Renaissance paintings line the route, but be wary of getting lost in the wood of suicides.

Though I remain determined it is what Dante would have wanted, starting my pilgrimage in Florence, Dante’s birthplace, rather than his site of exile and death, Ravenna, had the drawback of beginning with what is said to be the hardest day of the cammino: 30 kilometres with an ascent of 895 metres. Though I’ve been training back in the UK in the Peak District near my home, I was somewhat daunted as to how the day would unfold.

I woke around 7am to the sound of birds singing and the chiming bells of Santa Spirito, the ‘church across the river’. I left Anna and her family sleeping soundly as I packed up my bag and tried discretely to exit the jewelry studio through the glass double doors that opened onto the quiet street. Succulents a hue of pink and green occupied window boxes along the cobbled passage into which the sun was sneakily smuggling its first rays of the morning.

In Santo Spirito square the market sellers were already setting up their stalls: leggings, knickers, pot plants, copper bracelets and beaded earrings the size of oranges. Two dogs – one caramel and fluffy, one white and slick – frolicked by the central fountain while their owners puffed on cigarettes and made casual conversation.

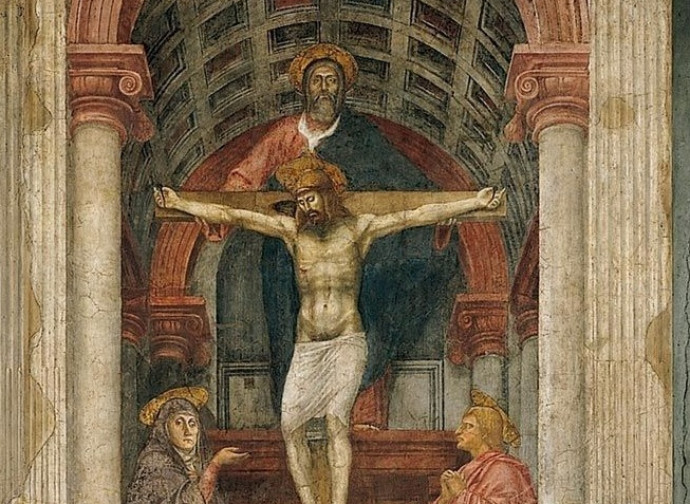

I took an espresso macchiato and looked across at the church. Among other delights, it contains the Madonna with St. Catherine of Alexandria and St. Martin of Tours by Filippino Lippi. The altarpiece is also known as Pala de’ Nerli from the name of the commissioners, Tanai de’ Nerli and his wife Nanna, who are shown in donor portraits at the sides – the Renaissance equivalent of a selfie.

The painting was commissioned by the church in 1494, so some 100 years after Dante walked the squares of Florence. Lippi’s style is sensual. Gone are the 2D Giotto era portraits of Jesus looking like an adult squeezed into a baby-sized body. Lippi was a contemporary of Botticelli whose fleshy Madonnas continue to mesmerize visitors to the Uffizi with their delicate features.

The Uffizi Gallery literally means ‘offices’. It is named after the seat where the city’s rulers used to conduct their affairs. Once business was conducted in the Bargello, now an art gallery home to dozens of Donatello sculptures where Dante would have served as a member of the political elite.

