I felt immediately at home in Dante’s city of exile, but the most special encounter came in the form of the hospitality of Oliver, our new guide.

I had had the fortune to visit Ravenna on two previous occasions, once on a road trip with my University friends Tor, Martin and Will, and once to give a lecture at the University of Bologna. Ravenna is known as the city of mosaics and, as a mosaic artist myself, I had felt immediately at home in the city. This personal feeling of sanctuary came flooding back as I wondered the streets.

On every corner are little mosaic plaques that depict flowers and announce,

‘Ravenna, city friend of women’.

Though they are never explicitly cited, it is said that the Byzantine mosaics in the church complex in Ravenna (Ravenna has some 200 churches) inspired Dante’s Paradiso which he completed in exile here.

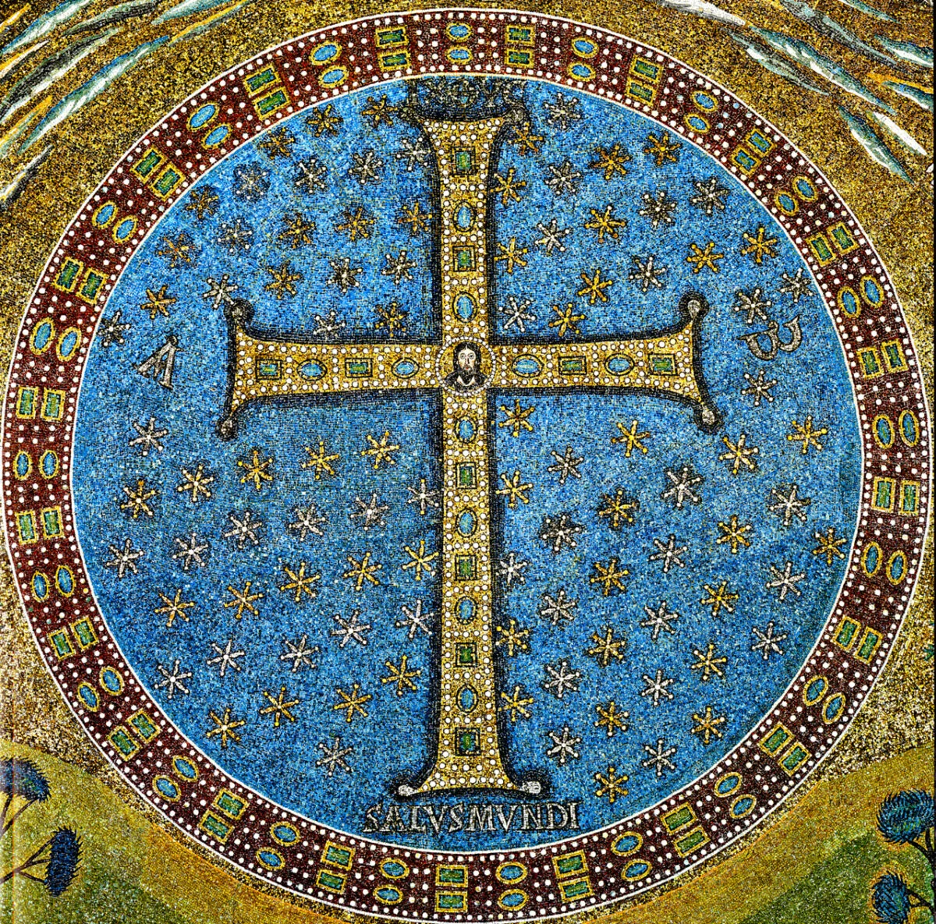

Among the depictions that one can most easily recognize in the Dantean text is the mosaic in the apse of Sant’Apollinare in Classe which contains a sky dotted with 99 golden stars and a gem cross, in the center of which it is possible to see the face of Christ. In the 14th canto of Paradiso, the souls who welcome Dante arrange themselves in the form of a cross, with Christ placed in the centre:

‘As, graced with lesser and with larger lights

between the poles of the world, the Galaxy

gleams so that even sages are perplexed;so, constellated in the depth of Mars,

those rays described the venerable sign

a circle’s quadrants form where they are joined.And here my memory defeats my wit:

Christ’s flaming from that cross was such that I

can find no fit similitude for it.But he who takes his cross and follows Christ

will pardon me again for my omission—

my seeing Christ flash forth undid my force.’

In the 10th canto of Paradiso, meanwhile, Dante encounters a group of blessed souls who surround him and his celestial guide, Beatrice, forming a crown of twelve. A second crown of twelve souls joins them in canto 12, which moves in coordination with the first.

‘And I saw many lights, alive, most bright;

we formed the center, they became a crown,

their voices even sweeter than their splendor.’

It is said that this image could recall the two domes of the Neonian and the Arian baptisteries, where the twelve apostles are depicted in a circle.

