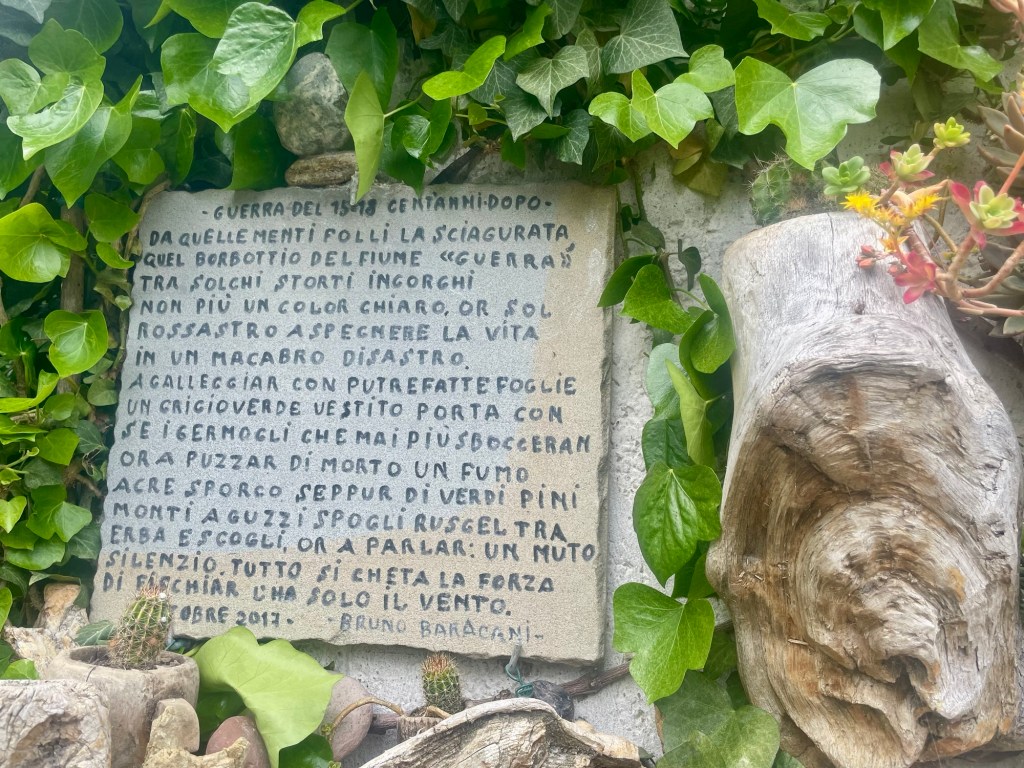

The sun shone strongly on the rolling hills and I reflected on great art’s ability to speak in indelible ink.

I woke at 7am and ate breakfast with the construction worker from Udine and a colleague of his who was also staying at the B&B, Pino del Capitano. Coffee was served in a chipped teapot.

We discussed Italian TV and the phenomenon of the velinas who are attractive women who serve at props in news and current affairs shows – showgirls, if you will. When I had started studying Italian in my teenage years, I had been struck by the sexism that dominated much of the culture, but I reflected that on my cammino I had encountered nothing but respect and chivalry.