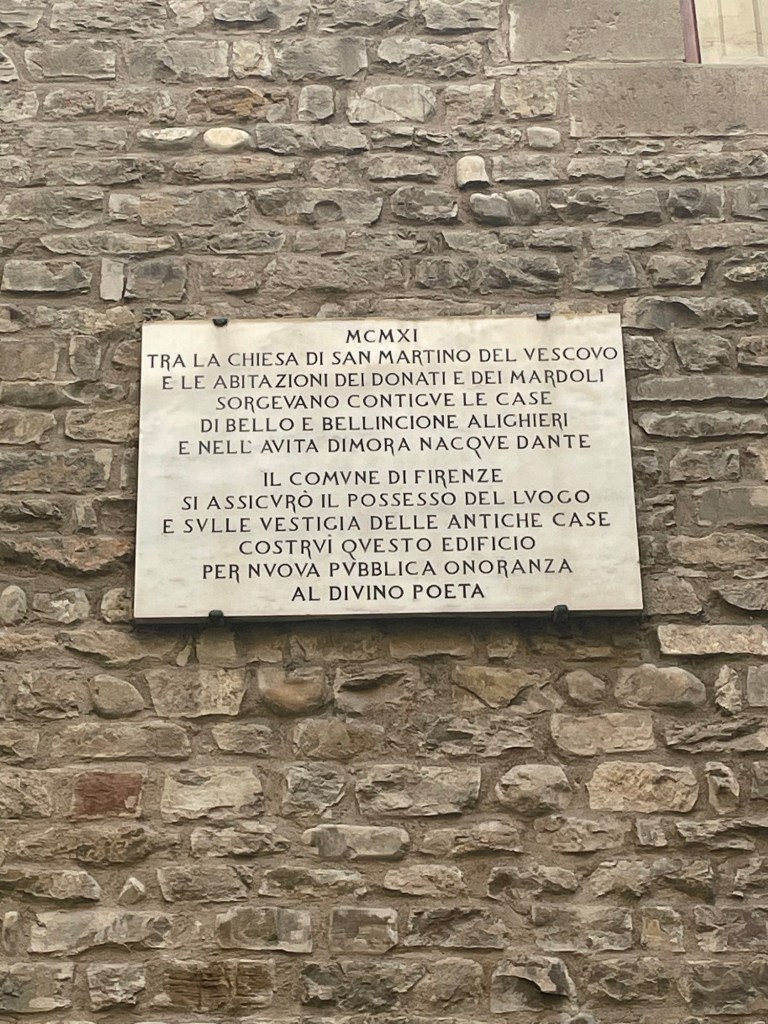

The Bargello is the ideal venue to trace the complex relationship between Dante and his home city. In the Sala dell’Udienza of the then Palazzo del Podestà (today the Salone di Donatello), on 10 March 1302, the poet-politician was condemned to exile. In the adjacent Cappella del Podestà, a few years later, Giotto and his school portrayed Dante’s face for the first time, including him in a fresco among the ranks of the elect in Paradise. It is said to be the first ever portrait of Dante.

The façade of the Santo Spirito Church is striking in its simplicity. As I passed and continued towards the Ponte Vecchio, runners wove in and out of my path and trucks disembarked cargo to one of Florence’s hundreds of eateries. One box read, ‘Lobsters and fresh mussels.’

An Asian couple were taking wedding photos on the famous bridge which connects the Uffizi Galleries to the Pitti Palace which the Medici once called their home. Her veil glittered in the morning sunlight as the photographer insisted they ‘kiss, kiss, kiss!’

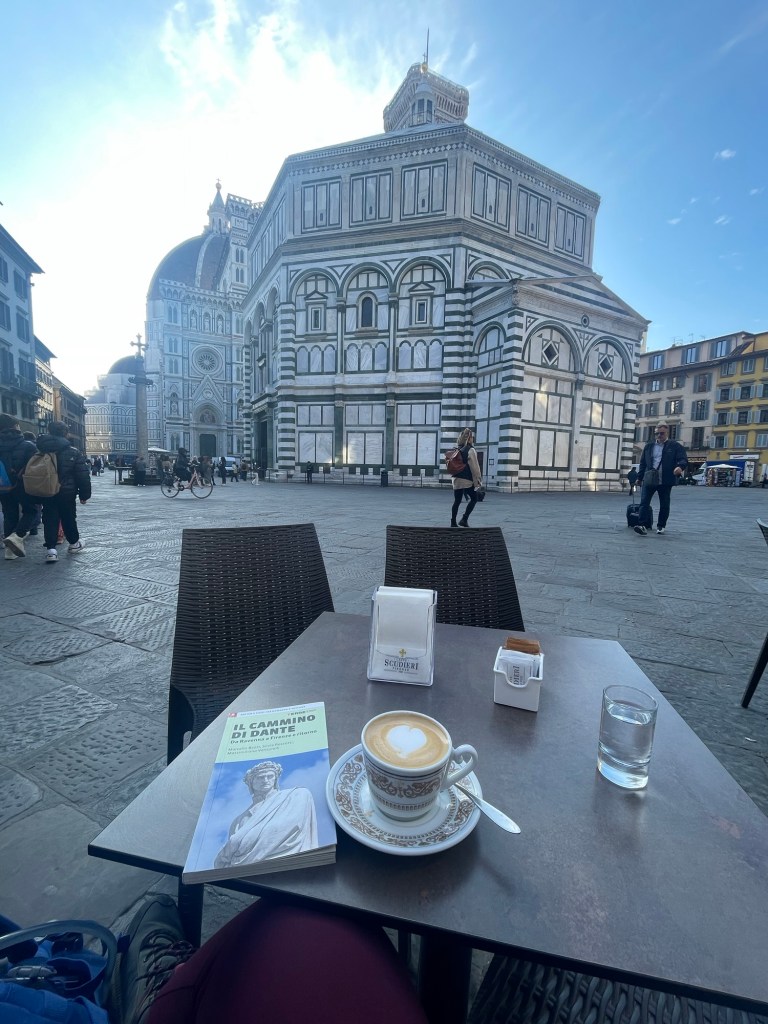

I took a second coffee when I reached the Piazza del Duomo which, unlike the rest of the still sleepy city was bustling with life. Tour groups followed umbrellas like leaf cutter ants and carriages pulled by horses escorted tourists through the narrow streets. In Venice, the streets are known colloquially as ‘rughette’ or ‘little wrinkles’. I smiled as I recalled this fact, spreading wrinkles across my own face.

Then came the time for our meeting.

Alina arrived, her flaming red hair licking her collarbone and cascading over her shoulders.

She was wearing a beautiful black coat over sweatpants and a running jacket designed by one of the fashion houses for whom she had previously laboured. She had succeeded in stashing a huge amount into her small backpack.

‘That’s what comes with moving around a lot,’ she said. ‘And the coat? Well, if you invite a refugee on a walk, they likely only have one coat, and this is it.’

