Today’s walk gave a detailed insight into rural life, while the animals at the farm where we stayed were a delight.

I had met my friend Kelsey in Forlí the evening before, still somewhat shaken after my strange encounter with the dog. To shake it off, we went partying until around 2am.

We must have been the oldest people in the underground club, but we had a blast, dancing and chatting to various Erasmus exchange students. We also met a couple of Moroccan men with whom I spoke Arabic and French. One was a hairdresser from Fez where I have a dear friend from a former home stay called Fatima Zohra. I thought of how unsuccessful I had been at navigating the souk when I stayed with her and felt proud, on the whole, of the navigational abilities I had demonstrated during this trip thus far.

The nardo oil I had purchased at San Pietro a Romena had opened and spilled all over my bag in the night. I was sad to lose it, but at least the canvas now smelt fantastic which was not insignificant given that I had spent over a week sweating into the back of it.

After a slight panic about Kelsey misplacing her wallet, and then her earrings, we checked out of Hotel Lory at 11.30 after a breakfast of pastries, kiwis and bananas. Kelsey pointed out that the reason Italian café paper napkins are so thin and unpliable is because their primary purpose is to be used to hold the food rather than to clean yourself up after it. She demonstrated this with a cream cornetto (no, not the type Pavarotti sung about, but a pastry).

I’d dried my boots on the towel rail and they appeared to have shrunk. After applying two blister plasters to my heels and two smaller elastic plasters to my second toes – which now had blisters at the very end – I had to lever my feet into them with a lot of wriggling and brute force. These were not happy feet. But today had been meant to be a shorter walk of only 15 kilometres. It turned out, of course, to be 22.

‘Do you mind?’ said Kelsey as she strode out into the tentative sunlight, putting on her all-American baseball cap which was a bright lemon colour. She tugged her long brown ponytail through the hole at the back as I laughed,

‘Go for it! Americans on tour.’

Around her neck she wore a wooden necklace of a kingfisher which served as a whistle and, in her ears, she wore studs a friend had made for her out of wood depicting a little hiking backpack and a firepit.

A local pharmacy with an embellished façade had Chinese jars in the window and displays of honey, teas and perfumes. In fact, it was more like an apothecary, but luckily it sold Compeed blister plasters. They really are like a second skin.

Kelsey introduced me to Propoli, an Italian herbal remedy for a scratchy throat made from a resinous mixture that honeybees produce by mixing saliva and beeswax with exudate gathered from tree buds and sap flows, in this case the Mediterranean poplar.

When we stopped for a coffee, we got chatting to a middle-aged man called Alessandro from Bologna who thought nothing of drinking a large glass of prosecco at midday. The café was still displaying Christmas gnomes inside.

When I explained about the cammino, Alessandro began reciting a verse from canto 33 of Inferno, Dante’s famous encounter with the last great charismatic sinner of Inferno: the Sardinian vicar Ugolino who was locked in a tower in Pisa with his children. His sin was to have manipulated his family members in securing and consolidating power over Pisa. This form of exploitation, while taken to the extreme in Ugolino’s case, was systemic in Dante’s dynastic society.

Ugolino narrates to Dante the tortured days of imprisonment in the tower and his death by starvation, a death that takes him only after he has witnessed the deaths by starvation, one by one, of his children and grandchildren. Ugolino is depicted as an absent and terrible father.

‘I did not weep; within, I turned to stone.

They wept; and my poor little Anselm said:

“Father, you look so . . . What is wrong with you?”

Therefore I shed no tears and did not answer.’

Dante insists on the innocence of youth, saying of the children, ‘their youth made them innocent’, seeming to imply that Ugolino’s sins should not have been visited upon his descendants.

I reflected on the many young male Albanians with whom I’ve worked who have fled blood feuds of familial descent, a phenomenon that is largely ignored by the UK government in asylum decisions.