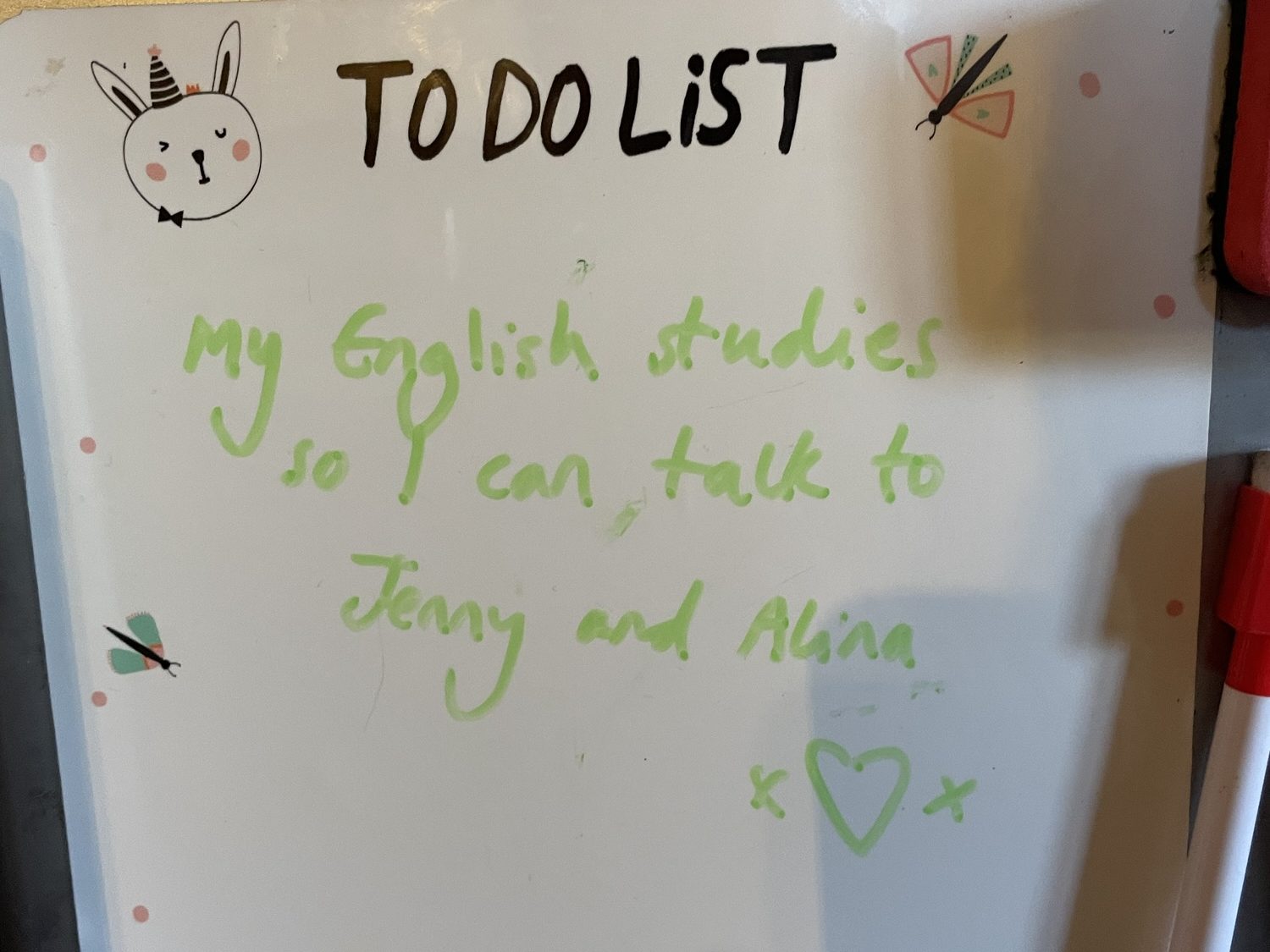

I was worried about my toes which were swollen and painful from yesterday’s fall and so I bound them together once more with some tape and plasters that had been left to me in a first aid kit by Alina. Today I would walk tentatively and see how far I got. It was going to be a case of mind over matter, for sure.

Ivan proudly showed me the lemons he had picked from his own tree. They smelt sweet and tangy at the same time. I was reminded of the citrus house in Oxford’s botanical gardens where I would sit and read as a student.

As I departed back up the valley, a line of mist like an airplane trail hung lightly in the sky. It was sunny but the air was fresh, or rather ‘frescino’.

I love Italian suffixes such as ‘ino’ and ‘etto’ which denote something as small. ‘One’ renders its subject big and ‘accio’ makes it wicked. My Italian exchange partner Maurizio had called me ‘Jennina’ – little Jenny.

I would miss speaking Italian on my return. Speaking a foreign language is like playing a musical instrument through which you get to express a different part of yourself. In French, I go by Jennifer; in Italian I am Jenny; and in Arabic I am Jen which means ‘ghost’.

Kelsey, picking up on my international mindedness and desire to incorporate all my different linguistic personalities called me ‘Jenny-Jennifer-Jen.’

As I passed down Via Garibaldi, there was a church on my left and an elderly gentleman attending to his roses. One of the gardens that lined the little path featured a tree decorated with easter egg wrappers and outside one house was an exercise bike. ‘Free to anyone who loves the planet,’ read the paper note.

As I crossed the beautiful river, I realized I was limping. The pharmacy wasn’t open for another hour so I made do with Ibroprofen and carried on my way. On the road there were shards of a car’s wing mirror that glittered in the dawn light.

I entered a café in Dicomano’s centre to grab a second coffee and got talking to three men in bright yellow nurses’ uniforms. I asked one of them about my foot. He said the same as my mum had, to lance my toes together, put my foot up with ice and rest. I told him that this wasn’t a possibility and that I had to continue.

‘I see,’ he responded with a smile. ‘So, you grind your teeth and carry on, girl!’

The gaggle of men sitting smoking outside could have been intimidating, but I wasn’t self-conscious at all. On the contrary, I felt welcome. There was a self-service laundromat and a shop called Meat Matters, both of which were yet to open.