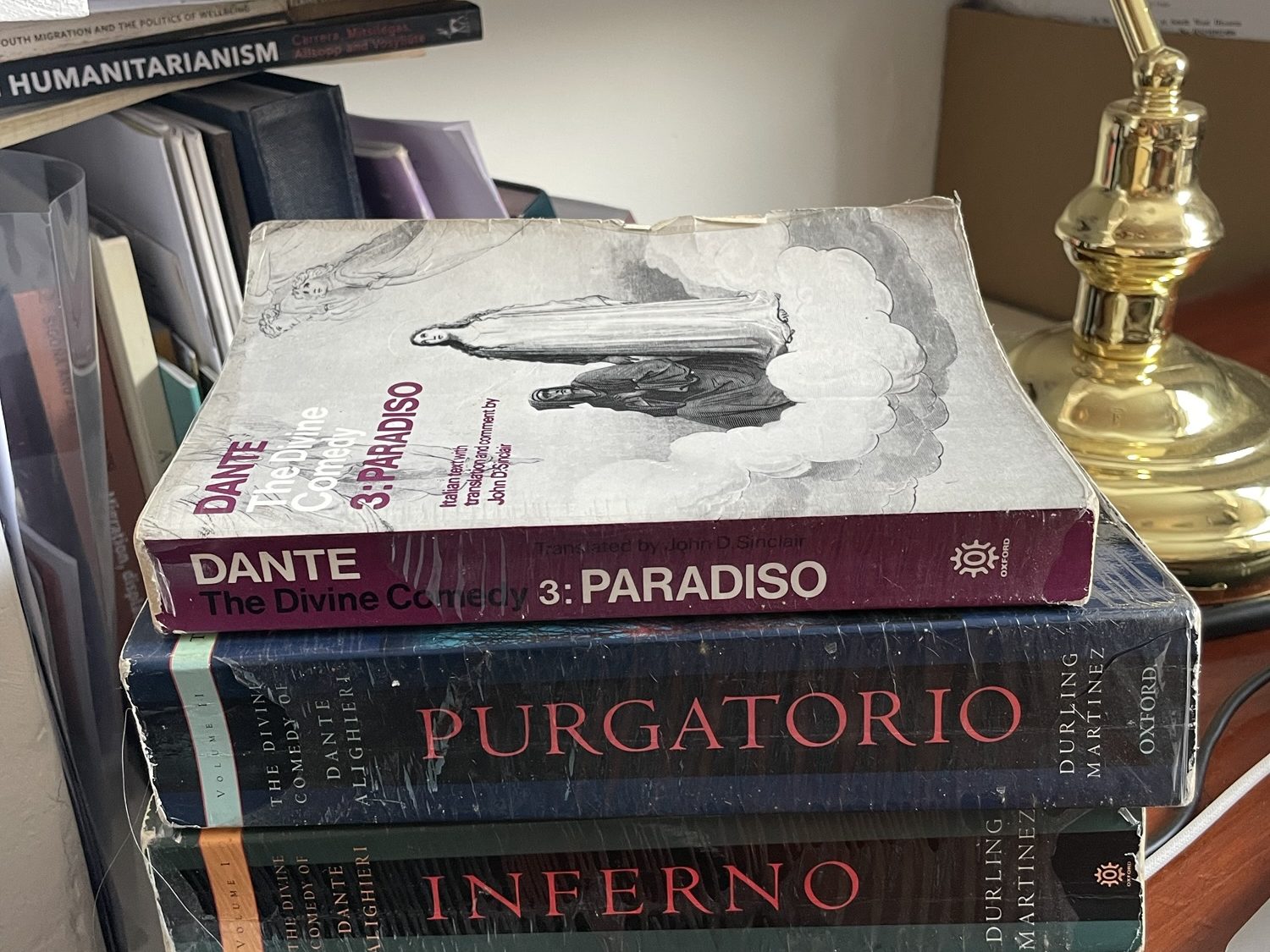

We hugged tightly, shedding the first of what would be several tears over the coming days, and reached out and touched the walls of the baptistry where Dante had been immersed in 1265 and to where he had hoped one day to return as a poet post-exile. In Paradiso canto 25 he writes,

‘If it should happen . . . If this sacred poem—

this work so shared by heaven and by earth

that it has made me lean through these long years—

can ever overcome the cruelty

that bars me from the fair fold where I slept,

a lamb opposed to wolves that war on it,

by then with other voice, with other fleece,

I shall return as poet and put on,

at my baptismal font, the laurel crown .’

‘Se mai continga che ’l poema sacro

al quale ha posto mano e cielo e terra,

sì che m’ha fatto per molti anni macro,

vinca la crudeltà che fuor mi serra

del bello ovile ov’io dormi’ agnello,

nimico ai lupi che li danno guerra;

