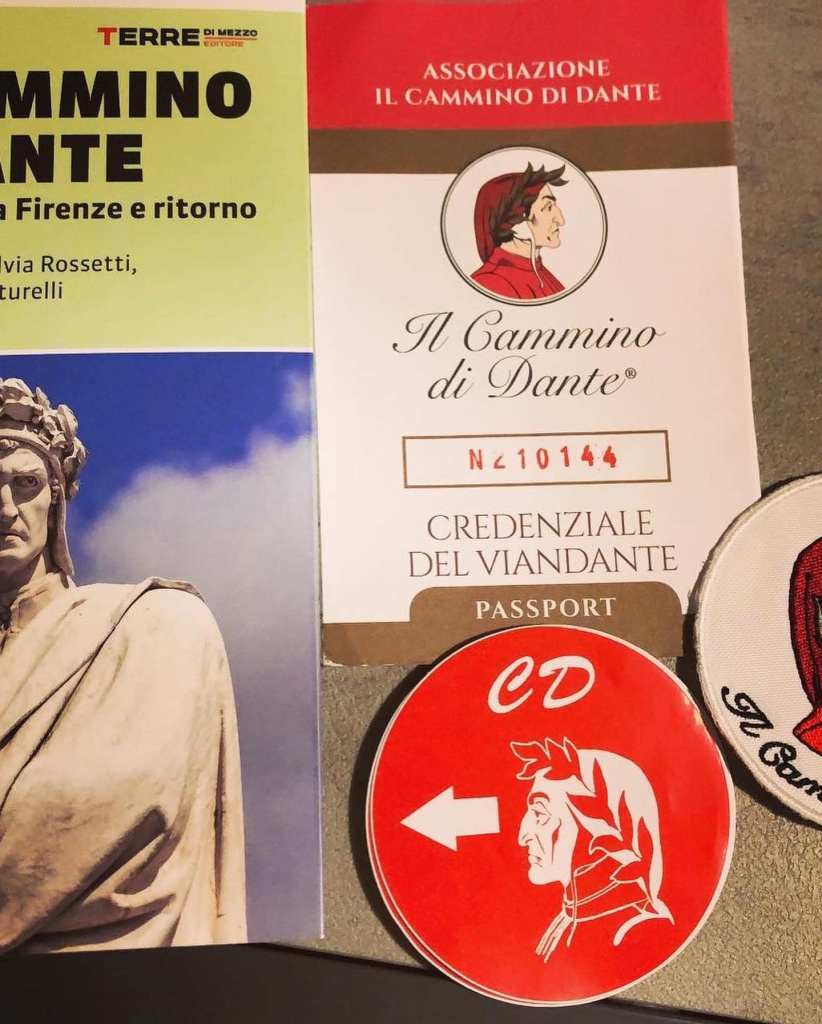

My Dante passport has arrived but I won’t be using it. Here’s why.

My map for the cammino di Dante arrived in the mail as promised this week and it was accompanied by a passport. I was number 20250033, the thirty-third person to attempt the pilgrimage this year, perhaps. This is not uncommon in contemporary walking trails – you get a ledger where you can lodge your progress, that feels good, like accumulating stamps in a passport. I’ve been there. In my youth I took huge pleasure in seeing my battered red passport bulk up with stamps and timbres as I crossed the world’s many borders with the ease of an enthusiastic young white British woman. I fancied myself a Gertrude Bell in the making.

I recall waiting at the Syrian-Lebanon border for hours to be gratified with a little fir tree bestowed in the form of a pasted stamp – passage granted. That night I was travelling with an Irish fellow Arabic student, and we spent all our money on food and crashed out with a bottle of red wine on the Beirut beach. We woke bellies satiated but our skin covered in bites from sand flies.

Crossing borders used to be a fun part of travel for me, now it gives me a deep sense of unease as I am aware of the many reasons some people and not others can cross.

Dante’s Hell is a landscape strewn with borders. No souls can travel beyond the place assigned to them and Dante’s passage is often challenged, and it is up to Virgil, his guide, to defend him and lobby for his right to pass. He’s tricked, devils send them the wrong way and Dante stumbles and faulters at the threshold of many the next descent. Crossing the River Styx he faints from the stress of the crossing, something contemporary ‘boat refugees’ might all too readily relate to.

As I set off on Sunday afternoon in the rain to do a 3-hour training hike, I thought about the reasons I am embarking on this pilgrimage – to reflect on some 20 years working with the world’s refugees and try to find some hope in a dark time for people on the move and those who care about them. I thought of my passport back home – blue now (thanks Brexit!) and how it would be stamped when I arrived in Italy some two weeks from now. I thought of the world’s 43.4 million refugees and 4.4. million stateless people.

As a child this was unimaginable to me. I was an impassioned member of the European Youth Parliament and in my teens I would spend my Spring and Summer holidays happily flitting across Europe to visit my Italian exchange family in Turin and my adopted French family in Montpellier. Later I would work in both countries, as was my right as a British and then European citizen.