It is also possible to imagine that Dante was inspired by the beautiful portrait of the Emperor in the Basilica of San Vitale. Paradiso 6 tells the history of the Roman Empire which Dante viewed as part of the divine plan of Christianity. Justinian has a prominent role. Indeed, the political sixth canto is dedicated to him:

‘Caesar I was and am Justinian,

who, through the will of Primal Love I feel,

removed the vain and needless from the laws.’

The Procession of Virgins and Saints depicted in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo may also have informed his description of the grand procession that heralds the arrival of his Beatrice in the Earthly Paradise.

I left Kelsey to explore the mosaics and caught up with some work during the day before meeting with the current president of the Association of the Cammino di Dante, Oliviero Resta, known to friends as Oliver. We had an appointment outside the tomb of Dante at 5pm.

Oliver is unassuming with his bushy moustache and two pairs of glasses, a contrast to the exuberant personality of Giordano, the founder of the trail, with whom who we had had the honour to spend the previous evening.

His quiet presence is fatherly and reassuring and, once again, I had the feeling that I had met a kindred spirit.

That evening and the next day, Oliver was a host with the most.

The first evening he showed us the house said to be home to Francesca di Rimini who is memorably depicted with her lover, Paulo, in a whirlwind of lust in canto 5 of Inferno. She is accompanied by Helen of Troy and Cleopatra. Her lyrical lament is among one of the most beautiful parts of the Divine Comedy,

‘Love, that releases no beloved from loving,

took hold of me so strongly through his beauty

that, as you see, it has not left me yet.’

I recalled how when I had given my lecture on young refugees in Ravenna, two students in the front row had cried at the love story of Alim who, after being deported to Afghanistan from Leicester at the age of 18, had returned two years later only to find that his beloved had moved on and shacked up with his best friend.

As Dante says,

‘Alas, how many gentle thoughts, how deep a longing,

had led them to the agonizing pass!’

The emotional and relational lives of refugees is a topic long ignored in contemporary scholarship. Dante helps to set the record straight that refugeehood can be a sight of lust and longing.

Oliver took us through the winding streets to see the Basilica which hosted Dante’s funeral. There were signs of the spectacular mosaic floor of the ancient church beneath the foundations which now, quite strikingly, housed a shoal of goldfish.

At 6pm we returned to Dante’s tomb where there takes place, every day, a reading from the Divine Comedy. A crowd of about 50 people had assembled there to hear two women recite a canto from Purgatory. The tomb itself was constructed by Camillo Morigia between 1780 and 1782.

We saw the hole in the wall where Dante’s bones had been hidden by Franciscan monks in 1810 to prevent them being claimed back by Florence. They were found by chance in 1865 and returned.

Dante’s bones were once again buried in a secret place during the Second World Rar to protect them from bombardment by the Nazis. A plaque memorializes this event.

In a pretty market in the square there was an exuberance of flowers and artisanal wares. I bought Kelsey a hand-whittled honey scooper.

‘I’ll think of you when I eat my honey,’ she said.

That night we dined at Passatelli which since 1962 has been serving delicious local fare in a converted old cinema. We ate all local food including passatelli, a thick pasta that resembles a maggot but tastes anything but.

We purchased more roses from Mashalim which we weaved into the doors of Dante’s grave. It was touching to see that the roses we had devoted to him the night before were still there, embellishing the tombsite.

The next day Oliver picked us up in his battered old car that had Dante information boards stored in the backseats that he would put on the trail in the coming days with the help of Giordano’s son, Marcello. Together they maintained every detail of the cammino meticulously.

We passed by the convent where Dante’s daughter had become a nun, taking the name of Beatrice, and visited the lido which had formerly been the port from which Dante had set off on his last perilous diplomatic mission to Venice to negotiate salt taxes.

Though the sea had now retreated some distance from the spot to create a wetland abundant with birdlife, you could imagine the scene. Though he arrived via water he returned from Venice on foot where he caught the malaria that would kill him on the night of the 13th of September, 1321. He was 56 when he died.

Oliver explained that a river used to run through the heart of the city but it had been diverted to prevent flooding. The Ravenna of Dante’s day would have looked familiar but also different.

‘Every pilgrim has his way,’ he said.

Ironically, at 71, Oliver himself isn’t a fan of walking. Some years ago, he’d had a heart attack and had four stents fitted, just like my own father.

Kelsey had a train to catch at 1.40pm which gave us just enough time to check out the Pine forest of Classe, located a few kilometers south of Ravenna, which inspired Dante in his representation of the ‘thick and vibrant’ woods of the terrestrial Paradise, which receives Dante and Virgil along their path in the 28th Canto of Purgatory.