con altra voce omai, con altro vello

ritornerò poeta, e in sul fonte

del mio battesmo prenderò ’l cappello . ‘

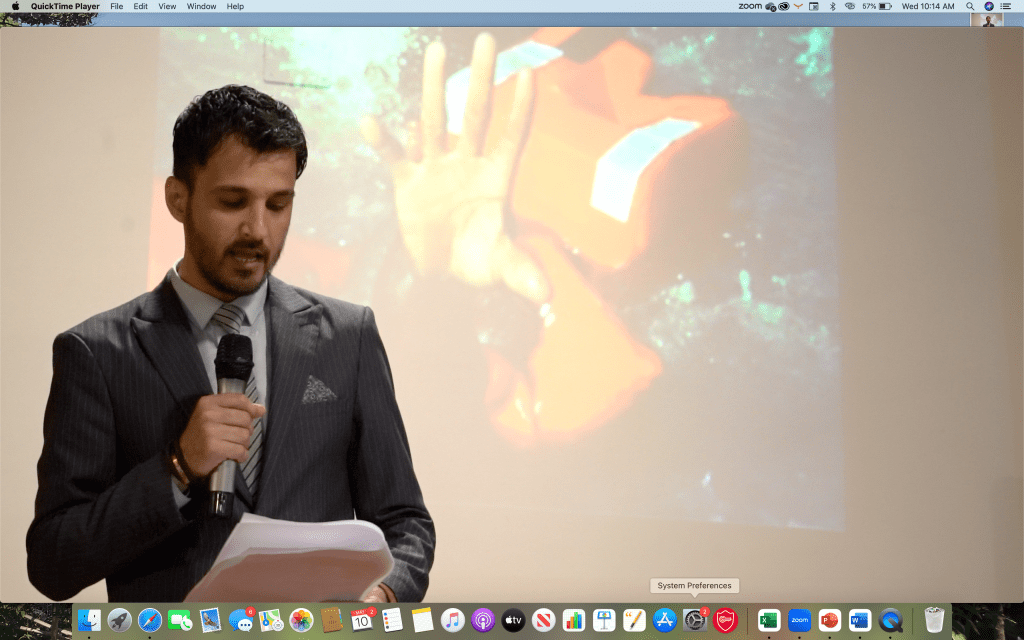

It is tradition to depict poets in Italy with laurel crowns, one now adopted by students who port the symbol on graduation day. When we completed our Reading Dante with Refugees course in Rome, I made sure that all of the students received from Stephan, the Director of the Trinity College Rome Campus that hosted us, a laurel crown.

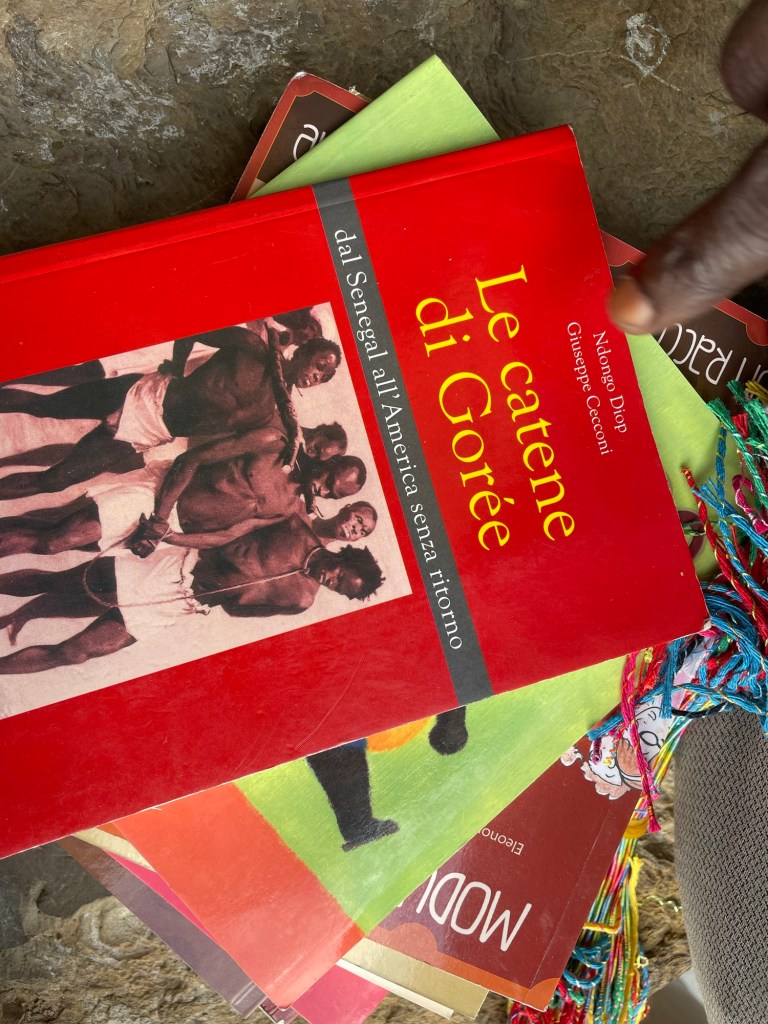

Alina, a Ukrainian refugee fashion designer turned feminist activist, was one of the eleven refugee students who took my class. For her final project she imagined her own journey from Inferno to Paradiso through the lens of the Italian bureaucracy. In the short film she made for the course, Paradise of Exiles, she shows herself moving from the dark wood (she literally, set off at 2am to shoot in woods outside of Rome) followed by the Purgatory of refugee status determination and the eventual Paradise of finding peace in Rome’s art scene. She filmed the final scenes at an exclusive shoot at the Galleria Borghese where my friend Stefania Vannini is a curator. She looks resplendent with her red hair against the green walls. I’m there in the background cheering her on.