I walked alongside the river for around 20 minutes. Some graffiti said, ‘all cops are bastards.’ There was a beautiful little allotment on the left and an avenue of cypress trees to the right. I crossed beneath a short railway bridge which even touched my head at five foot two.

A man was walking a ridiculously small dog in a gilet.

I read a sign alerting me that I was on the Path of the Powerful Arno, also known as the ‘Path of Partisans’. In the Spring of 1944, the resistance to the Nazis had grouped together near here and walked to Florence which they would finally liberate on August 11th. I thought of one of my favourite Italian writers, Elsa Morante and her novel La Storia, which means both story and history. It narrates the life of a single mother living under Nazi occupied Rome:

‘Freedoms are not given,’ she writes, ‘They are taken.’

It was hot and I was sweating as I left the river and mounted the rise out of the town. A school bus went up the hill and down again. I’d really come to appreciate nicely ploughed agricultural land; the brown earth was spilling up its guts, vulnerably awaiting new crops. Someone had a boxing bag hanging in their garden.

Today I felt like walking in silence. I was nearing the end of the cammino and every second was important. Every now and again a stone would get caught just under the front pad of my left foot, sending a shooting pain up my leg. But I was on the way of the partisan. What did I have to worry about, really? It hurt, but I could still walk and walk I did. My right calf twinged. Perhaps I was overcompensating for my left foot?

After yesterday’s multiple diversions, I kept religiously checking that I was on the right path. I saluted the town as a train chugged by, turning the corner into a silver cobweb that broke upon impact with my nose.

A flurry of flowers, a kind of sage I think, were covered in ‘cuckoo spit’. The phenomena actually has nothing to do with cuckoos or spit at all. The foamy liquid is caused by a type of bug called a froghopper nymph, also known as a spittlebug. The insect feeds on sap found in plant stems and leaves behind blobs of this spit-like goo.

I saw a new type of butterfly – yellow and black in the middle, its wings became translucent at the ends.

There were white flowers with yellow middles, pregnant with pollen and I was happy to see the bees enjoying it. The shadow from the trees was merciful as I made my way up a steep uphill path. The sedimentary rock crumbled in clumps beneath my feet.

I followed the navigator on my phone down a little path where the grass was really tall, stopping to pet two golden retrievers who accompanied me for a short while. One licked my hand which was salty from the sweat.

A stack of abandoned beehives looked like filing cabinets on the hill.

Though the sun was maturing in the sky, I resisted wearing sunglasses as I wanted to enjoy every bit of the view. I wished I hadn’t left my sunscreen behind and trusted that my cap would offer sufficient protection.

A man was sat reading in a field of chickens. A tabby cat crossed the path in front of me, reminding me of my own cat, Dante, back home.