Though the text is ambiguous, in a dramatic crescendo it seems to imply that Ugolino ate one of the bodies of his children who offered himself up to him so that he might survive a little longer:

‘As soon as a thin ray had made its way

into that sorry prison, and I saw,

reflected in four faces, my own gaze,out of my grief, I bit at both my hands;

and they, who thought I’d done that out of hunger,

immediately rose and told me: “Father,it would be far less painful for us if

you ate of us; for you clothed us in this

sad flesh—it is for you to strip it off.”Then I grew calm, to keep them from more sadness;

through that day and the next, we all were silent;

O hard earth, why did you not open up?But after we had reached the fourth day, Gaddo,

throwing himself, outstretched, down at my feet,

implored me: “Father, why do you not help me?”And there he died; and just as you see me,

I saw the other three fall one by one

between the fifth day and the sixth; at which,now blind, I started groping over each;

and after they were dead, I called them for

two days; then fasting had more force than grief.’

This is a famous passage which Alessandro must have studied at school.

He offered to buy us more coffee, but we made our way to the Duomo of Santa Croce where Kelsey had attended mass the evening before. She took her cap off as we entered and made a cross.

The cathedral contained a spectacular array of marble and, to the left, the Madonna del Fuoco, the Fire Madonna, a painting of the Virgin Mary with Jesus. An information plaque and mural informed us that the artwork had hung in a school until 1425 when it miraculously survived a fire. The Fire Madonna is now considered the protector of the city.

Though the Piazza Dante Alighieri was a bit disappointing – an urban rectangle of stray cats and pigeons with a war memorial – a plaque on the wall of the surrounding street said something of the time the poet had spent in exile in Forlí: ‘here, the house of the Ordelaffi family welcomed Dante Alighieri’.

The cross at the alter had been covered by a large maroon cloth because it was Good Friday. They would unveil it again on Sunday to mark Easter, when Jesus came back to life.

A man with brown skin and worn shoes showed us the screen of his iPhone where there was written a request for money in multiple languages.

The market was in full swing outside the church, including clothes, shoes and fresh vegetable stalls from local farmers. We passed by a tiny rusting Fiat red panda car. A lady in a leopard coat with matching trousers and purse cycled by. A sausage dog came waddling down the street.

We had a leisurely lunch at a restaurant called Zio Bio 100% natura in Piazza Dante Alighieri. It consisted of aubergine parmigiana, a delicious crecione (the typical specialty of Romagna cuisine I had first tried yesterday) and fennel salad.

Delicious doesn’t come close to it.

Today’s stretch of the cammino began with passing through the city gates of Forlí. From there we proceeded to a river where we had to army roll under a metal fence that blocked the path with a no entry sign which, by now, I’d learnt to ignore.

Like the doors of Dante’s Hell, it seemed to say,

THROUGH ME THE WAY INTO THE SUFFERING CITY,

THROUGH ME THE WAY TO THE ETERNAL PAIN,

THROUGH ME THE WAY THAT RUNS AMONG THE LOST.JUSTICE URGED ON MY HIGH ARTIFICER;

MY MAKER WAS DIVINE AUTHORITY,

THE HIGHEST WISDOM, AND THE PRIMAL LOVE.BEFORE ME NOTHING BUT ETERNAL THINGS

WERE MADE, AND I ENDURE ETERNALLY.

ABANDON EVERY HOPE, WHO ENTER HERE.These words—their aspect was obscure—I read

inscribed above a gateway

Though we could see the mountains peeking in the distance, the route all day today was totally flat to the point that I almost missed the hills.

What I didn’t miss was the continued surplus of tacky mud.

As we crossed under a bridge, our feet were submerged by the molten riverbank. Further up, the terrain was cracked from where the river had recently been higher due to excessive rainfall and washed away the bank. Two men on bicycles also sought to navigate it.

There was a light breeze and the clouds hung low in the sky.

We passed through another ‘do not pass’ sign and observed a crane doing work on the other bank of the river.