Since the course finished two years ago, I have become somewhat of a mentor to Alina, even though she is only five years younger than me. I know the value of mentorship having experienced it first-hand myself so many times over: Julie, Andi, Janey, Joyce – you know who you are.

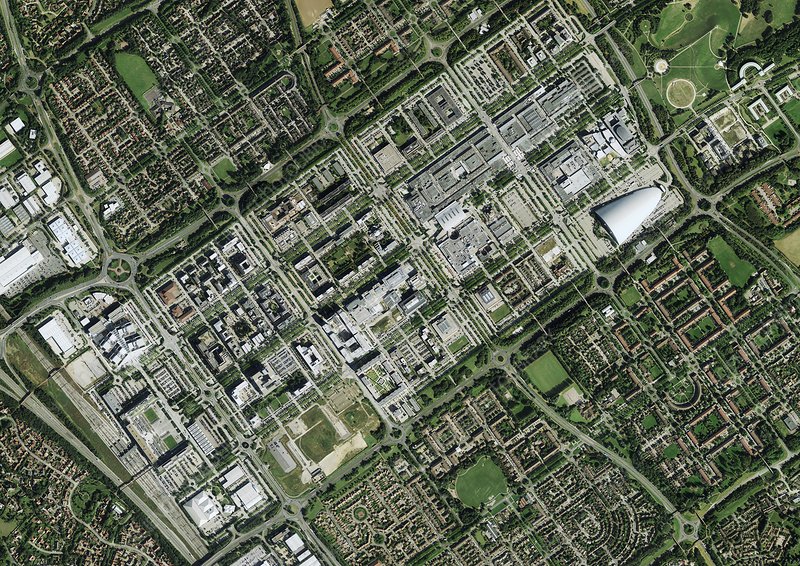

We took our time winding through the bustling morning streets before passing to the river, beside which we hiked a good few kilometres before turning up a road that led us outside of the city. For the entire morning, the Florentine landscape peaked out behind us like a jester egging us on. Each time we turned around she was more distant. I thought of Dante and how close he would have come in his exile. While we know, as this trek honours, that he dwelled at several lodgings by the river Arno, did he get close enough to see the cityscape which then would have been teaming with medieval towers and devoid of today’s famous domed landscape curated by Brunelleschi and Giotto?

Swallows sprung from under bridges and inside cemeteries, disturbing the air with the gentle flap of wings. Street corners were embellished with Madonna and child.

Alina and I chatted fluently in our colloquial mix of Italian-English as we followed the path up, up, up and left the gilded city in our trail. At 11.30 on the dot we stopped at a bench overlooking the city for her to join a call with two interns working for her holistic creative agency, Sensi, who were running an event on refugee wellbeing. I took the time to check our route and enjoy the delicate scent of crocuses that filled the spring air.

Despite her small bag, Alina had packed in an impressive amount of food including ‘unsalted bread’ from her local Bangladeshi deli. I was relieved to find that I was able to stomach dates again after a traumatic incident in Syria where I spent a 12-hour bus journey to Jordan munching on a bag-full only to find, upon sunrise, that it was also filled with ants. Oh well, protein is protein.

Alina shared her news and I caught her up with my life. We’d both spent depressive winters hiding beneath the sheets of our beds and were grateful, like the crocuses, to be coming back to life. I had nominated Alina to be part of the Nobel Women’s Initiative Sister to Sister mentorship programme in 2023 and now she’d been invited to participate in a peacekeeping mission to Ukraine. It’s a funny kind of pride I felt as both a teacher and a friend.

‘It’s about time women got some coverage in the Ukrainian-Russian conflict in Britain,’ I commented. ‘Too true,’ she observed.

Once we had taken in the last glimpse of the Duomo it was after lunch. We ate schiacchiata sandwiches, a Florentine delicacy which literally means ‘squashed together’.

The day was hot.

In the town of Bombone we stopped to refill our water bottles and I marveled at the fact that the town council had voted to put in a well that featured not just purified still, but fizzy water. I made the mistake of filling my camel drinking pouch with it, only for it later to explode inside my bag. Luckily though my bum got soaked, my laptop survived.

We met a kind faced 80-year-old lady who Alina showed how to use the fountain,

‘In all these years, I’ve never known,’ she said. ‘Buon cammino!’

A lot of Alina’s utterances start with the phrase ‘before the war’, just as mine do with ‘before my divorce’. Before long we were completing each other’s sentences.

‘Before the war, I got my eyebrows done.’

‘Before the war, I worked for Alexander McQueen.’

‘Before my divorce, I worked for openDemocracy’

‘Before my divorce, I thought that by simply loving people I could change the world.’

Perhaps something of the latter is still true.

Mum dropped me a text asking how it was going, addressing me as ‘her Marco Polo’.

‘Benissimo,’ I replied.

I was so happy to see Alina.

Despite her slender Ashtanga yoga and capoeira molded frame and my own body, bloated with anti-depressants, she was less trained for the hike than I was. She pushed on honorably in her sneakers rarely complaining or even stopping to drink water. Layers were taken off and on as we moved in and out of the sun.