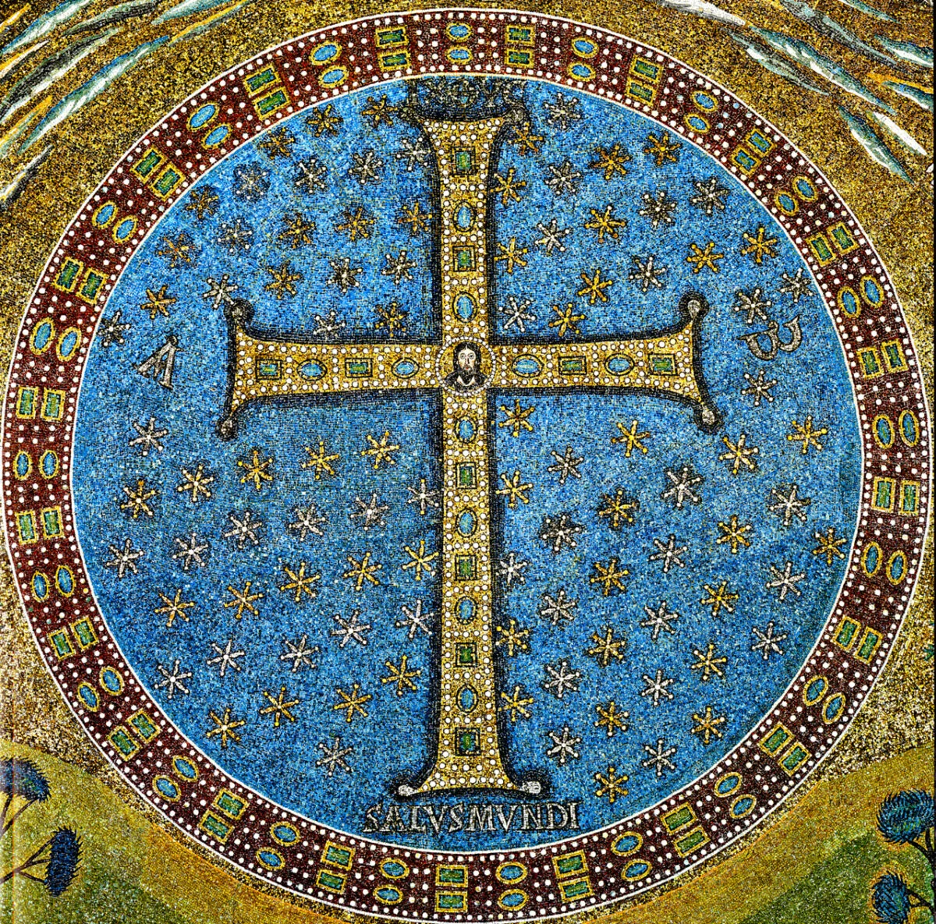

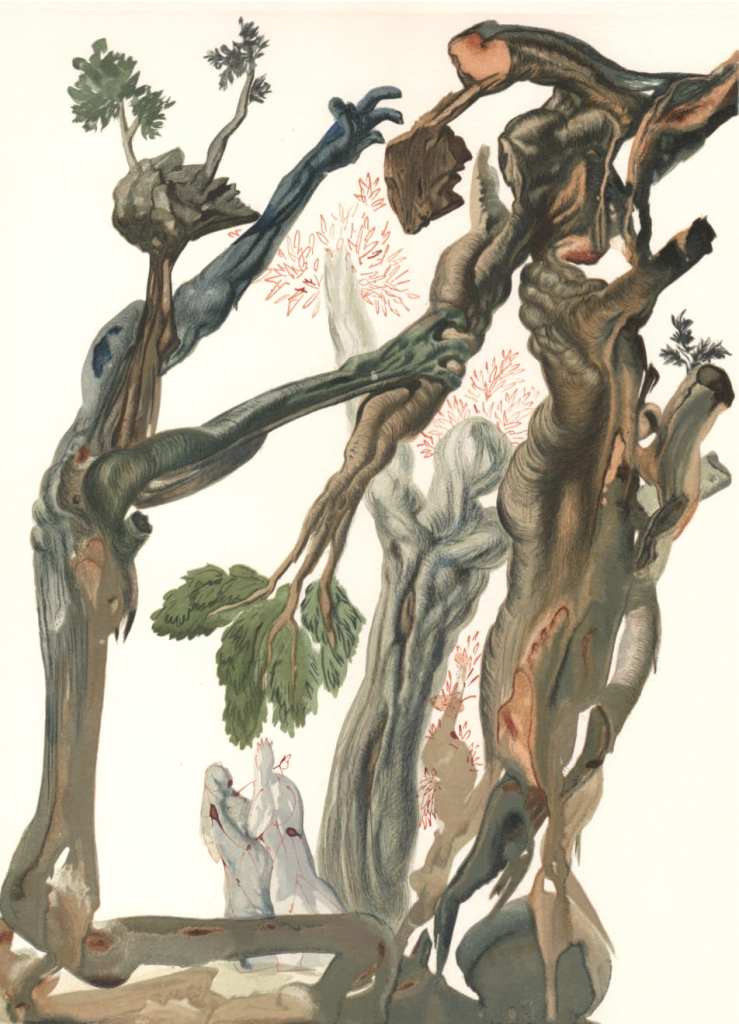

As I passed a vineyard, I realized something momentous. The vines which I had identified at the start of my walk as tortured souls from Dante’s wood of suicides now appeared to me as yogis mindfully stretching their limbs towards the sun.

My depression had lifted and I felt quite transformed in body and spirit.

All the nettles of the region seemed to have assembled here from where they stung me through my leggings as I crossed the overgrown field. My boots were snagging on sticky weed and there was a landslide. Then the overgrown foliage transformed into a perfect lawn.

I stepped in something only to release that it was the entrails of a dead deer. The back half of its carcass was a little further up the path. Flies were making a feast of it. What could have got it, a wolf?

As I passed a series of small waterfalls, I noted the ferns that sprung up in fans like toilet brushes. The landscape felt almost tropical. A pock marked cliff face protruded onto the road.

I crossed a rickety wooden bridge and a sign that led to the Poet Hotel. What I assumed to be a father and son were playing in the stream.

Three hours had passed since I had left and so I stopped to take some more pain killers, observing a plastic unicorn rocker and succulents on the wall.

Accompanied by the sound of the stream I felt like listening to Neil Young’s Harvest, one of the few CDs I had bought with me aged 18 as I trekked through India and Nepal.

‘Will I see you give more than I can take?

Will I only harvest some?

As the days fly past will we lose our grasp

Or fuse it in the sun?’

Silverlake Ranch emerged and I greeted 12 horses who were each stationed in their own field by a reservoir.