After about an hour, the road became a raised mount between two ditches on which we continued nearly all the way to our final destination. The track was perfect for two people to walk side-by-side, which we did. It was riddled with ant mounds, beetles and seeds the shape of hearts (Kelsey’s interpretation) or pig snouts (mine).

‘That’s the biggest worm I’ve ever seen!’ Kelsey exclaimed.

Plastic nets had been placed over fruit trees to protect them from intruders – a white wedding veil here, a black funeral mantilla there. Kelsey whose work focusses on reducing plastic waste in fishing, pointed out the damage of such farming innovations.

We passed several farmers who were maintaining their fields and pretty country houses with large gardens. One had a rectangular swimming pool like a humungous bathtub. Another had a trampoline.

It felt somewhat voyeuristic to be staring down at this from on high. I thought of a backwater tour I had taken on a boat in Kerala and how awkward I had found the experience of staring into other people’s private yards and private lives.

The flat, single-track walk became a little tedious with the hours and I was grateful for Kelsey’s company. Though I was also sad that she had missed the more spectacular parts of the cammino.

By midafternoon, the wind had dropped and it was quite humid. A bird had become caught in one of the farming nets. As it futilely flapped upwards, we contemplated descending to try to rescue it but the bank was too steep. I thought of Ugolino in his tower and wondered if it would slowly starve to death. This is the price of our fresh nectarines, I thought.

As we walked, Kelsey was inspired by the agricultural landscape to tell me about her childhood. Growing up in Southern California in a rural town she could relate to the scenery which also reminded me of a Steinbeck novel.

A Bobcat tractor made her recall her twin brother Carl doing wheelies on theirs, while the waft of manure reminded her of playing in horse dung piles as a girl.

Red bugs burrowed into seed shells and a slug slowly made its way across the path.

A man in a smart bright blue coat was collecting dandelions for his rabbits. He scratched his back with his sickle dexterously.

There were horses and cockerels in the pretty farmsteads and gaggles of happy geese.

Kelsey picked up rocks to examine them as we walked. She also collected stray pieces of plastic that had been discarded on the road.

We passed an abandoned house which was framed by a caravan and a water tower.

Around 5pm, we stopped to take off a layer in the evening sun, sitting on the verge and putting our feet together and pumping them in a grounding stretch. I used to do this with my brother as a child when we were bored. We called it the ‘thinking game’. In a play on words, Kelsey called it ‘sole heal-ing’.

Our shadows merged together as we carried on beneath the crepuscular rays.

We passed by sprigs of elephant garlic which has healing properties and grass that looked like leeks. A hare leaped across a field, pumping its hind legs in tall arches like a water sprinkler.

I reassured Kelsey not to worry too much about ticks or rattle snakes which had killed many of her cats and dogs as a child.