‘I can’t get over the fact someone has gone to all this effort to mark this trail!’ I kept repeating, euphoric that someone out there might be more obsessed by Dante than me. Each sign post for the Dante trail had been marked with a red sticker on a lamppost or a wooden sign with the letters CD singed into it by hand by the trail’s father, Oliviero Resta, who I hope to meet in person in Ravenna.

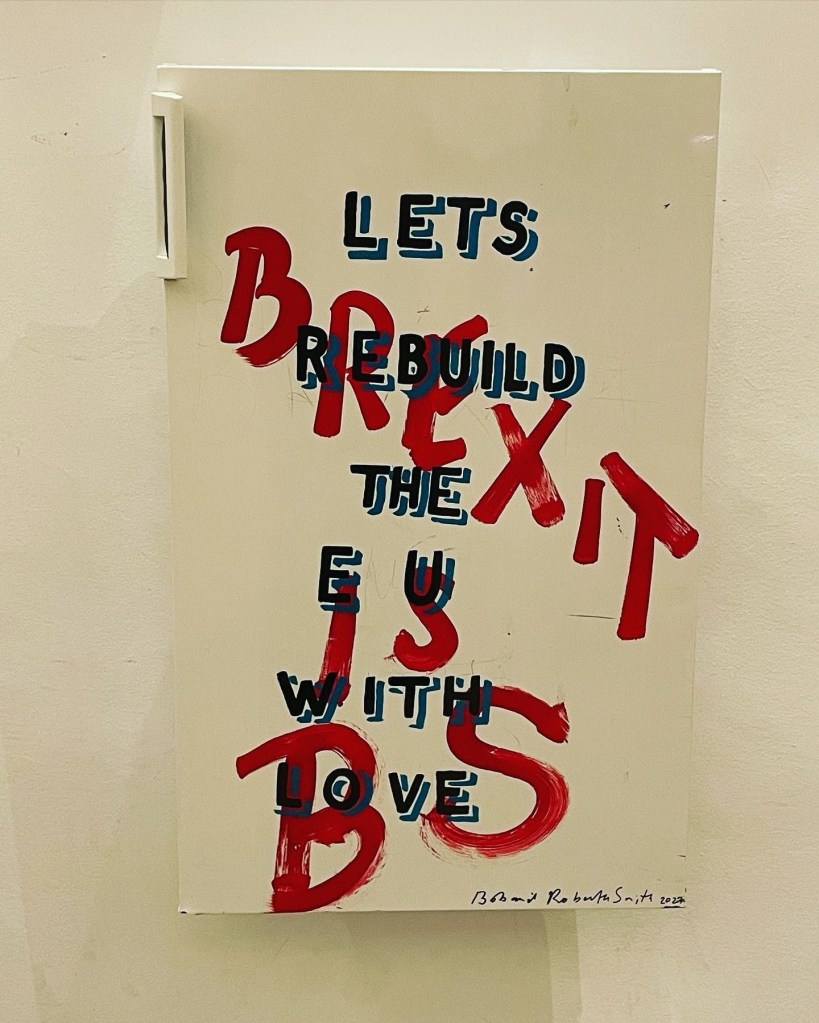

I would say it was hard to get lost if it were not for the half an hour detour we took tumbling down a dark forest following the GPS and ignoring the very clear ‘no trespassing’ sign. It turned out we were right, but the forest spooked us both. As we crossed the barbed wire and our feet became trapped in brambles, I thought of the documentary, Green Border, I recently watched about refugees seeking to cross the Belarussian-Polish frontier at the edge of Europe.

‘You can imagine Dante feeling a little shitty here, eh?’ we remarked.

Finally, arms shredded with brambles we were back on solid ground.

We passed fields of tortured vines that provided a rich supply of local wine and stopped at a vineyard called Fattoria Pagnana to taste the local fare and buy a bottle for tonight’s hosts, a family of six who look after the local church. While much of today consisted of being barked at by aggressive guard dogs, at the winery the two brown dogs approached us tails wagging and tongues lolling out of their mouths, desperate for a touch. Alina like me is an animal lover.

‘Don’t lick my face!’ She squealed.

They licked her face.

At 5pm, our host, Stefano offered to pick us up in the neighbouring village but we were insistent that we would carry on. We resisted the temptation to stay in Rignano sull’Arno for a Palestine solidarity music night and arrived at Pieve a Pitiana at around 8 in the evening with the sun setting behind us.