The church bell sounded out at 11.58am, two minutes early. A spider had caught a fly in its web and it was slowly disintegrating. And there sat the spider proudly on the top of the grass.

I was about half-way to Pontassieve and my broken toes were feeling it. I would stop in the next village and assess the situation.

I arrived in Galardo to the smell of woodsmoke and strings of drying laundry that lined the narrow streets. Someone had decorated the front of their house with purple and orange snapdragons. I took one between my fingers and made the familiar mouth shape: snap! Some mushrooms were colonising a tree.

I stopped at a bar overlooking the river and ordered a coke zero and tuna and tomato stracciata. The type of bread – salty and delicious – suggested I was getting near to Florence. I knew better this time than to ask for cheese, and it tasted all the better for it.

The owner, Sofian, was from Tunisia and so we exchanged a few words in Arabic. He had turquoise eyes that were quite captivating.

‘We get a lot of pilgrims who stop here on the cammino di Dante but also the Via Francesco. But you’re the only person I’ve met who has gone it alone. It must be tough, especially for a woman.’

‘Not really,’ I replied.

I explained to him about my broken toes and he suggested I take a lift to Pontassieve with a local guy who would be passing by shortly to pick up some wine. The wine was made in house. Next to the bar there stood a heavy metal corking machine.

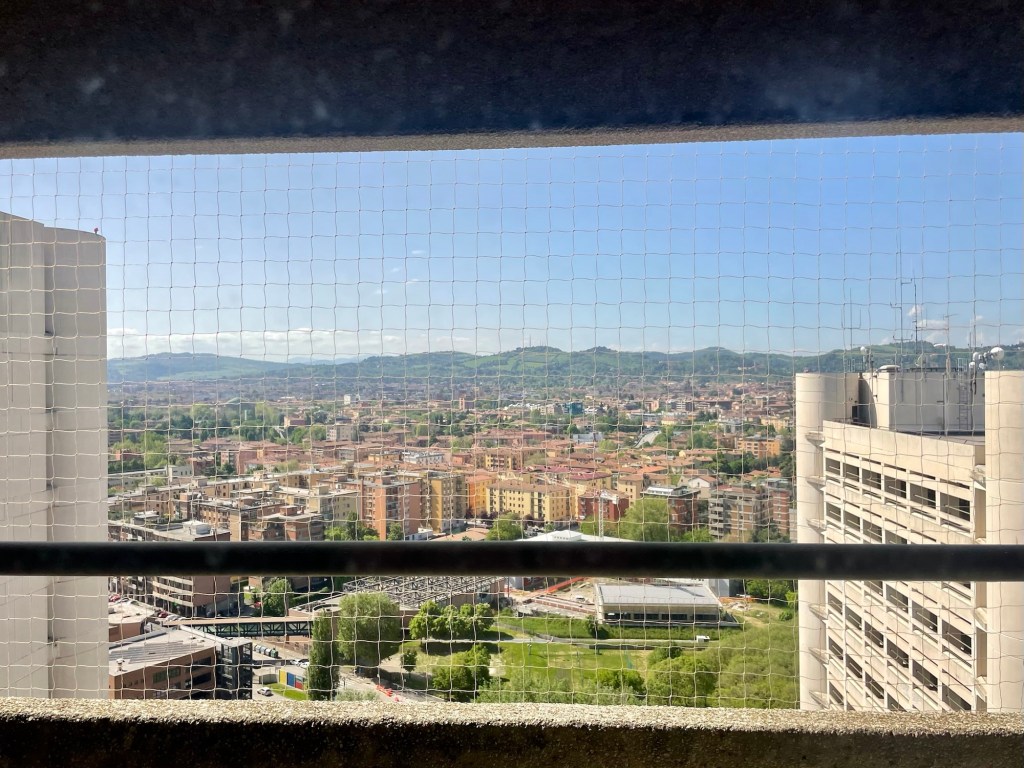

It was tempting. I was determined to walk the full way back to Florence tomorrow and I’d already done 15km today and climbed 75 floors. I could wash my clothes, catch up on my blog and be ready for tomorrow which would undoubtedly be a day full of emotion. Kelsey and Alina were going to meet me in Florence along with Professor Alberto Tonnini from the University where I’d taken up a visiting professorship in 2023.

Otherwise, there was the train or the bus, counselled Sofian. I heard him on the phone explaining that there was a ‘pretty blonde girl who wanted a lift’.

Within ten minutes, Maurizio had arrived. He was a gentle older man with a solid grey moustache who drove a green jeep.

‘Sorry for the mess,’ he offered. ‘For me a car is a way to get from A to B and nothing more.’

I offered him a drink and, with speed he downed a glass of rose.