‘A gentle breeze, which did not seem to vary

within itself, was striking at my brow

but with no greater force than a kind wind’s,a wind that made the trembling boughs—they all

bent eagerly—incline in the direction

of morning shadows from the holy mountain;but they were not deflected with such force

as to disturb the little birds upon

the branches in the practice of their arts;for to the leaves, with song, birds welcomed those

first hours of the morning joyously,

and leaves supplied the burden to their rhymes—just like the wind that sounds from branch to branch

along the shore of Classe, through the pines

when Aeolus has set Sirocco loose.’

The forest was full of life. Wild asparagus sprouted in tall stalks and pines shot up like towers. They had been harvested to make boats in the medieval period.

Wild honeysuckle exuded a delicious tangy scent and from an acorn, an oak plant tentatively hazarded a thin thread of life.

‘If you don’t visit a place and touch it with your feet don’t get it,’ said Oliver.

He spoke fondly of his wife, Donatella, who he said was very much at one with nature – somewhat of a tree hugger like me. When she harvested wild strawberries from the forest she asked for permission, he said.

‘Man needs to realize that nature does everything by itself.’

Back on the road, we stopped at a piadina shack that was recognizable from its green and white stripes. I had one with rocket and a local runny cheese called squacquerone. Kelsey and Oliver had ham and hard cheese. I felt Italian, wearing my feather jacket in the midday sun.

Oliver then took us to meet Paulo, another extraordinary man who makes his own ink out of oak parasites, which are rich in tannins, and uses it to write out, by hand, stunning tracts of the Divine Comedy.

This ancient way of making ink requires daily mixing, boiling and the addition of iron and copper to make black from red and green. Gum is added from apricots and peaches to create a substance that is tacky, doesn’t run and sticks to the page.

His work was flawless.

The ink smelt like balsamic vinager and he kept it in a sea shell which he used for his ink pot. He was, he explained, a man of the sea. Mountain scribes use stones with holes in as their ink pots.

He had started on his work with Paradiso since he had been sick at the time and wanted some lightness – Dante’s vivid depiction of Hell was too close to home, he explained. But now he was recovered and halfway through Inferno. It was the second time he had transcribed the Divine Comedy since he was unsatisfied with his first attempt which was rendered in a slightly different, gothic font. He had had to change the font he used because, with age, his hand was not as dexterous.

It took him five to six months to complete a canticle.

On some of the pages you could see the light outline of the lead he had used to draw the lines to guide his careful script. And here and there, he had embellished letters in gold leaf.

Alongside the Divine Comedy he had transcribed the two volumes of Dante’s political tract, Convivio, and the Bible.

After removing the car from his garage so that we could all fit in, he showed us his equipment of an eyeglass, goose feather quill, and a hare’s leg that had been taxidermized and stuffed with cotton. The softness of the hare’s fur gave a particular shine to the embossed parts of the manuscript, he revealed. Each text was written on paper made in the traditional way from papyrus.

The name for someone who handwrites manuscripts is an amanuense.

When we had arrived, Paulo and his wife, Lucia, had been hand making passatelli. Of course they were, they said, it was Easter. They would eat it with prawns and courgettes in a soup, or brodo.

On the walls were family pictures, some of which had come loose from the frame, and a white shaggy dog called Pipo bounded across the room in search of affection. An easter display contained eggs and plastic decorations of rabbits and chicks. From the study two budgerigars were tweeting.

Paulo appeared incredibly humble but also proud of his work.

‘Many normal people do things that are seen by others are titanic,’ explained Oliver.

Then suddenly his wife appeared from the doorway of the garage.

‘The Pope is dead,’ she announced.

‘He met J.D. Vance yesterday,’ said Kelsey, ‘shit I hope he didn’t contract the evil eye.’

I was struck how quickly the conversation moved on back to the books. Paulo was a religious man and the Pope was important, but he was here to show us his own devotional work.

I asked him what his favourite part of the Comedy was,

‘For me,’ he replied, ‘Beatrice is everything.’

He explained that for him calligraphy was a form of meditation that empties his mind.

He read us the last lines of Paradiso and then offered to write it out for Kelsey and I. Yes please, we said. He would entrust it to Oliver to pass forward.

Paulo tucked up the pages he was currently working on in a leather cover as if he were putting to bed a baby.

He used to go into schools to explain his work to the next generation but he fears that the art is being lost. He was teaching a 16 year old called Giovanni and a student at the university had done a thesis on his work.

I thought of my great aunt mary who had taught me how to handmake pillow lace. I’d have to pull out my cushion and bobbins when I got home and see what I could remember.

As we left, we asked if there was anything we could do for Paulo and he simply said ‘remember me.’ This touched me for its similarity to the pleas of the souls in Dante’s afterlife who ask him to remember them when he returns to the earthly realm.

Leave a comment