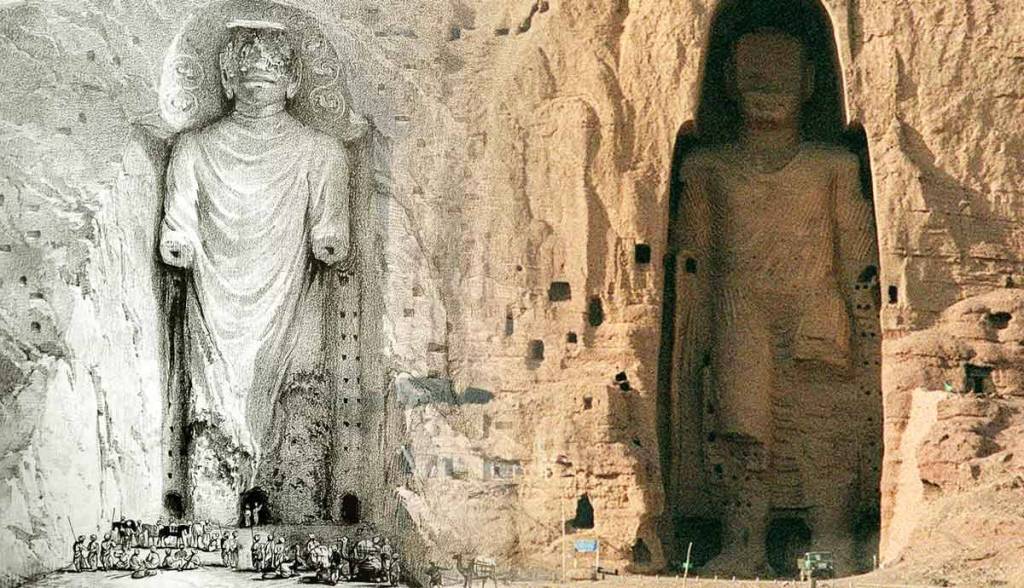

We had both been spooked by getting lost in the forest earlier in the day and now as the sun set, the sun kissed vines metamorphosed into Dante’s wood of suicides.