I thought of Virgil seeking out a shortcut from him and Dante in canto 11 of Purgatorio,

‘to reach the stairs; if there is more than one

passage, then show us that which is less steep;for he who comes with me, because he wears

the weight of Adam’s flesh as dress, despite

his ready will, is slow in his ascent.’

See, even Dante had taken it easy sometimes.

In the car, Radio Capital, a Roman station, played out a solid mix of 90’s tunes. Maurizio explained to me that he was retired but still repaired cars with his son for a living. But today was May 1st, workers day, and so he was having a day off.

As we passed the medieval bridge, he explained that a ‘bomb of water’, or flood, had hit the town on March 15th, causing damage to its foundations and inundating the football field. There were logs that had been carried by the surge still deserted on the banks of the river.

‘Luckily no one here was hurt,’ Maurizio sighed. ‘You hear the sound of water and you can’t do anything.’

I thought back to Rossella and her animals, not all of whom had survived the floods of 2023.

Maurizio left me by the town hall in the old city and wished me well,

‘Be careful in Florence,’ he advised me, ‘the political rivalry of Dante’s day continues there today.’

‘Oh, there’s the local major,’ he said, waving, and then he sped on.

I felt vindicated in my decision to dye my hair blonde which had clearly played a role in me getting a lift.

I strolled around the old city walls and was surprised at the decent size of the town. There was a United Colours of Benetton and a shop that sold nothing but sewing machines. A man’s barbershop was full of beautiful antique equipment. I saw my reflection in the window – the top of my shoulders were red with sunburn.

I climbed up a little side street that smelled of soap and up a very steep hill to the apartment where I would be staying that night, La Taverna di Caterina. There were orange trees on the terrace and a sweeping view of the city.