I’d met both families through teachers as part of language exchanges that used to be the norm. My own failing state school, Lord Grey, was made a languages academy as part of a government programme at the time and I was all too eager to gobble up the opportunities this opened up to me.

I arrived in Montpellier nervous but excited at the age of 14. I carried myself well, my only mistake being to lie that I enjoyed the Roquefort salad with such enthusiasm that it would be served from then on a regular basis, much to my chagrin (I now don’t mind it in a quiche!)

My host sister Marie was a gymnast, sarcastic and smart as a whip. We quickly developed a relationship like sisters. We’d bicker and share make-up and make up.

When I was at University, and came to Montpellier to work as a language assistant in a high school through ERASMUS we were roommates. She was studying for her medical exams and I leant her my Dictaphone. I would regularly hear the repetition of words as she bathed in our common bathroom – an-o-rex-i-a ner-vo-sa – from the Greek, an-orexis – without appetite. She chain-smoked her way through the brutal first year and passed with flying colours and today she works as a psychiatrist. An-orexis. The words still repeat in my mind.

In Turin I would lodge with an Italian family who couldn’t have made me feel more welcome. The mum would grate parmesan cheese on the cat’s kibble and hide ham beneath my salad (‘to be vegetarian is to be sick!’ Mamma Colto would insist). Together we’d read Dante’s sonnets in the kitchen as she prepared a feast for the family of four – steak for the two strapping young men and pasta pesto for me. She was ever so smart Mamma Coltro but she’d made the mistake of getting divorced and so she felt it was her penance to serve the family now above all else. It seemed so unfair at church on Sundays when she wasn’t allowed to take mass. I would try to sing along, articulating the phonetic sounds of words I was yet to understand and marveling at the glorious frescos in the pretty little local church. Later, when I went off to India on my own at the age of 18 Mamma Coltro was horrified. I wrote about her and the other mothers I accumulated on my travels in a poem, All My Mothers, which I include at the end of this post. It’s a suitable tribute as Mother’s Day approaches.

It’s sad to me that British kids today will never know that unfettered movement throughout the European Union. Meanwhile because of health and safety, it seems schools are less likely to offer exchange programmes to their students. They’re barring us in.

It was my late Italian teacher, Andi Oakley, who first introduced me to Dante when I was 15 and my art teacher, Adrien Lee, who set me off to Florence for an artistic immersion (he now works as a ghost buster in the States). With a heavily annotated map, I dragged my mum around the Uffizi – she was wearing high heels to fit in – and I eagerly took her to the various churches to marvel at the frescos of Masaccio, Giotto and Cimbue. She was an enthusiastic student, as was I. Dante writes about Giotto surpassing Cimabue.

To travel is to pursue something new and never done before, to ‘trapassar del segno’ – to push beyond the limits. But Dante warns us that as travelers we have to be humble too. See Ulysses’ last voyage. How in canto 26 of Inferno he writhes as he speaks from a fraudulent tongue of fire urging his men to push on past the straits of Gibraltar to discover the new world despite the great risks. ‘You were not made to live like beasts,’ he urges them, ‘but to follow virtue and knowledge!’ The sinking of the ship was rendered starkly by one of my Reading Dante with Refugees students, Mohammed, from Iraqi Kurdistan (see last post). He could relate, he’d been a rare survivor of a shipwreck upon trying to reach my precious Europe without a passport.

Most of the people I have worked with do not have a passport, or rather their passport is worth little of value to them once they have become refugees or worse, stateless. Dante too likely found himself in the position of being a refugee. Though nation states were yet to be established, associated with the rise of the modern ‘Westphalian system’, following the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, he was cast out of his city state without documentation. King Henry V of England is credited with having invented what some consider the first British passport in the modern sense, as a means of helping his subjects prove who they were in foreign lands. The earliest reference to these documents is found in a 1414 Act of Parliament. Dante was exiled in 1302.

A refugee was and remains someone who is unwilling or unable to avail themselves of the protection of their host state because of a well-founded fear of persecution due to race, nationality, religion, political opinion or membership of a particular social group. For people like Mohammed, a passport is a goal not a privilege. As such, as I embark on my Dante cammino two weeks from now I won’t be stamping the passport at the various stops in recognition of the millions of people who have no such document and must travel clandestinely through Europe and Italy. Perhaps I will miss out on discounts at Dante attractions en route but, alas, once I have cleared passport control and entered the country I will be an undocumented Dante pilgrim.

Recommended listening, Passports Please by Katy Long, BBC: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08nrzpr

Recommended reading, The Invention of the Passport, John Torpey: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/invention-of-the-passport/92242092DFC0BEEDD5486AA7B858F91B

All My Mothers

I collected mothers like dolls.

Beads on a necklace

A bracelet of charms.