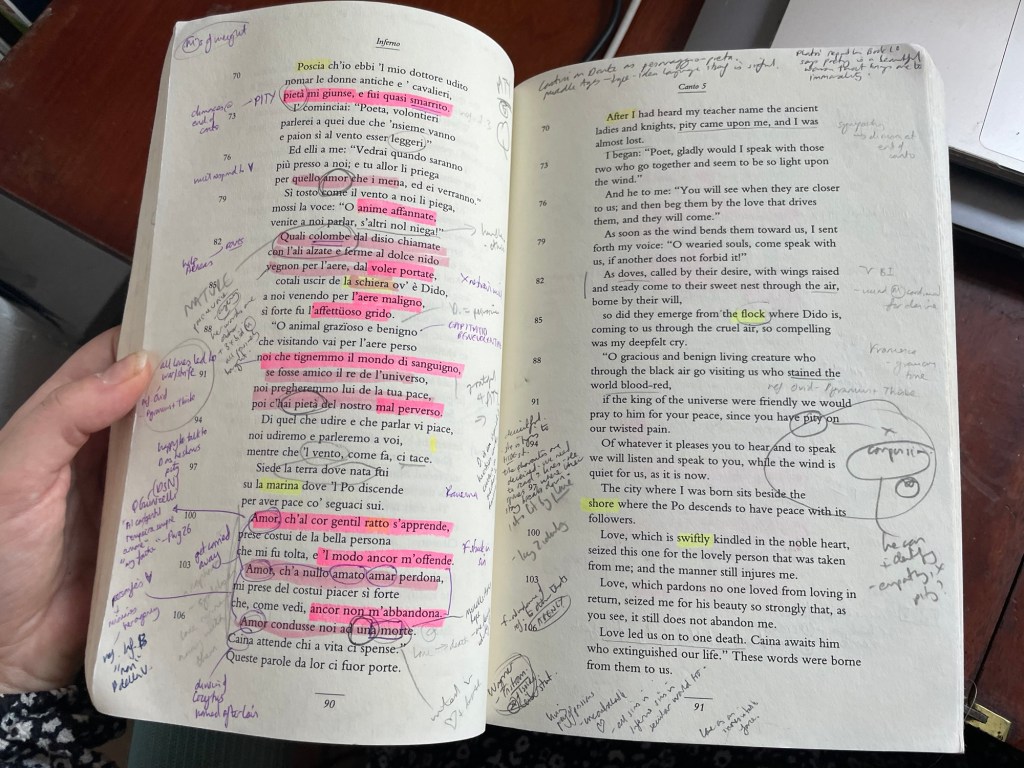

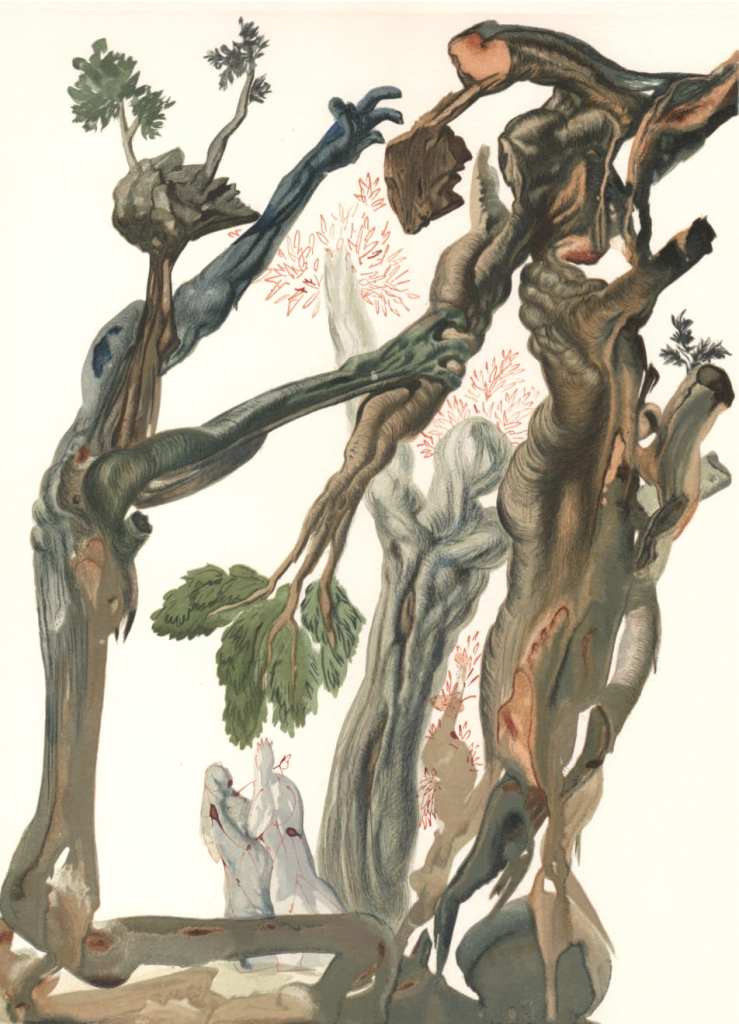

In Canto 13 of Inferno, Dante encounters those who have taken their own lives, following on from Canto 12 where he depicts those who have been violent towards others or their possessions. The canto is heavy with negativity:

‘No green leaves in that forest, only black;

no branches straight and smooth, but knotted, gnarled;

no fruits were there, but briers bearing poison.’

‘Non fronda verde, ma di color fosco;non rami schietti, ma nodosi e ’nvolti;

non pomi v’eran, ma stecchi con tòsco.’

Dante is remarkably kind to the souls, much to Virgil’s chastisement, asking after them and their stories. Virgil encourages him to snap a branch off one of the oaks from which blood drains and the soul within orates. This is how he meets Pier della Vigna, an advisor to Frederick II who killed himself when his reputation was ruined by false rumors. Frederick asks for Dante to heal his reputation on earth, because this is the only part of him that survives outside of Hell. Though encouraged by Virgil to interrogate the tree like an asylum seeker on trial, Dante is so stirred by pity that he says he cannot think of anything more to ask the soul.

Dante describes the tortured woodland as infested with harpies who abuse the souls by ripping off their branches. In an act of symbolic retribution, it is said that when each of the blessed and damned will return with their body from the Last Judgment, those damned for suicide will not re-inhabit their bodies but instead hang them on their branches, both because they denied them in their final act of life and as a reminder of what they denied themselves. Salvador Dalí depicted this starkly in one of his many paintings of the Commedia.

As I mentioned above, Alina and I had spoken over the course of the day frankly about our own very difficult winters. Previous experiences of depression and suicidal thoughts had also weaved their way into our casual conversation, as they had many times before. It felt concrete and somewhat scary to see this fictitious scene brought to life.

We arrived at the church of Pieve a Pitiana to a roaring fire and an equally warm welcome from our host Stefano, his wife Giorgia, Stefano’s mother and their three bubbly kids. Anna, the middle girl-child was excited to practice her English, asking us about our favourite sports, meanwhile the youngest boy was keen to discuss all things Pokémon, later gifting us each a precious Pokémon card (I got Chansey, super power level 80. Get in!)

He had been off school sick and held his arm in a sling made from a shredded blanket.

‘You look like a Roman wearing a toga!’ I commented, at which he giggled. His dimples pitted his face like someone had imprinted it with little olive pips.

We ate a simple meal of pasta al pomodoro with eggs from the three happy free-range hens that were the family pets and aubergine marinated by Stefano’s mother. Stefano and Giorgia talked to us about the 600-year-old house and the church that had even longer foundations. They had met in Peru. Their oldest son Michael was a bit timider but cited to us the first verse of the Divine Comedy after remarking,

‘Wow, you guys are like really, really into Dante!’

I think they were glad to have someone to talk to.

After dinner there followed a private tour of the church where we were able to marvel at the paintings of Ghirlandaio, an early Renaissance painter of the Florentine school noted for his detailed narrative frescoes. One had been stolen, Stefano explained, and a replacement had been installed. He was careful to put on the alarm before we left. Alina said a short prayer.

The house sits beside an NGO that works with local migrant children and the two stories Alina and I shared were strewn with half-finished craft projects and colourful drawings on the walls. Since we both work with refugee children, it was a sight familiar to us both. They marked a stark and stunning contrast with the 14th century stonework which peaked out at points from beneath the pastel plaster.

With full tummies, Alina and I headed to our bunks in the arts room, sleeping beside loo roll easter bunnies and papier mâché masks. A warm shower was most welcome. My inner heels had developed thick blisters while Alina’s little toes looked like they had come down with plague sores.

An open fire kept us warm and dried our soap rinsed socks and knickers as we snuggled into our blankets and rested our weary limbs.

Apparently, I screamed out at one point in the night but this I don’t recall.

Recommended watching (turn on subtitles): Paradise of exiles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-o-lUZq_71E

Recommended watching: Green Border: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt27722543/

Recommended reading: openDemocracy 50.50: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/author/jennifer-allsopp/