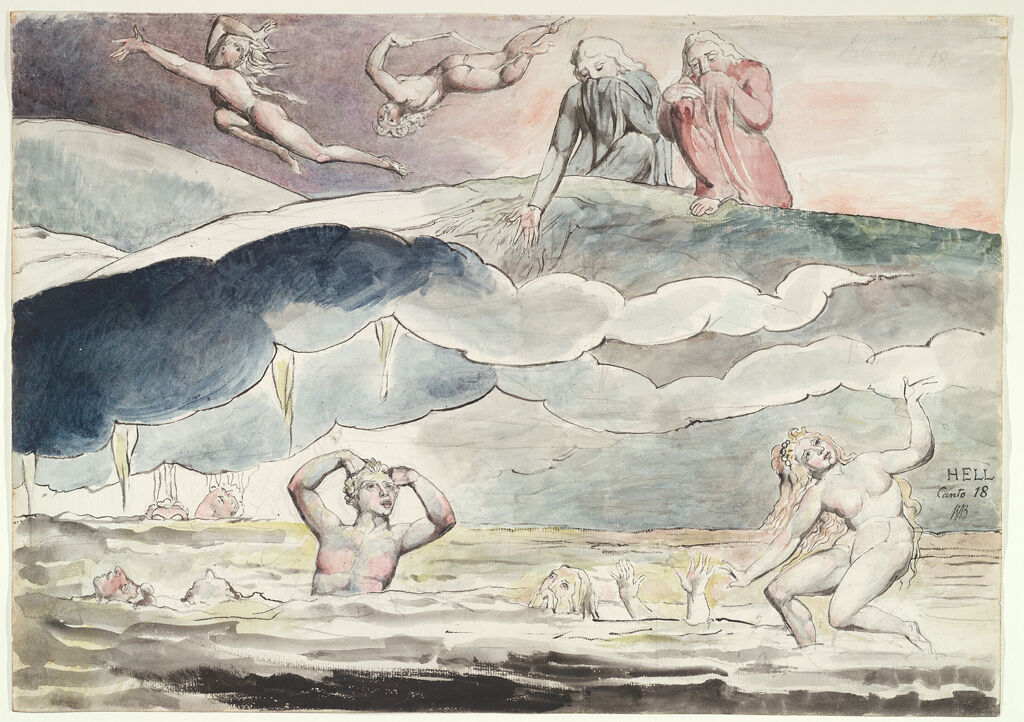

Nearing the farm stay we had booked for the night, Fattoria Chiocce della Romagnole, we took a shortcut through an apricot farm. We passed by a muddy ditch, into which I promptly fell and soaked my left foot, and a stinky swamp. I was reminded of the eighth pit of the Malebolge (‘evil pockets’) that constitute, in a wheel shape connected by bridges, Dante’s eighth circle of Hell. These ditches, or ‘pockets’ are used to punish various sins of fraud. One example is the second bolgia, where flatterers are submerged in excrement.

We arrived at our accommodation around 6.30pm to a warm welcome from our host Rossella and from a sturdy-looking man who was mowing the lawn.

Everywhere there were animals.

Chickens with glossy coats of different varieties pecked at the ground; geese, both white and grey, waddled around on their neon orange feet; turkeys waved their wrinkled necks; guinea pigs nibbled on hay; sheep baad from a field behind the farmhouse; and two parrots, one red, one a grey African, spoke out to us. The guard dogs barked into the evening air. But best of all, four donkeys merrily wondered around the garden nibbling on the grass.

Kelsey is a huge animal lover.

As we walked, she had told me about a donkey she had owned as a child called Sweet Pea, on whom she would ride around selling girl scout cookies. Once, he had bitten off the button from her brother’s jacket. He was choking, so Kelsey had had to hold open his mouth while Carl put his hand down her throat to retrieve it.

‘She was such a good girl.’

When Sweet Pea died, they had used a tractor to dig her grave, only for it to fall on top of her. All of the neighbours had pitched in to tie ropes to rescue the tractor from the pit. In this landscape, I could picture all too well her rural childhood and took great pleasure in seeing her nuzzle the donkeys and kiss them on the nose.

The most lightly coloured one, Mais, Rossella explained to us, had become famous when, during a period of bad flooding that cut off the roads, he had walked three kilometers to safety with the help of the emergency services alongside his two girlfriends. In a play on words with his name, he became a symbol of the region’s resilience:

‘la Romagna non molla Mai(s)‘ – Romagna never gives up!’

Two men, Marco and Francesco, were also staying at the farm having left from Ravenna yesterday to do the Cammino in the Florence direction. Helpfully for other hikers, they are recording their walk on the app, Komoot.

‘Oh, so you’re Jenny from the blog!’ they exclaimed.

In our room, two kittens, one with a black patch on his eye and spot on his face, the other grey, brown and white, played on our bed, jumping to catch iPhone cables and sniffing every item as we unpacked. The grey one purred like a motorbike.

‘It must be a lot of work running this place,’ I commented to Rossella as we warmed up our dinner of artichoke pie.

‘It’s not work, it’s pleasure’ came her reply.

She was cradling, in her arms, a black and white skunk called Margarita.

Leave a comment