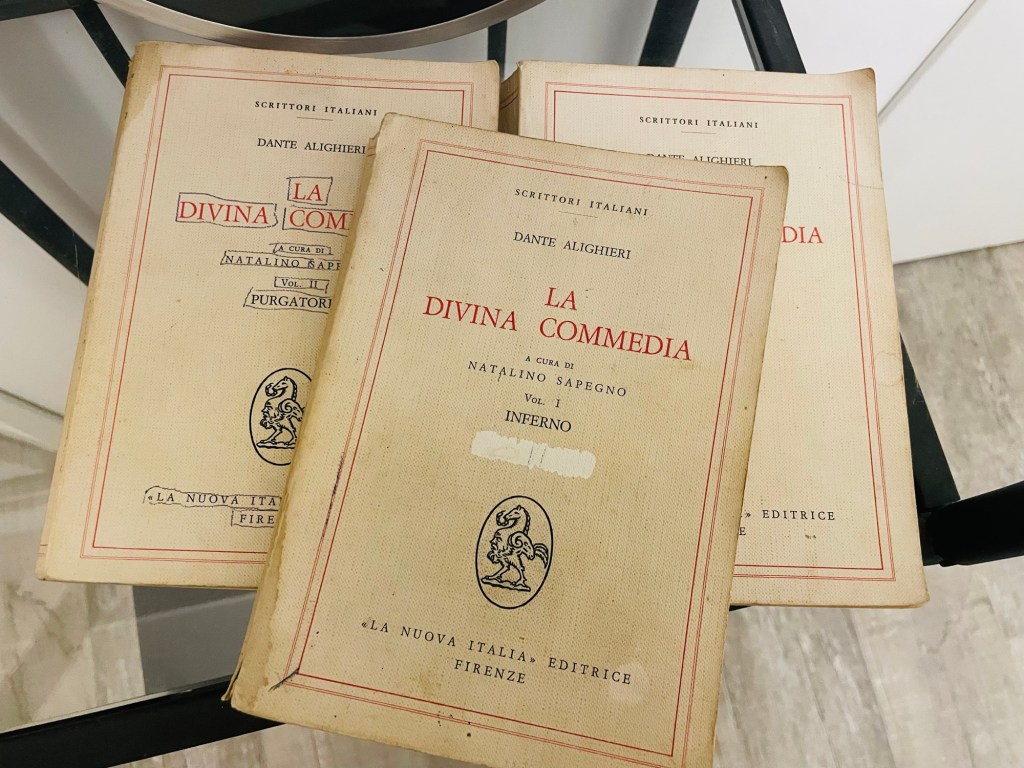

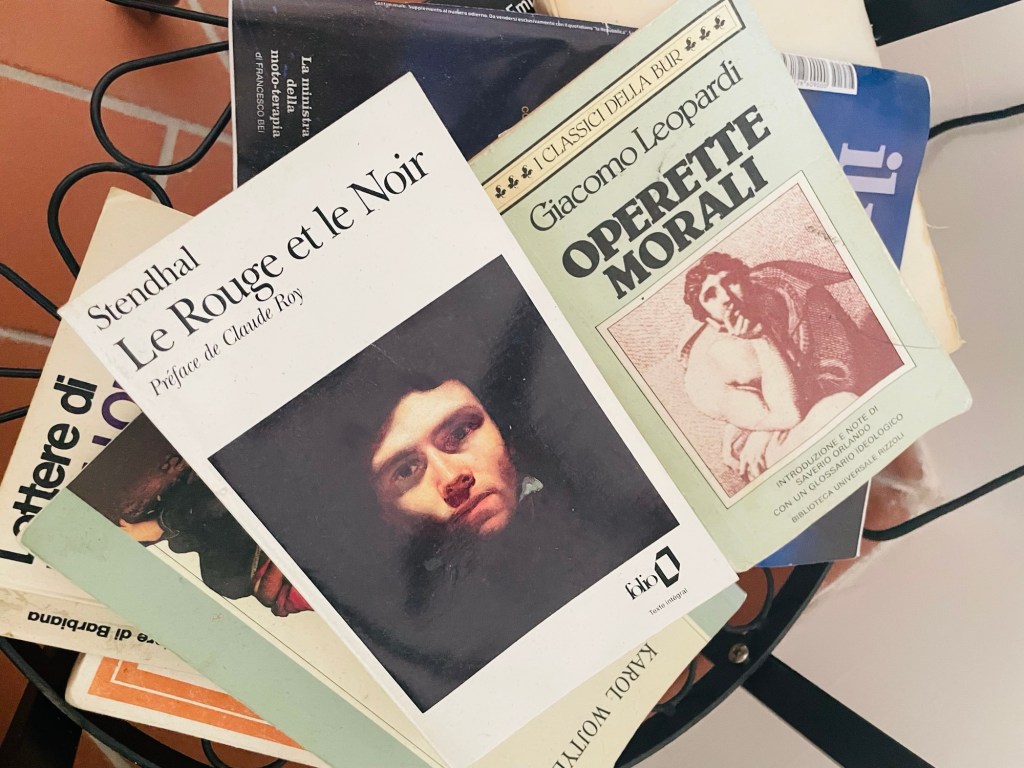

Caterina’s daughter Anna showed me the lovely flat which had a round table outside for writing. Inside there was an amazing selection of books including The Red and the Black by Stendhal and verses by Leopardi.

I thought back to Stendhal’s romantic novel.

‘A good book is an event in my life,’ he had written.

As I washed my face in the sink, I realized I had come out in spots from the constant sweating. There was a heatwave back in England my mum messaged me to say and I wondered if she had caught the sun too.

I did some writing, caught up on work emails and then wondered back into the town.

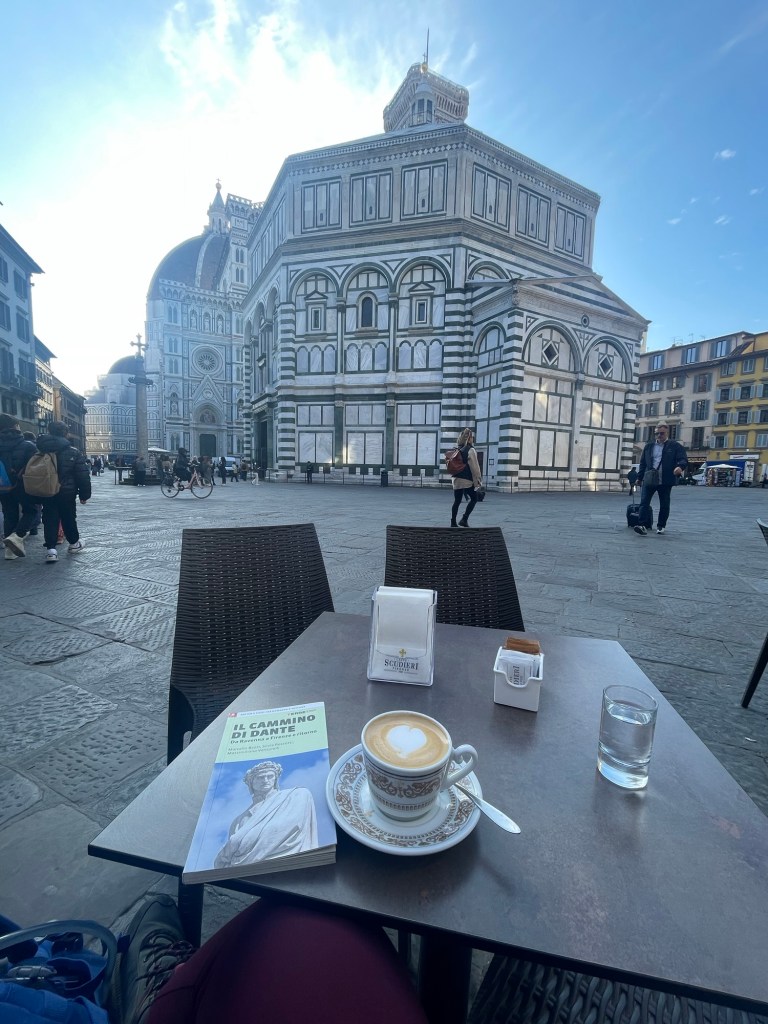

Since the start of my cammino, I had wanted to do something permanent to mark the adventure and my relationship with Dante, so as I passed a tattoo studio I tentatively walked in and inquired if they had any spaces.