The Italian one, Catholic, hid

porchetta beneath the lettuce

for to be vegetarian was to be sick.

You taught me how to haggle in Porta Palazzo

How to use the horn

Stared in horror at the photos from my travels and

sent money to the children.

‘Why would your mother let you go?’, you sighed.

We recited sonnets to each other,

Petrarch and Dante,

as you grated parmesan onto the cat’s dinner

wiped your chapped hands on your apron and

cooked another steak for your sons.

I made a crumble for my colleagues, remember,

but you confiscated all the Tupperware and

made a perfect pie.

‘Take that instead’ was your command.

‘Ma che crumble!’

You were distinctly unimpressed

with the food I brought to the family table

but not the conversation.

You said you’d never had a daughter

You’d always dreamed of travelling and that

once, in your youth, you’d been to China.

The weeks ran into months

The snow in the fields became fresh cherries and apricots

We drove down to the city through the smog,

surrounded by mountains like an open jaw.

‘Oh no, it wouldn’t do for my sons to have a girl like you’, you said

when we visited Vesuvius together.

You’d made us lunches for the plane.

The French one, with strong legs hiking up Pic Saint-Loup,

took me to see abbeys, chateaux and aqueducts.

We ate rum cakes from the market and you

showed me your plans to restore the Tuileries.

Lectures on the history of art

Ballet at the opera house

Sipping on the season’s first Beaujolais as we

discussed the novels of Chamoiseau and Maryse Condé.

You kept me reading through the sadness,

And playfully teased my father for his long hair.

‘Ah, les hommes…’

I’d never really laughed at him before.

It felt transgressive

Empowering

Like I’d crossed a border

and when my colleague assaulted me outside the house you defended me like a daughter.

We toasted my brother’s engagement with champagne

and I made a tarte au citron to celebrate.

It wasn’t half bad

but I’d spilt the lemon and corroded my carelessness

into your marble table.

You were never cross,

just with the parrot when he nipped your heels.

I never did sleep with your son

though we watched Singing in the Rain in his Paris apartment as the

heaven’s opened and fell outside over the cemetery.

You smiled at my wedding like a mother of the bride

floating across the meadow with a glass of wine,

your movements mellifluous, luxuriant, fun.

‘If you want to be an artist you must wear nice fabrics’, you once said.

The Cuban one, on the make,

Mojitos and late nights on the Malecón.

My Spanish was shaped by the men who’d broken, to you,

their promises.

Love songs and tears.

Ice cream and popcorn.

Dancing with the neighbours on the roof until well into the morning

and the sun came up like a warning

and the cars began to belch past in the street.

Remember, I went scuba diving with the friend of your secret lover?

We dove deep

Swam into a grotto where he took my breath away.

We were thirty metres down when he removed my regulator.

Panic in my eyes he

kissed me

left the

gas

on

so

that

bubbles

formed then

led me up, up above the cave to watch them

filter through the rocks into the crystal sea.

And there were fish

And it was all so blue against the

coral which was gilded like an altar,

and sun rays pierced the fragile water.

I’d never seen anything quite so beautiful

nor been so vulnerable.

Meanwhile you were making out in your lover’s office.

‘Would he ever leave his wife?’ you asked me again and again.

You told me it all.

God, it was all so romantic, wasn’t it?

On the way back we both swooned.

You were fifty and I was eighteen.

The Indian one, licking ghee off worn fingers,

always slightly flushed,

Your hair clotted to your forehead

for the sweat under your veil.

You were almost always in the kitchen.

I can still smell the mustard seeds.

The roti that made your palms strong.

We never exchanged a word in English

Our language was cooking and touch.

I made you beans on toast, remember,

and you couldn’t stop laughing.

You almost fell over you were so immersed in the sensation

Then the men entered and you blushed.

Your children tied bracelets to my wrists and called me behen.

When your daughter married I stood beside her

She wasn’t meant to smile but she said because of me she did.

She had your smile,

said she’d ‘bloody kill me’.

I taught her that.

Did she ever tell you that she tried to pierce my nose

when I was prostrate, waiting for my eyes to heal?

‘Four types of drops, on the hour, every hour’, the doctor had said.

‘You’ll need someone to care for you.’

Years later, my mother-in-law couldn’t believe

I’d not come home.

The Moroccan one, strawberry jam: tuut!

You showed me how to skin a calf,

also unconvinced by my being vegetarian.

You whispered saha beneath your breath as I washed myself.

Next to your house

in the Old Medina

you scrubbed my back with black soap.

I was aghast at the shame of the

skin

that

speckled

the

water.

Grey and oiled,

You grated it into your palms.

Your breasts were swaying to

the slosh of buckets

I’d never seen women like that before.

Through the steam they were laughing as their

naked children splashed one another

and their mothers combed their hair and picked their ears and

made them clean.

Yes, growing up I played with mothers like dolls.

New languages, lexicons

Moments.

Leave a comment