They did.

I spoke with Massimiliano, the lead tattoo artist and explained something of my journey and intention. Then, as if by magic, out he whipped a copy of the Divine Comedy from his backpack.

‘I always carry it with me,’ he said, ‘here and there I read a verse or two.’

It felt meant to be.

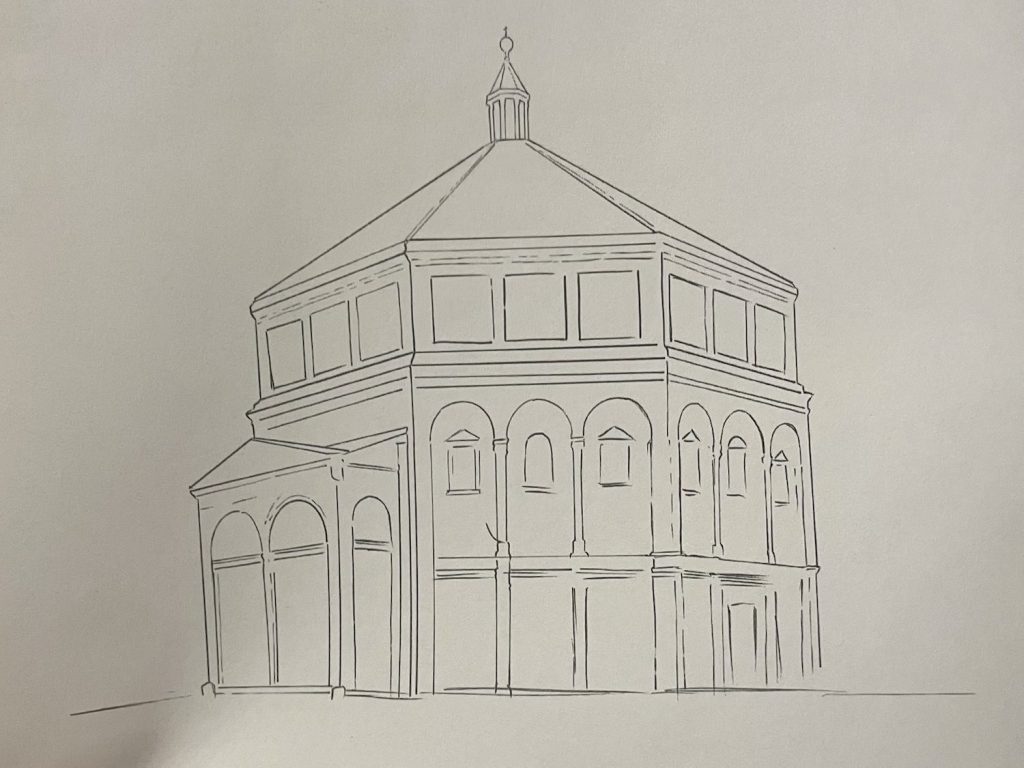

Together on an iPad we designed a simple outline of the baptistry where Dante had been baptized and where he had wished to return a poet and assume the laurel crown. It was more original that getting a tattoo of the Duomo which was very popular in these parts, Massimiliano said. His dad was from Florence. This was the first time he’d tattooed an English person.

Two other female tattooists, Asia and Claudia, were working and they were chatty and curious to hear about my walk and my blog.

Massimiliano had to go and collect his daughter and so I sat with Claudia who realized my tattoo. She inked the small design in a subtle terracotta colour that I associated with Florence.

‘You’re not thinking of your feet anymore,’ she said, as the needle buzzed across my arm.

And then it was finished.

‘Now you’re more Florentine than me!’ Claudia announced.

I was thrilled with the finished product and celebrated by going to a sushi bar where I necked a platter of dragon rolls.

Underneath my jacket I stroked my new tattoo. It was a work of art, a testament to what Dante calls ‘visibile parlare’ or visible speech. A picture could say a thousand words.

‘I see you,’ this tattoo seemed to say.

‘I see the pain of exiles and I am committed to documenting it.’

‘I have walked 400 kilometres and more to re-see the beauty of Florence and there, tomorrow, may I find peace.’